Examining how the author Richard Nicklin Hall (1853-1914) justified his thesis that Zimbabwe’s gold mines were dug in ancient times by foreign miners

Introduction

Hall’s thesis that the gold mines found throughout then Southern Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe, were ancient and dug by foreign miners (Sabaeo-Arabians, Phoenicians and Arabs)[1] is laid out in the book The Ancient Ruins of Rhodesia (Monomotapae imperium) that he co-authored with W.G. Neal and published in 1904 and was to become the standard work on this subject.

This article concentrates on the gold mines only and Hall’s defence of his ancient and foreign thesis in Chapters 1-3 of Prehistoric Rhodesia. The article does not attempt to refute any of Hall’s statements; this has already been done by many archaeologists such as Summers, Garlake, Phimister, Mitchell and Begg, etc. What it sets out to do is present Hall’s statements in a more concise and digestible way for the modern reader, but without endorsing them in any way as the bulk of Hall’s conclusions were completely incorrect and based on his biased racial views. Many of the Portuguese writer’s statements that he quotes are probably true, or were in the sixteenth / seventeenth century, and used by Hall to bolster his argument that Professor David Randall-MacIver’s theories were incorrect. However, modern archaeological research has proved that the conclusions that Hall came to based on the writings and his research were incorrect; the gold mining was not carried out in ancient times by foreign miners and in fact, Randall-MacIver’s theory that they were more recent, and that the gold mining was carried out by local people, is correct.

The original text as taken from Hall was 44 pages along and I have edited it down to its current 20 pages whilst trying to retain his original context. Sections edited I have marked [**] terminology and phrases used by Hall that I consider offensive I have removed from the text.

W.G. Neal [2] and the Rhodesia Ancient Ruins Ltd

Frederick Burnham, who survived the fate of Allan Wilson and his Shangani Patrol (See the article James Dawson’s account of finding the remains of Allan Wilson and his patrol under Matabeleland North on the website www.zimfieldguide.com) writes in his biography Scouting on Two Continents, “My contract with Smithsonian scientists exploring among the cliff dwellings of our own Southwest, as well as my search for lost mines in Mexico during my boyhood, had always kept me keenly alive to the tales of African natives about great huts of stone and deep holes in the rocks made by people who burned the rocks with fire. This led me to the finding of the Dhlo-Dhlo ruins[3] and their gold treasure and the granting to me by Cecil Rhodes of the right for their further exploration. Some of my enthusiastic friends formed a company and bought my interests for a few thousand pounds, all of which is set out in a most entertaining manner in a large book written by Hall and Johnson, who took over the exploration.”[4]

Burnham doesn’t give details, but in 1894 he recovered 641 ounces of “gold inlaid work and gold ornaments” at Danangombe (See the article Danangombe Monument (formerly Dhlo-Dhlo Ruins) under Matabeleland South on the website www.zimfieldguide.com) some of which he gave to Cecil Rhodes; the rest he kept himself, or sold as bullion.[5] Soon after W.G. Neal and G. Johnson found five buried skeletons in the small Mundie ruin, some 110 km south of Danangombe, with 208 oz of necklaces, bangles and bracelets, which realised £3,000. The two prospectors established a company, Rhodesia Ancient Ruins Ltd and in September 1895 the British South Africa Company (BSACo) granted the company, “the exclusive right to explore and work for treasure” in several ruins in Matabeleland and, “the first right to work further ruins.”

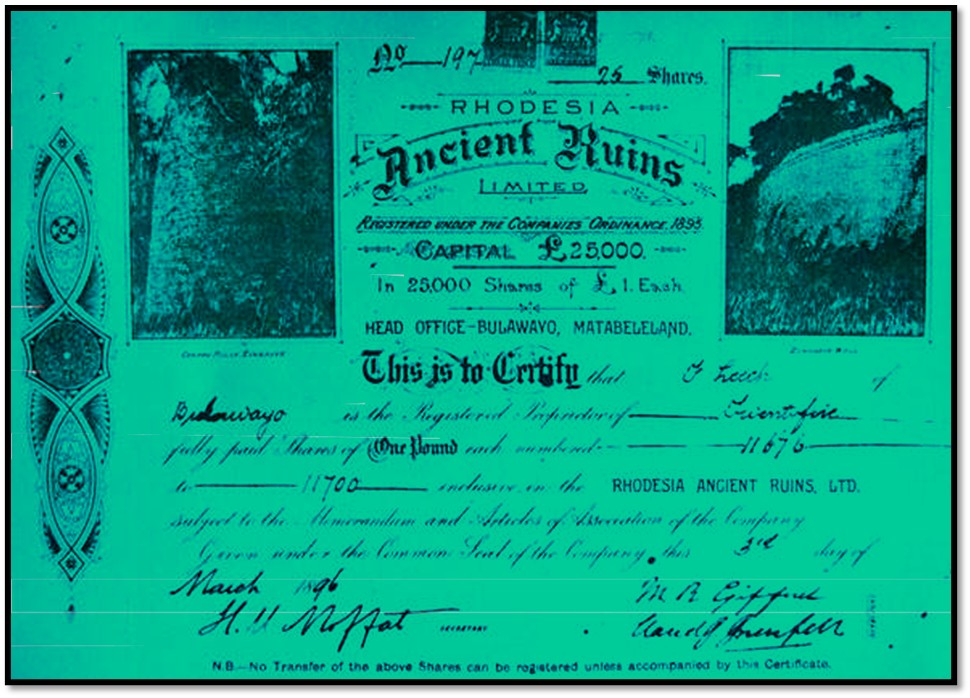

Shareholder certificate for the Rhodesia Ancient Ruins Limited Company

Shareholder certificate for the Rhodesia Ancient Ruins Limited Company

Initial shareholders were Maurice Gifford, Jefferson Clark, Tom Peachy, W.G. Neal, George Johnson and Frank Leech. Neal and Johnson agreed to do the actual exploration and digging. In return for the concession, the BSACo would have 20 per cent of all finds and that “Mr Rhodes on behalf of the BSACo [would have] the first right of purchasing any discoveries.” Great Zimbabwe was excluded from the company’s activities. Following the Matabele (Umvukela) and Mashona (First Chimurenga) rebellions, another fifty ruins were dug up from September 1897 to May 1900 when the company ceased operations. However, apart from Chumnungwa and M’Telegewa Ruins, where a total of 178 ounces of gold were recovered, the company records reveal only small amounts of gold were found.

But growing public awareness of the irreparable damage the company was doing to prehistoric remains put a stop to its operations. At a meeting of the Rhodesia Scientific Association in August 1900 a letter from Neal was read that included a sketch of a copper ingot from the Mpateni ruins, and at the October meeting a number of artefacts were exhibited by Neal including a portion of a large crucible with a button of gold in it, gold leg bangles from a burial site, many gold beads, pieces of pottery and an "ancient gaming table.[6]"

Perhaps to atone for the damage resulting from his treasure hunting Neal made all their Rhodesia Ancient Ruins Ltd company records available to R.N. Hall* and as a co-author presented a paper, "Architectural Construction of Ancient Ruins in Rhodesia", before the Rhodesia Scientific Association in February 1901, published in the Association's Proceedings (Vol. 2, pp. 5-28). This paper was expanded greatly into the book, The Ancient Ruins of Rhodesia (Monomotapae Imperium)

Dr Randall-MacIver conclusions following his 1905-6 excavations at Great Zimbabwe

Dr David Randall-MacIver carried out excavations at Great Zimbabwe and stated in his book Medieval Rhodesia that all the archaeological evidence from the site was that it was built by African people within the comparative recent past.[7] His conclusions were read in two papers at Bulawayo and the Royal Geographical Society and also in his book, Mediaeval Rhodesia published in 1906, dating the ruins and gold mines to not before the fourteenth century, a highly controversial view at the time that ran counter to popular opinion in Southern Rhodesia.

In contrast Randall-MacIver’s conclusions regarding the origin and age of the Rhodesian gold mines and buildings was that they were, "not earlier than some time in the eleventh century A.D." and that the buildings were the work of "a negroid or negro race of African stock" and "characteristically African" and that the archaeological finds, except for the imported items were also "characteristically African" and "not more than a few centuries old."[8]

R.N. Hall’s reply in The Ancient Ruins of Rhodesia

In the 487 pages of Prehistoric Rhodesia, published in 1909, Hall gives his reply, “But on the question of the actual ruins and rock mines, I have always consistently held that both the oldest types of ruins, and especially the rock mines, belong to some period of antiquity, and, further, that these did not originate with the unaided Bantu.”

“Therefore, I fail to discover anything in what Professor-Randall-MacIver has written to shake those conclusions. As I stated, now some seven years ago, and have repeatedly demonstrated on many occasions since, there are ruins belonging to some remote prehistoric times — such as those of the Zimbabwe type, also those of mediaeval and post-mediaeval times, and also those stone rampart walls of crude construction for which late MaKaranga must be held responsible. The same applies to the mines, which show varying degrees of culture, the oldest displaying the greatest skill in mining.”

Hall attempts to classify the gold mines into periods

“…there were three ‘periods’ in Rhodesia, and that in each period the type of building decidedly varies, each type building having its own individualised and specialised form of construction and yielding respectively a class of relics only found in such particular type of building. The periods were:

( 1) the Prehistoric period of the rock mines, the Zimbabwe type of building with its ceremonial practices, and the very general use of chaste gold ornaments, all demonstrating culture in its most perfected form,

( 2) the Historic period of the river sand-washing for gold, with a crude form of building and a marked decadence in the arts; brass, iron, and copper ornaments only being in use,

( 3) a late period, with MaKaranga stone rampart walls, extending down to the last fifty years.

Hall attempts to bolster his own thesis by association with Theodore Bent’s work in The Ruined Cities of Mashonaland: Being a Record of Excavation and Exploration in 1891

Hall writes, “…One [of the] striking and most gratifying features of the controversy which lately raged round the grey-lichened walls of the Zimbabwe Temple is the widely increasing appreciation in which the work of Mr Bent is held. His grasp of ethnological matters in South Africa places him high in the estimation of all authorities on the Bantu. His archaeological work at Zimbabwe stands witness to most careful, exact, and unbiased investigation. This is noticed by every visitor to the ruins. His book may contain ‘formal defects’ but his main conclusions stand unshaken, i.e. that the culture was originally introduced from Asia at some period of pre-Islamic times.

George McCall Theal, author of History and Ethnography Alexander Wilmot: author of Monomotapa (Rhodesia): its

of Africa south of the Zambesi: from the settlement of history from the most ancient times to the present century

the Portuguese at Sofala in September 1505 to the

conquest of the Cape Colony by the British in

September 1795 and many other publications

Professor David Randall-MacIver (1873 – 1945) Theodore Bent, excavated at Great Zimbabwe,

British born archaeologist author of The Ruined Cities of Mashonaland

The prehistoric gold mines of Rhodesia – when was the gold extracted from the rock – not between 900 and 1760 AD

Portuguese Period, 1505-1760[9]

In recently published articles I have cited some of the evidence that the oldest gold mines sunk to depth on the rock in Rhodesia were ancient in the fullest sense of the word and mention the opinions of a succession of the highest mining experts, from Mr John Hayes Hammond in 1894 to Professor J.W. Gregory in 1905, all of whom had personally inspected the mines and were perfectly unanimous in their opinion that these were ancient. That they were sunk by people who were not only skilled in rock mining, but were acquainted with mining in the Near East, or India, or both, that they were not the work of any present Bantu people and that it was estimated that the ancient output of gold from Rhodesia from the rock at depth was over £75 million, which estimate was made before half the ancient mines’ area had been discovered.

On the other hand Professor Randall-MacIver who admits he never inspected any of the gold mines, repudiates any suggestion of an intrusion of foreign influence, or occupation into these territories earlier than that of the Magadoxo [Mogadishu[10]] Arabs in the 11th century, thus underrating the possible traffics and discoveries of the ancients and the influence they appear to have exerted by contact with the barbarous inhabitants of South East Africa. His exact words as to the date of the founding of the town of Sofala by the [Mogadishu] Arabs are, “There is no justification for ascribing to it an earlier date than the 11th century AD (RGS Journal, April 1906, P.336) Therefore to prove his case for the comparative modernity he claims for the output of gold from this country it is necessary for him to show the export of gold was not earlier than 1000 AD, but subsequently to sometime in the 11th century. Thus he [Randall-MacIver] proceeds (P335-6) “There is a great deal on the subject (output and export of gold) to be found in the Portuguese writers[11] and it is of some interest...”

Hall writes, “Of course it is extremely difficult to get any exact estimate of what has been extracted. Let us, for the sake of argument, take this suggestion which puts it £75 million.[12] A Portuguese, Alcáçova,[13] states the yearly sum taken out at the very commencement of the 16th century translated into English money was somewhere between £109,000 and £140,000. It would not take many centuries to run up to even such a figure at that rate.”

The Alcáçova ‘Fable'

Hall continues, “But for several weighty reasons the estimate of Alcáçova cannot be accepted, much less the present English value quoted by Professor Randall-MacIver. The letter of Alcáçova merely gives what was the Arab, not Portuguese, values of that time on the South East African coast. The reduction of Arab values of the early 16th century to those of the Portuguese equivalent of that period and the further reduction of such latter values to the English equivalent of the present-day, are Dr Theal declares, altogether unreliable.

Alcáçova distinctly states that the estimated values given by him were what the Arab said they had obtained in years ‘when the land was at peace’ and at some time altogether indefinite time previously to the arrival of the Portuguese in 1505.[14] but Professor Randall-MacIver omitted to state that the English values read by him into Alcáçova's letter were Dr Theal’s estimate, and further omitted to advise the meeting that Dr Theal in advancing what he admits to be this purely conjectural estimate, had in his footnotes and in his abstract in the same volumes, pointed out that the Arab values mentioned by Alcáçova were highly impossible, and that the reduction to English values of today was entirely hypothetical. Dr Theal wrote, “This is far beyond the real quantity” and he added, “no one is warranted in believing it possible and all the appearance and evidence was decidedly against it.”

Dr Theal goes on in the same volumes to show that even Portuguese authorities differed considerably among themselves as to amounts and values in very ordinary matters and cites one instance in which one authority states the value of a certain tribute at 2000 meticals[15] of gold and another authority gives 500 meticals. A metical was an Arab measure for gold dust which became such a standard measure throughout the south-eastern coast of Africa that the Portuguese on their arrival adopted it.

The records also state that Portuguese money was not in use at the trading stations. for instance, "money is not in use" (Nunez, II, 451), "the currency is gold dust" (Monclaros, III, 202), "there was none [money] at Sofala" (De Lemos, I, 74). Even in more recent times there was wide divergence in values. Dr. Kirk (1865) stated that in his day the coins of Mozambique were of different value, and that " 280 reis at the province were valued at 20 reis of Lisbon " {The Lands of Cazembe, p. 62).

But on other grounds the statements of Alcáçova, characterised by Dr Theal as "fables," have been challenged:

(1) In 1898 Dr. Theal, who had seen the original document written by Alcáçova, said the letter showed on its face, and apart from its contents, that the writer was an uneducated person.

(2) Alcáçova was at Sofala for less than twelve months, and immediately after the arrival there of the Portuguese in 1505 and before any Portuguese had penetrated into the interior. He wrote in 1506. He was a martyr to fever and never went inland. He misdescribes native practices. His statements of fact are irreconcilable, and are also flatly contradicted by his contemporaries, as will be seen later, especially with regard to huts of " stone and clay," while his credulity is simply astonishing.

(3) The whole of the records show that the Moors traded secretly and withheld all information as to their gold traffic, that they outrageously misled the Portuguese with regard to it, and that to protect their trade they avoided exciting the cupidity of the Portuguese lest they should usurp their commerce. Thus, we read, " They [the Moors] were very wroth at our coming, fearing we would dispossess them of their trade [in gold]" (III, 235); "As soon as they [the Moors] learned that the Governor's object was to discover the mines, by which they would lose their commerce, they had resolved to kill our men little by little with poison " (VI, 370)

Cova, in his work As Provincias Ultramarinos, speaks at considerable length concerning the early Portuguese

enterprise and the jealousy of the Moors at their advent.

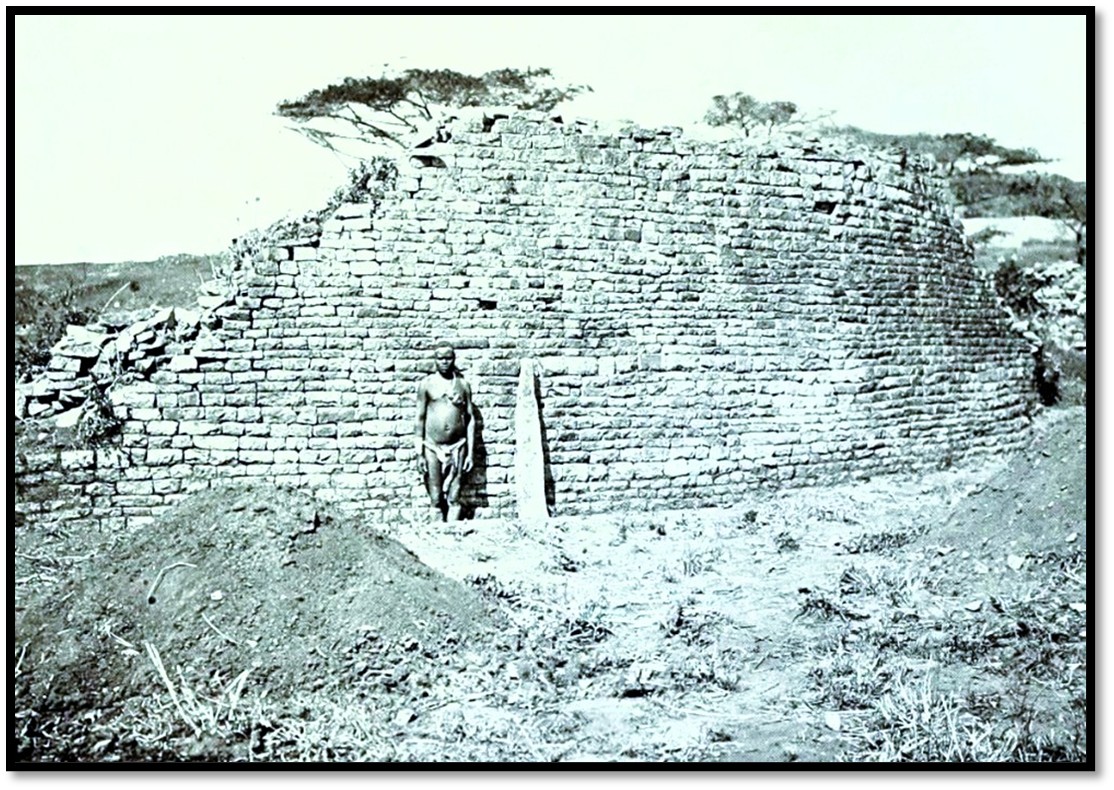

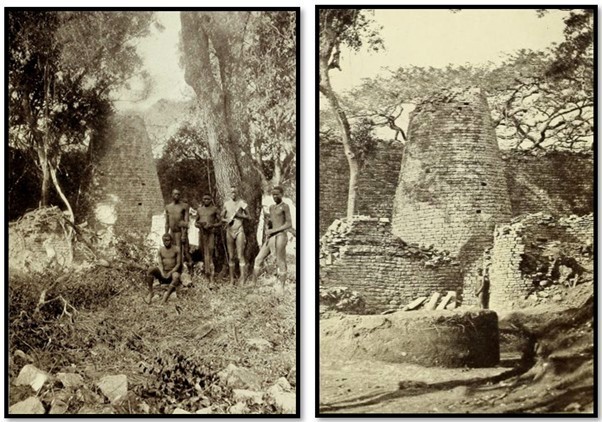

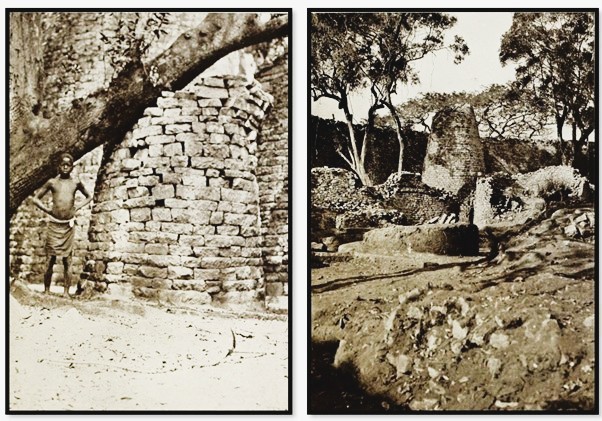

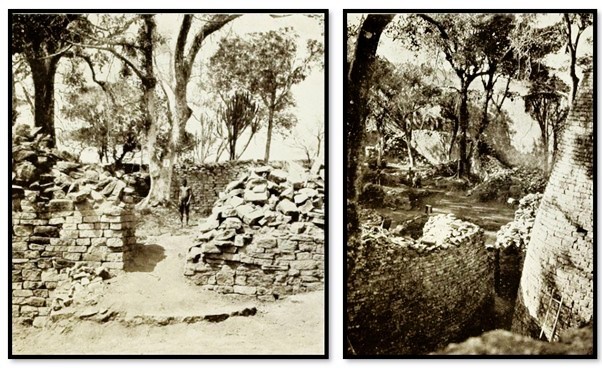

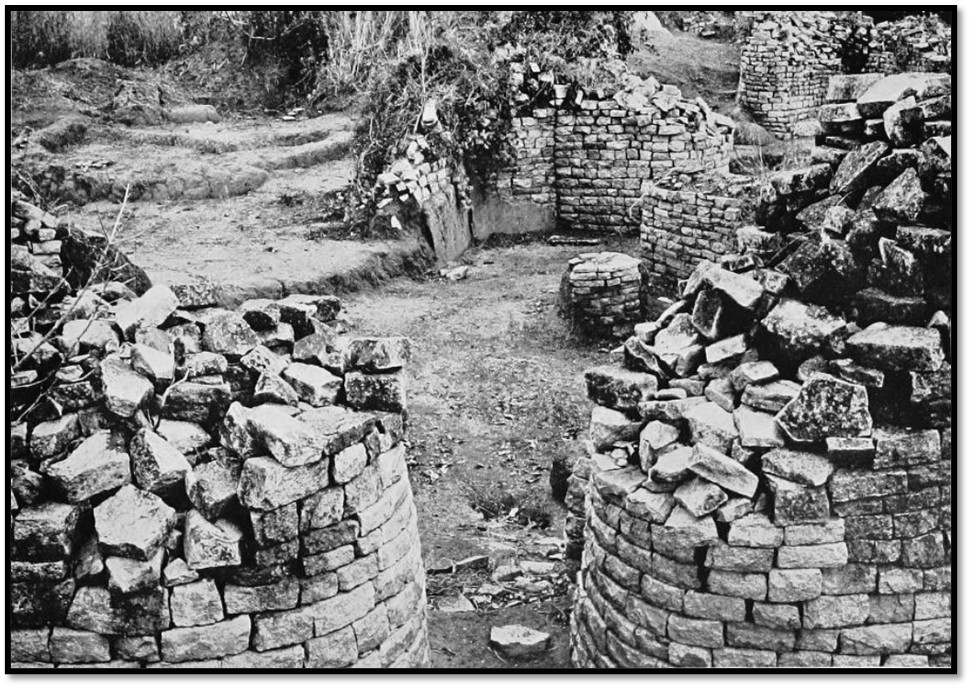

Hall: wall at Great Zimbabwe in the ‘Valley of Ruins’ currently called the Valley Complex

Refuted by Contemporaries

Dr. Theal writes, "The Moorish traders were particularly and not unnaturally jealous of the arrival of the Portuguese, perhaps not unlike the Portuguese are now of the British arrival. They made all the mischief they could between the Portuguese and the natives." Mr. Bent, in his Ruined Cities of Mashonaland (p. 236), states, "The Moors conduced to the martyrdom of Father Silveira. In fact, one of the great obstacles to the success of the Portuguese was the Moors' jealousy, which was at the bottom of the failure of all their expeditions up country." The suggestion that the Moors should, immediately on the arrival of the Portuguese at Sofala, have volunteered such a statement as alleged by Alcáçova is utterly incredible.

(4) No reference to such a trade as mentioned by Al Qaeda was made by Covilhã, who visited Sofala in 1487 (almost twenty years before Alcáçova wrote), or by Cabral, who was at Sofala in 1500, or by Ivar, who was there in 1501, or even by Admiral Vasco da Gama, who went to Sofala in 1502, " to obtain information " concerning the country (III, 99), and "to examine the market" (IV, 258), and who traded there for gold (V, 374) and " found little gold" (I, 50),[16] or by D'Aguiar or Alfonso in 1502, or D ‘Anaya in 1505, or Pereira, Barbudo, and Quaresma in 1506, or De Lemos in 1508. Even the historians Barbosa, M. Barretto, Lopes, Dos Santos, and Monclaros, all of whom visited Sofala and gave detailed descriptions of it and of its trade, are silent as to anything in the slightest approaching Alcáçova’ s estimate, but all state exactly the contrary as to the extent of the gold trade of Sofala. Two factors of Sofala, contemporaries of Alcáçova, in their official reports distinctly contradict his statement.

(5) Dr Theal draws my attention to the type of Moors on the coast from whom Alcáçova alleges he obtained his information. Dr. Theal remarks that it would be exceedingly difficult for even an intelligent educated Englishman of to-day to state what was the amount of coal exported annually from Great Britain, but it would have been far more so for any Moor of the type described in the more so for any Moor of the type described in the records to say what was the annual export of gold from the country of Sofala. It must be remembered that Isuf, the blind sheikh of Sofala, had been killed before Alcáçova wrote (I, 67). The Moors who traded at Sofala at that time from Kilwa, Mombasa, and Melinde, "are black men" only dressed from the waist downward, "some speak Arabic " (I, 94, 97) ; " all speak the language of the country [Chikaranga] " (III, 124 [**]

(6) But a fatal bar to the acceptance of the statements made by Alcáçova, and which information he said he obtained from the Moors of Sofala, is that, as pointed out by Professor Randall-MacIver himself in Medieval Rhodesia, p. 60, "The information is derived at second-hand from the same untrustworthy source', viz. the reports of the Arab [Persian?] intermediaries who traded to Sofala!' But at the R. G. S. meeting Professor Randall-McIver omitted to state that the information on which he relied, i.e. Alcáçova’s, was also derived from what he himself had already described as "the same untrustworthy source."

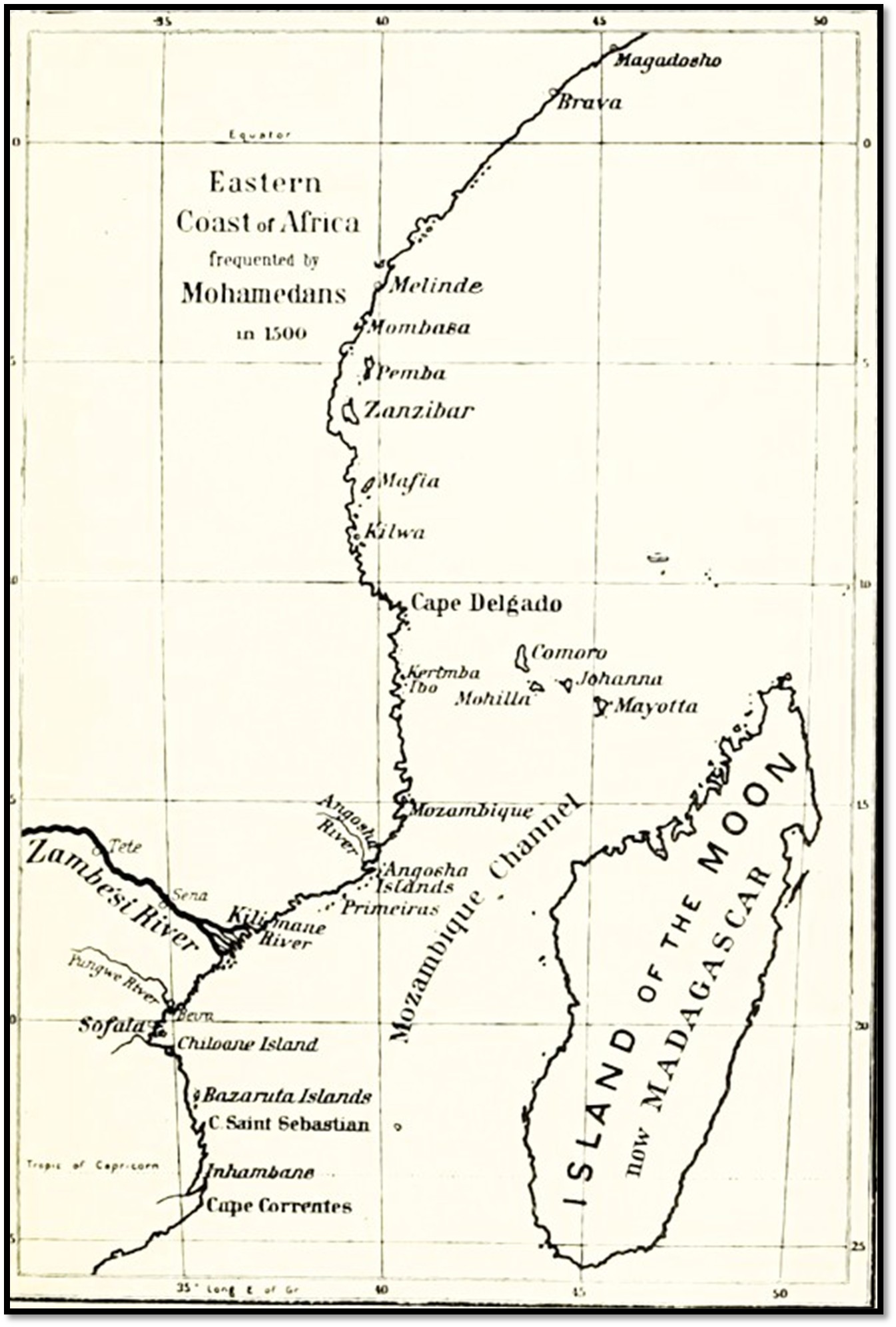

Native Mines and Miners

We shall now consider whether the vast amount of gold mined from the rock at depth in Rhodesia, or any appreciable portion of it, was extracted between 900 and 1760 A.D., when the Portuguese influence in Zambesia was broken. We shall divide this period into two sections — the Arab and Persian period, 900 to 1505 A.D., and the Portuguese period, 1505 to 1760, and deal with the Portuguese period first.

In the Portuguese records we read, the mines of Manica were “not much valued by their owners." "The natives with much difficulty gathered but a little gold in a long time, not being expert at that work" (Sousa, I, 15). The gold of Sofala "is plentiful in the country, but the natives barter very little " (De Lemos, I, 72). "The natives do not know how to extract gold except with water [washing soil, not mining], nor how to make the necessary implements with which to extract it from the bowels of the earth" (Bocarro, Decades, III, 355). "They are so lazy and given to an easy life that they will not exert themselves to seek gold unless they are constrained by necessity for want of clothes and provisions, which are not wanting in the land" (III, 355). A local writer, Father Monclaros, states, "They dig in the mines at certain times when they want to buy cloth to cover themselves" (III, 253). "The natives," Bocarro considers, "are more inclined to agricultural and pastoral pursuits than mining" (III, 355); the miners "only worked in winter [summer in South Africa] when the earth was soft " [in the rainy season — this is alluvial working on the surface soil, and not mining in rock] (III, 400) ; the natives only worked for gold in the mornings," until ten o'clock" (111,419). "In Mocaranga gold is only extracted in August, September, and October; in November, when the rains start and during the rainy season, there is no gold-washing, as the holes and rivers are flooded " [this is surface working in soil and river sand and not rock-mining] (Barretto, 1667 III, 489). He describes alluvial gold-washing from surface soil (III, 490) "All the gold found there [Manica] is dust" (VI, 266). De Barros describes washing surface earth for gold (VI, 240). "They [the natives] dive in the still waters of the river, and much gold is found in the mud which they bring up." "They obtain from the earth small particles of gold which we call gold dust" (VII, 367). "The natives are so lazy in seeking it, that one of these negroes must be very hungry before he will dig for it" (VI, 267). The natives of Manica "do not know how to sink mines" (VI, 367) "the natives of Butua, where there are rich mines, do not know how to obtain gold from any of them," and "only in the winter they go to the torrents which come down from the mountains, where they find grains and pieces of gold." "They are by nature so indolent that when they find sufficient to buy two pieces of cloth to clothe themselves, they will not work anymore." "They have no implements for digging deep." [**] (Diogo de Conto, VI, 367). The natives of Manica did not know how to work the mines, and only dug "earth," which was carried in small wooden basins (pandes) to be washed in the river, each one obtaining from it four or five grains of gold, it being altogether a poor and miserable business." "In the winter they searched for grains of gold in the rivers [when they were low]." The native "mines do not reach the vein" (De Conto, VI, 389, 390). Father Dos Santos, who lived eleven years in the country, describes washing surface earth as "mining" and states that the natives of Abutua, "where there is gold "do not dig for gold, "for they are much occupied with the breeding of cattle." (274). He further states, "The first and most usual [method of obtaining gold] is by digging the ground on the margin of rivulets and pools and washing the earth in bowls until it dissolves. For this reason they never dig earth anywhere but at the waterside" (280). [**] Dos Santos gives further descriptions, all identical, of washing surface earth for gold (288). De Goes states the gold bartered by the natives was "found in rivers and marshy ground." (III, 129). Dos Santos states, the gold taken to Mozambique, the chief factory of the Portuguese, is "generally taken out of the rivers every six months [in the dry season when the rivers are low]" (VII, 364). Ferao, Captain of Sena, states, "The gold dug from the earth is never more than at a depth of 4 ft (1.2 m) or 6 ft (1.8 m). As the natives are ignorant of the art of mining, the earth is washed in the rivers, by which means collecting the dust is very laborious." (VII, 379). Lacerda describes the "waist-deep holes" in which women worked for gold, the men being engaged in hunting, etc. (Cazembe, pp. 34, 49, 64, 71, 76). On P.62, I, of the records where "veins" are mentioned there is no suggestion of rock; "in soil," "dig earth," "collect gold," " gather gold " are the expressions used.[17] In every instance "veins" are the lowest strata of earth lying on the surface of the formation rock in which earth gold, owing to its weight, had lodged, and eye-witnesses of the natives' "mining" operations asserted that the "vein" in the soil ends without penetrating the rock (IV, 286).

Dos Santos further writes, "When the Portuguese found themselves in the land of gold [Manica], they thought they would immediately be able to fill sacks with it and carry off as much as they chose; but when they had spent a few days near the mines [soil-washing places] and saw the difficulty and labour [**] they found their hopes frustrated" (VII, 218). The records further show that the Portuguese were fully aware that the gold bartered by the natives was obtained from rivers; for instance, Sousa states, "the rivers of the country [of the Monomotapa[18]] have golden sands." (I, 15).

Dr Theal states, "The natives neither knew how to dig, nor had the necessary tools. Only by washing river sand in pools after heavy rains, these barbarians obtained all the gold that was purchased at Sofala" (VIII, 364). The localities of operations of washing surface earth the Portuguese in their usual grandiloquent style misnamed "mines." Dr. Theal further states (VIII, 478), " In none of the records still preserved is there any trace of ancient underground workings having been discovered by the Portuguese."

Manica and Mazoe districts comprise many areas of square miles in extent where the surface soil has been trenched over for gold. All mining engineers and surveyors working on the present mines on the rock in these districts have always asserted that the soil trenching operations are of mediaeval and post-mediaeval times, probably the work of old MaKaranga and BaTonga people, that the ancient mines sunk to depth in the rock of these districts are undoubtedly ancient in the fullest sense, these having been naturally silted in up to 150 ft. (45 m) in the course of centuries. This is obvious to anyone inspecting both the surface workings and the mines on the rock.

Reef-mining, if any, by MaKaranga and Ba-Tonga during the Portuguese period was on outcrops only ; that is by extracting the "vein stones" from outcrops of reefs, in the same way as can be seen in the Wedza district, where MaKaranga within the last few hundred years, and even lately, have followed along the line of outcrops for miles, taking only the "vein stones" of copper and iron ores without any sinking, and from positions where alone they could use fire and water to split the rock, a process impossible of adoption in the deep mines.[19] This nibbling of outcrops for iron and copper, but not for gold, was a common native practice not so very long ago.

But assuming for the purposes of Professor Randall-MacIver’s argument that a vast amount of gold had been obtained by the natives from washing surface soil and sand in riverbeds, and the records show most conclusively that this was not the case, such an amount, whatever it might have been, does not account for a single pennyweight of the more than £75,000,000 which has been extracted from the rock of the ancient mines scattered thickly all over the country, an area of 700 by 600 miles (1,126 x 965 km)

Bocarro (II, 399) describes sacrifices by the natives that the spirits of the dead might point out in dreams where the "mines" were ; that is, where the soil contained gold dust. This practice is very common to-day in the case of lost cattle or stolen property, but divining for gold is not exactly mining prospecting; yet this is but another of many evidences that the MaKaranga and Ba-Tonga of those days, and the "mining" operations of both these people is described in the same identical terms, were absolutely ignorant of rock-mining and also of assaying reef. Divination cannot possibly explain the extraordinary skill of the ancients in estimating the value of rock, the bulk of which, not showing a speck of visible gold, could not have afforded without assay and determination any possible clue as to its value. [**]

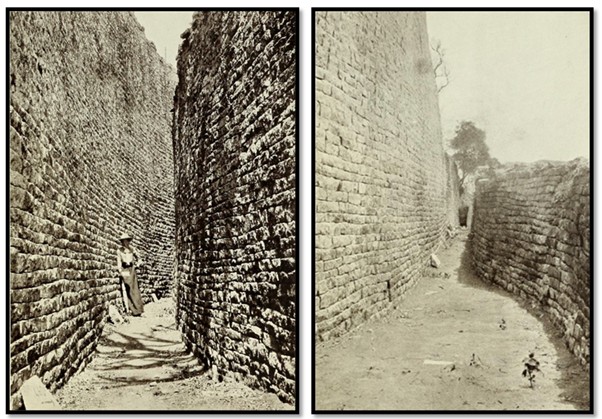

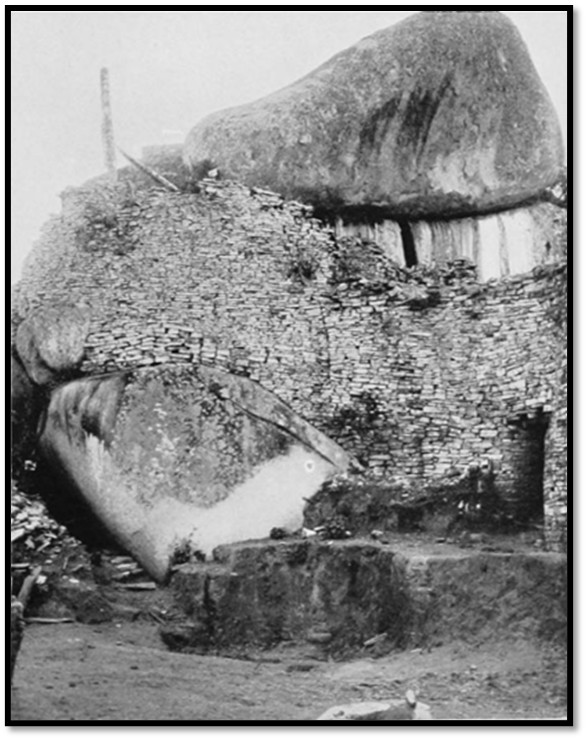

Hall: The Conical Tower at Great Zimbabwe

Prior to excavation After excavation 1902 - 3

Gold of No Value to Natives, 1505-1760

The ancient mines, sunk to depth in the rock, which cover an area of 700 by 600 miles (1,126 x 965 km) testify that the prehistoric miners valued gold. The Portuguese records demonstrate that the natives of the country of the Monomotapa’s cared nothing for it except as an article to barter for loin-cloths, blankets, glass beads, and brass wire; that, as to-day, their cattle and not gold formed their internal currency[20] and that they only washed surface soil for gold, and then only between harvest and sowing only bartering during one short period of the year, just as their trading to-day is confined to certain months of the year only.

Barbosa, writing of the trade as the Portuguese found it on their arrival, says, "The natives of Benemotapa exchange gold for cloth, without weighing the gold, in such a quantity they [the Moors] commonly gain a hundred for one" (I, 94, 96). Barretto (1667) states that the native chiefs do not wish gold to be dug for in their lands, because the Portuguese might buy the land from the King, and they would be despoiled of their lands (III, 483), or only such a small amount of gold as was sufficient to buy necessaries (III, 485). Even at Masapa, "where there were rich mines," cows were worth more than gold (II, 120). We have already seen that the "mines" of Manica were "not much valued by their owners" (I, 15).

Scarcity of Gold Ornaments of Natives, 1505-1760

Soares mentions that gold beads and trinkets were brought by the natives to Sofala, these only weighing 10 to 12 meticals (a metical, according to Ferao, = ¾ of an ounce) "making out that he is sending to him [the factor] the greatest thing in the world," i.e. that the natives not having many gold ornaments prize these small quantities (I, 82) The gold ornaments given to the Governor of Mozambique by the Monomotapa "did not weigh 10 meticals, the honours and value not being equal" (Father Monclaros, III, 248) Dr Theal states in his Abstracts of the Records that these small presents of gold beads were ridiculed by the Portuguese, and he considers that such ornaments were exceedingly rare among the natives.

The Arab writers of the twelfth century state that the natives did not wear ornaments of gold notwithstanding there was gold in Sofala, "nevertheless the inhabitants prefer copper and make ornaments of it," and also that they adorned themselves with brass and not gold ornaments. The records (1 505-1 760) contain only three references to gold ornaments being worn, and in two of these instances the gold in quantity ranks after iron and copper.

Ferao, "captain of Sena," states the natives "do not know how to work this metal [gold] and never apply it to any purpose" (VII, 379). The Portuguese records show that iron-smelting furnaces were not numerous, and they mention them as rarities. Authorities on the Bantu are unanimous in stating that no tribe of Bantu people have ever been known to weld metal. Lacerda only saw one native in Zambesia wearing gold "spangles" (split pellets, just as the natives of the present-day wear copper and tin spangles in their hair) and remarks, "but no one prized them" (p. 23), the chief of the Maravi informing him that "his people did not extract gold, because they knew not what it was" (p. 80), further, they did not do so "because their ancestors had not done so." Lacerda said that the natives did not know how to mine for gold, nor how to convert it into ornaments, and also that the natives did not value gold. All the writers very frequently refer to the brass, iron, and copper ornaments worn by the natives. For instance, "The negroes make of it [copper] their necklaces, bracelets, and anklets (yergas, wires [imported]) like carpet-rods, twisted round the legs," as also worn to-day.

But the evident scarcity of gold ornaments among these people to which the records testify appears to be borne out by the "finds." We are distinctly informed in the records that the MaKaranga did not make or wear large gold bangles and necklaces (I, 32), and yet out of the £4,000 worth of ornate gold ornaments found on the lowest and original floors in the older structures at Zimbabwe and out of the profusion of gold ornaments found in other ruins of the Zimbabwe type and age, the greater portion consisted of these large bangles and necklaces.[21] This points to an occupation of Zimbabwe and certain other ruins at some period very long prior to 1500 AD and also to the very general practice of wearing such articles. Moreover, gold bangles are stated to have been worn only by the Monomotapa himself, "an honour he grants to none and reserves for himself alone" (III, 248) This confirms the statements of W.G. Neal and myself in The Ancient Ruins of Rhodesia, written before the Portuguese records were discovered and based on our finds in two distinctly different types of ruins, that at any rate since 1500 AD, if not from some very much earlier period, the MaKaranga did not make or wear gold ornaments. In the graves of the natives of (about) that period, and of subsequent times, hardly any gold beads, if any, are discovered, nor in debris of the huts of such natives; nor are they to be found on the clay (dhaka) floors which yield the class of MaKaranga and Ba-Rosie[22] [Rozwi] pottery of a late period and of poor make with which Professor Randall-MacIver so freely illustrates his work; nor have they been, or ever will be, found in certain ruins of a late date and of poor construction said by Professor Randall-MacIver, but without the slightest warrant, to be the "prototypes" of the Temple at Zimbabwe. Every future explorer must meet with the same experience concerning " finds" of gold ornaments as were described seven years ago in The Ancient Ruins of Rhodesia of the very oldest type, in which the bodies lay in a horizontal position, also on the lowest granite cement floors of ruins of the Zimbabwe order, and then they were always discovered in rich profusion, "as plentifully as nails on the floor of a carpenter's shop." Gold will not, unless a stray bead or two, be found on the upper clay {dhaka) floors, or in connection with daga structures.

This evident scarcity of gold ornaments during this period provides a striking contrast with the circumstances of some much earlier period, and points to a decided divergence in culture. From 957 A.D., when AY Wardy wrote that the natives of the Sofala country did not wear ornaments of gold, we have a long succession of emphatic statements by Arab, Persian, and Portuguese writers to the effect that no gold ornaments were worn. Was the gold ornament wearing period at some time prior to 957 AD? All the brass wire bangles so far discovered contain a "core of vegetable fibre" (M.R. 76), but in fully a hundred instances of the discovery of gold bangles the "core of vegetable fibre" had completely disappeared. This alone points to "periods," and also to a wide divergence in culture.

Gold beads are also to be found in positions where they have been undisturbed for many centuries. One instance of several may be stated. In 1906 Mr. Garthwaite, consulting mining engineer for the BSACo , found gold beads 12 ft. (3*65 M.) deep in solid gravel which had never before been artificially disturbed, in a district where there were no ruins or mines, and nowhere near any river.

Unsettled State of the Country, 1505-1760

While the ancient rock mines in Rhodesia are shown by mining experts to evidence very long periods, covering centuries, of peaceful, unmolested, and well-organised mining operations, the period 1505-1760 is shown by historic records to have been one of continuous wars and of completest unsettlement and disturbance, precluding any suggestion whatever of natives raising within that period even the veriest appreciable portion of the vast amount of gold estimated to have been extracted from the rock of the country.

On the arrival of the Portuguese in 1487 they found the Arabs and Persians of Mozambique and Sofala to be engaged in a chronic state of warfare with each other, and with various tribes on the coast. "This constant strife," says Dr. Theal, "was the key to the easy conquest of the coast regions and islands by the Portuguese." The disruption of the "empire" of the Monomotapa’s, which had taken place long before the arrival of the Portuguese, still resulted in permanent feuds and constant wars in the interior.

The small amount of gold arriving at Sofala is attributed to native wars inland (I, 66) De Brito, factor of Sofala, in 1 519 reports, "This country is ruined," and that a chief of Quiteve had "reduced all the territories round this fortress" (I, 105). In 1569 Tete trading station was temporarily abandoned owing to wars (Monclaros, III, 202). In 1570 the Portuguese were fighting with the Quiteve, the king of the hinterland of Sofala (De Conto, VI, 388). Then followed the twenty years' war (1570- 1590) of the Muzimbas with other tribes, also with the Portuguese, which stopped all trade at Mozambique, Zambesia, and Sofala, the ill-effects continuing till the end of the seventeenth century (VIII, and generally). In 1592 there was a slight revival in trade, but later "matters along the great river (Zambesi) were in a worse condition than ever before" (III, 403). In 1602 "the Cabires, a warlike tribe, were in possession of the mines of Chicova, and the principal mines of the kingdom of Monomotapa" (King of Portugal to the Viceroy of India, IV, 50). Dos Santos states there was war "nearly every year" (VII, 273), and further states, "the natives went about in bands at variance with each other" (VII, 363). De Barros reports, "No gold has been extracted from the mines for years because of the wars" (VI, 268). In the Government reports (1584-1668) it is evident that the Kings of Portugal were more concerned for the safety of Sofala and Mozambique as naval depots on the route to India, which were threatened by the Dutch and later by the English than for their value as gold trading stations. In 1607 the crews of Dutch ships robbed and sacked the town and port of Mozambique (V, 285). In 1609 the chief trading station of the Portuguese at Masapa in Mocaranga was abandoned, "all the country was in arms against the Portuguese" (Bocarro, III, 383), and the Portuguese are ordered to withdraw from the Zambesi to Mozambique "to defend it from the Dutch" (III, 384). In 1615 the Chicova fort was abandoned by the Portuguese (IV, 158). In 1628 the King of Portugal writes, "The trade of the rivers of Cuama ['five mouths, 'Zambesi] is in a miserable state, "which he attributes to wars (IV, 213). In 1634 Dutch pirates rob the Portuguese trading ships off Sofala. In 1635 the Portuguese are at war with the kingdom of Manica (IV, 278). In 1651 English ships threaten Sofala coast ports. In 1667 "the settlement [Mozambique] is almost deserted " (Barretto, III, 480). In 1687 English ships trade in South-east Africa and seized the commerce of the Portuguese (V, 296). In 1719 "disorders [in Mocaranga] are frequent" (V, 66); "the vast empire [of Mocaranga] is in such a state of decadence that no one has dominion over it" (V, 72). In 1748 French ships visit Mozambique and usurp the Portuguese trade with the neighbouring islands and "the commerce of Querimba [an important trading station between the Zambesi and Mozambique] is entirely in the hands of the French " (V, 194)

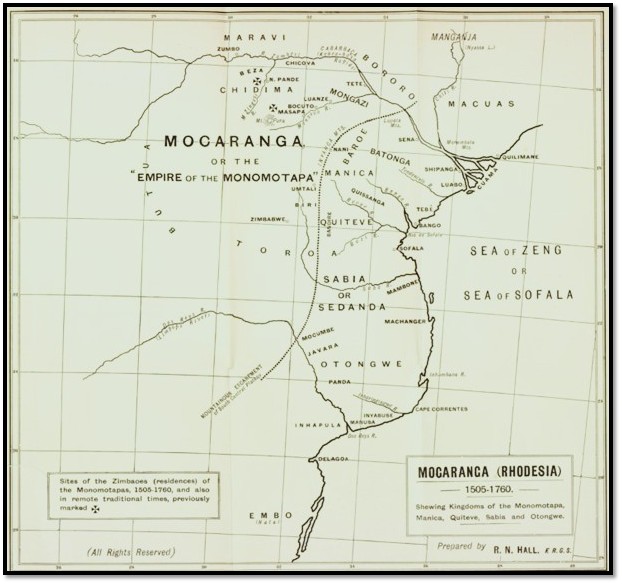

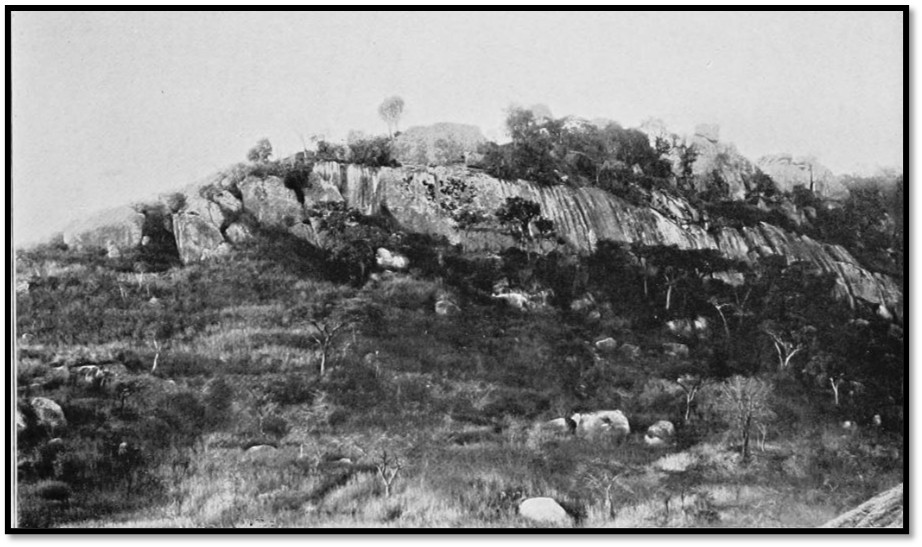

Hall: Monomotapa (or Mocaranga) in the sixteenth and seventeenth Century according to R.N. Hall

But, in passing, be it remembered that the records refer to that period, the stormy and unsettled times just described, which Professor Randall-MacIver claims as the very period during which the bulk of the Rhodesian ruins were erected, and as part of that period the greater, or at any rate a large, portion of the more than £75,000,000 of gold was extracted from the rock at depth. But the records make the acceptance of such conclusions absolutely impossible, though there is no doubt, as was contended by me almost ten years ago, that some of the small and poorer buildings, mere parodies of the earlier structures, were erected in subsequent times. Later we shall draw attention to the strange ignorance of the Moors and Portuguese that such colossal building operations and such skilled mining of rock (not soil or sand in rivers) on an astonishingly extensive scale were going on (so Professor Randall-MacIver invites us to believe), not only over an area of 700 by 600 miles (1,126 x 965 km) of country, but actually in those very districts where were the Portuguese trading stations. But not a rumour of such colossal undertakings, which Professor Randall-MacIver states must then have been in progress, ever reached the ears of the Portuguese! But to return to the records.

Portuguese Trade at Sofala* 1505-1760

On account of the poorness of the gold trade of Sofala, which place Duarte Barbosa describes as "a village" (1, 93), Alcáçova applies for a better position in India (I, 67). De Lemos, factor of Sofala, reports in 1508, the gold of Sofala "is plentiful in the country, but the natives barter very little" (I, 72). Soares, factor of Sofala in 1513, complains of the small quantity of gold bartered for. He says, "I see so few natives and traders from the interior that from then to the present time I have not bartered 500 meticals, and this though the whole country is at peace," and "the captains by presents had laboured to secure a commerce." "Although there is gold scattered over the whole country, no one has such a quantity that it is worth his while to come so far in order to barter it"; also he says, "There is not so much gold in this country as has been reported" (I, 80, 81). Soares also reports, “A great expense for so little revenue and profit, which is scarcely sufficient to cover the charges of the said establishment [Sofala]." He suggests the abolition of certain offices, also the reduction of salaries of officials and he states, "A factor and two clerks" were "sufficient to carry on the trade [at Sofala]"; and further, "There is nothing to prevent the traders coming here, if there are any" (I, 82, 83). De Brito, factor of Sofala, reported in 1519 that in eleven months he had only received 552 meticals of gold, which, he says, was insufficient to pay the official salaries of the factory, and "I am quite ruined [by farming the trade], and I wish I had not come here at any price;" trade at Sofala, he says, "is so dull that men have no heart " (I, 105, 106). Sofala as a trading station is declared to be useless {Ibid.) In 1552 official reports show a further serious decline in the gold trade of Sofala (III, 148, 149). In 1560 Father Monclaros states, "The favourable reports of the abundant riches of Monomotapa are not borne out by facts" (III, 302). In 1580 it was officially reported that "this fortress [Sofala] yields no revenue to our lord the King, except a small trade in ivory" (IV, 1). De Barretto writes, "Not a grain of gold is to be found in [the kingdom of] Quiteve " (III, 489), Quiteve being the immediate hinterland of Sofala, extending inland for 150 miles (241 K.). In 1585 Sofala was yielding nothing except the profit on a small quantity of ivory (VIII, 406). In 1634 Rezende, "the most competent writer of his day," reports that Sofala had no garrison, only three Portuguese residing there. He states, "The only commerce carried on was in ivory" also, "the only merchandise being ivory" (II, 405). In 1635 it is reported, "The fortress at Sofala is in a ruinous state, with no men" (IV, 255). In 1667 Barretto states that the principal trade of Sofala, "which is almost deserted," is " ivory" (III, 480) ; and later states his reasons to account for the small quantity of gold produced from the whole of the country. Ferao attributes the failure of the Sofala trade in gold to civil wars in progress in Quiteve (VII, 378, 380, 381).

Much has been made by the supporters of Professor Randall-MacIver’s conclusions of the reference to the "two ships of the Moors who had laden gold [1500] from that mine [Sofala] and were going to Melinde." (I, 48). The records show that owing to sand-banks ships could not enter the port of Sofala, and that all the transport along the entire coast of Mozambique was carried on in zambucos. On P 91, I, it is stated that "they [the Moors] came [to Sofala] in little vessels which they call zambucos from the kingdoms of Kilwa, Mombasa, and Melinde." The two "ships" were "zambucos" (V, 443)/ and Father Fernandes, 1560, says (II, 83) zambucos were small open boats "where there is no room for a man to stand, sit or lie down." De Goes states (III, 77), "The ships, or zambucos, in which these Moors sailed had no decks and were not nailed together but were fastened with wooden pins and cord made of palm fibre; the sails were made of the same palm tree closely woven together like mats." These boats, which only had one mast and one sail, were always drawn up above highwater mark when in harbour. In calms and contrary winds they were propelled with oars (VI, 171). Such, then, are the reports on the state of the gold trade at Sofala. But if such was the sorry state of the gold trade at Sofala from 1505 to 1760, in what position was the gold trade of Mozambique and Zambesia during the same period?

Portuguese Trade of Mozambique, Zambesia, and Coast

But Mozambique was the Portuguese centre both of the administrative authority and of the commerce for the whole of South-East Africa, including not only Zambesia and the country of the Monomotapa, and of Manica, Quiteve, and Sofala, but of Melinde, Mombasa, Kilwa, Magadoxo, Inhambane, Lourenco Marques, and of all the islands lying along the coast from Cape Delgado to Cape Correntes. All trading or barter goods for all these places were only obtainable, except by smuggling, from Mozambique, and to the central depot at Mozambique was sent all the gold, ivory, and other articles bartered from the natives at the sub-trading stations. The records explicitly state, as shown later, that no gold bars or ingot gold were ever sent to Mozambique from any one of the sub-trading stations of Mocaranga. All gold arrived in the form of gold dust, which on arrival was converted by Government assayers into bar gold. Mozambique was the only place where the official assayers were stationed. From Mozambique the gold was exported to India, only a small quantity being sent to Portugal. Consequently the state of the gold trade at Mozambique provides a fair index as to the state of the gold trade of the Portuguese throughout the entire South-East African coast.

The records show that at Mozambique the gold trade never flourished, but on the other hand was ever in a chronic state of depression, at times of stagnation and complete ruin. The vicissitudes of the island were at times exciting, varying from the chronic unrest of its Moorish population to sieges by the Dutch, the ruination of its trade by the French, constant fears of an English occupation, and a hostile native population of Maravi, who were cannibals, on the mainland, and who for long periods together not only refused a foothold to the Portuguese in their territory but denied to them the supply of provisions.

In 1503 the kings of Melinde and Mombasa were at war (III, 103), while "the Christians and Moors of Kilwa were always at war" (III, 79) In 1572 Monclaros, a local writer, states, "The people [on the Mozambique coast] are generally poor and wretched in nearly all these parts, and the Portuguese are becoming so already through the loss of the commerce and navigation taken from them by their enemies" (III, 216). In 1584 an official report states, "This fortress [Mozambique] produces no revenue for our lord the king" (IV, 2). In 1634 Rezende writes, "The Captain of Mozambique holds a monopoly of the commerce, he carries it on alone, with only one small vessel" (II, 405). The failure of the trade reduced the Governor of Mozambique "to beggary" (IV, 279).

The records show there was never at any time any trade in gold from the mainland of the northern Mozambique coast. "The Portuguese resorted to these rivers [on the Mozambique coast north of the Zambesi] to trade for ivory, provisions, and ambergris," there being not a single reference to gold (III> 223). Moreover, the Portuguese of those days, as Dr Livingstone and Sir Richard Burton have pointed out, never went inland on the mainland from Mozambique, while the records expressly state that the Portuguese possessed no knowledge of these regions for the simple reason that the natives, the Maravi, were a most dangerous and warlike people always at strife among themselves, and on every opportunity raiding the Portuguese settlements even on the islands along the coast.

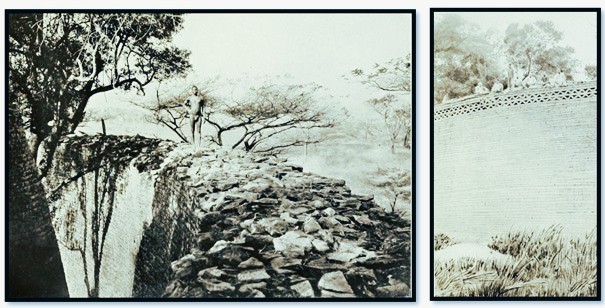

The Great Enclosure

Hall: ‘the small cone’ Conical tower and Great Enclosure after excavation

From the northern banks of the Zambesi the Portuguese traded with the Maravi, but for ivory only, and after 1645 for slaves and ivory. From the country of the Maravi, which was bounded on the south by the Zambesi, a territory extending for at least 200 by 200 miles (321 km) the records frequently mention that no gold was ever obtained, for instance, "In Maravi not a grain of gold is to be found" (III, 489), while Lacerda states that the Maravi had not the remotest idea of what gold was.

We find that the trade between Mozambique and Lourenco Marques, Cape Correntes and Inhambane was comparatively insignificant. One pangayo, a small boat propelled either by a sail or oars, was sent every year from Mozambique to Cape Correntes and Inhambane with trading goods for both those places, to bring back "ivory, slaves, honey, butter," there being no reference to gold (VII, 331). In 1630 it was said, "Inhambane, where there is a trade in ivory," gold not being mentioned (I, 22). One pangayo sufficed for the year's trade between Mozambique and Lourenco Marques, but it only brought back ivory, there being no mention of gold, and it is said the pangayo returned “half laden." (VII, 366). One pangayo every six months was sufficient for the trade between Mozambique and Angoche, whence was obtained "ivory, tusks of the hippopotamus, some ambergris, a number of slaves and very fine straw mats," there being no mention of gold (VII, 332). One pangayo every year suffices for the trade between Mozambique and Querimba, "millet and rice, cows, goats" being mentioned, but not gold. One also suffices for a year's trade between Mozambique and Madagascar, the commerce consisting of "cows, goats, ambergris, and slaves," there being no references to gold (VII, 332).

Owing to the chronic state of depression of the gold trade at Mozambique itself, Father M. Barretto wrote (1667) that "there was a proverbial saying in the mouths of the inhabitants and persons acquainted with these parts that all which is outside Mozambique is better than Mozambique." (III, 502) The inhabitants of Mozambique were noted as having a boast which was to the effect that there were more Portuguese buried there than anywhere outside Portugal. "It is the sepulchre of thousands of Portuguese" (III, 464). The records further show that owing to the poorness of trade the officials at Mozambique frequently became ruined and were always petitioning the Home Government for their removal elsewhere.

But the official documents and revenue reports given in the records disclose a most hopeless state of affairs at the headquarters of the Portuguese trade in South-east Africa. In 1590 Friar da Zevedo writes to the King of Portugal, "The kingdom of Monomotapa and the rivers of Cuama [Zambesi] at present profit you nothing" (IV, 35). In 1593 the King of Portugal writes, "My treasury in that state [Mozambique and Sofala] not only does not receive any profit from the trade of these fortresses but has also been obliged to bear the expenses thereof" (IV, 39). In 1593 Kilwa was destroyed by the Muzimba, who ruined the trade at Kilwa and Mombasa for many years (VII, 302). In 1623 the stations at the mouths of the Zambesi were "in a most abandoned state, and in want of everything, especially of men." (IV, 230). In 1628 the King of Portugal writes, "The trade of the rivers of Cuama [Zambesi] is in a miserable state" (IV, 213). In 1635 Quilimane station "is in a ruinous state with no men" (IV, 255). In this year, the Maravi tribe besieged Quilimane and stopped all trade (IV, 278). In 1684 the King of Portugal writes, the revenues of Mozambique "would not suffice to cover the necessary expenses for the defence of Mozambique and the rivers [Zambesi]" (IV, 423). In 1688, for three years, says the King of Portugal, there has been nothing for the Royal Treasury " because the decadence of the rivers increased every day" (IV, 449). In 1711 local tribes again besiege Quilimane and stop all trading (V, 33). In 1720 it is stated that "no profit whatever resulted from the trading, debts upon debts accumulating yearly" (V, 91). In 1720 the King of Portugal writes, "The debts [of Mozambique and the rivers to the Royal Treasury] have increased annually, the northern stations [Kilwa, Mombasa, Melinde declining more and more" (V. 74) and "that vast empire [of the Monomotapa] is in a state of decadence." In 1734 the King of Portugal writes, "I have seen your letter relating to the ruinous state to which the General Council of Mozambique and the rivers is reduced, being more than 200,000 cruzados in debt" (V, 175)

Portuguese Trade of Sabia and Limpopo Districts, 1505-1760

But the most astonishing feature in the records is the fact that they are absolutely silent as to any gold being obtained in the most important districts of Sabia and Limpopo, the evidences both positive and negative being that no gold was traded during this period from these territories. On this point the records are emphatic, and, further, they clearly prove that the Portuguese never visited them, and that what trade came from them consisted only of "ivory, ambergris, and iron, sesame and other vegetables" (VII, 186), and also copper, brought by the natives to Sofala, Mambone at the mouth of the Sabi, and Inhambane, and this only very rarely and in small quantities.

Yet the immense kingdom of Sabia — the records define its boundaries — which was traversed by the Sabi river, occupied by MaKaranga, and included the Great Zimbabwe (which the Portuguese never saw, and which is not the "Zimboache"[23] of Barbosa which he stated was in the kingdom of the "Benemotapa" which "Zimboache" was the chief zimbaoe or "residence" of the Monomotapa near Masapa in the Mazoe district), yields in its mines by far the best and most substantial evidences of ancient activities to be found anywhere in the whole of South-east Africa! To attempt to deal with the problem of the ancient rock mines between the Zambesi and the Limpopo without any reference whatever to these most important territories would be tantamount to discussing the play of Hamlet with the part of the Prince of Denmark omitted.

The Sabi provided in ancient times, and has always to this day provided, the only natural and possible trade route through the mountainous barriers of the escarpment of the central South African plateau from Sofala to the Zimbabwe country, while the Limpopo provided and still provides the natural and only possible approach from the coast to the ancient goldfields of Tati, Tuli, Gwanda, Belingwe and in fact, to the whole of the ancient rock mines area lying between those districts and the Murchison Range in the Transvaal; an immense area of ancient mining activities of the existence of which the Portuguese were absolutely ignorant. Evidently the scores of millions sterling of gold did not come from these two areas between 1505 and 1760, nor had the Moors any traditions concerning the great wealth which was once obtained from these sources.

Inland Trading Stations

None of the inland markets of the Portuguese, excepting Sena, were established until sometime after De Barretto's expedition in 1569, while the greater number were founded considerably later, some not being opened until over one hundred years after the Portuguese had arrived at Sofala in 1505, while there is no reference to others until 1749, about twenty years before the Portuguese power in inland South-east Africa was broken. The records further show that these markets have very precarious existence, also that some were only used for a very few years. For instance, Masapa was first abandoned in 1616 (I, 39), and there are references to later abandonments. The Portuguese were driven out of Bocuto in 1609 (III, 379). Chicova was established in 1614, and finally abandoned in 1616 (I, 41, 42). In 1572 Monclaros mentions Tete as "where the Portuguese formerly traded" (III, 226) and says, "Tete was deserted by our people" (III, 239), and he describes Sena as "a small village with straw huts" (III, 223). In 1616 and also in 1628 both Sena and Tete were raided by the Monomotapa (I, 43 ; II, 429). The factory of Chipiriviri was very short-lived, and being near Chicova, probably shared the same fate. In 1635 there were only "six men" in the kingdom of Manica (IV, 7), while the records show that the stations in Manica were abandoned at times for years together, some finally abandoned, and that in 1720 there was an attempt "to re-establish the fair of Manica" (V, 95). The only mention of Zumbo is in 1749, and only as a mission (V, 215), and of Massi-Kessi somewhat later still. Bandire was abandoned soon after its establishment (VII, 381).

The general unsettlement of the country from 1505 to 1760, as described earlier, accounts very largely for the short lives of these markets, but the introduction of the slave trade in 1645, as dealt with later, finally put an end to the Portuguese trade in gold. The Jesuit letters of 1740 (Wilmot's Monomotapa, P179) state that "all live in continual wars." But the policy of the Portuguese was equally as unaccountable for the general unsettlement as was the chronic state of native warfare or the Portuguese traffic in slaves. The Portuguese were always sending out punitive expeditions and to such an extent that in 1634 De Rezende wrote, "Those [natives] in the interior are in revolt against us and as we have often chastised them in war, they cherish a hatred of us" (II, 411) and he further explained the "petty commerce" by stating, "The negroes of these parts resent the punishments we have inflicted upon them." (416)

Moreover, these markets were only "annual fairs," that is, they were only open at one period of the year. The natives, the records show, did not wash in the rivers for gold except between harvest and sowing, also their trading was confined, as it is to-day, to one period of the year only. The Portuguese went annually to Masapa, Luanze, Bocuto, and Bandire, "where the natives from the interior go to wait for them at certain times."[24] (VI, 368 ; VII, 381)

The Great Enclosure

Summit of the East Wall Chevron pattern on the East Wall

Portuguese Farm the Gold Trade

The various fiscal policies adopted by the Portuguese at different periods between 1505 and 1760, as detailed in the records, afford further evidence of the slackness of the gold trade during the whole of this period. At one time customs are farmed, at another the whole gold trade of Mozambique is farmed, at other times the Home Government works the trade on its own account, while intervening periods of absolute free trade alternate with those of rankest protection, monopolies, and prohibitive tariffs. The fiscal policy was always in a chronic state of variation to either or any extreme, no system proving satisfactory. In 1598 "the mines of Sofala" were leased for £4,050 per annum (IV, 46). It does not speak much of the value the Portuguese placed upon their gold trade when we consider the terms of one of these farming contracts. In 1614 the whole of the Portuguese trade in South-East Africa in gold and ivory was farmed to the Captain of Mozambique, who is debited with £7,500 annually, and against this amount he is credited with expenses of the trading stations, forts, officials, and troops, but not with the tribute payable to kings and chiefs, and the balance to be sent to India (VIII, 460). Little wonder is it that the records show that in many instances the contractors became ruined, and that the Government was always being defrauded by its officials.

There are, however, two rare instances cited where those who had "farmed" the gold output had been successful. But these two fortunate individuals enjoyed the monopoly of all trading goods brought into the country, and though only a small trade in gold was transacted, yet the margin of profit between the price of such goods when landed in the country and their actual selling price to the natives was so enormous — amounting in some instances to a thousand percent — that with a small turn-over a most successful trading could be carried on. Thus we read, "A good deal [of profit on ivory] is gained by it in consequence of the trifling value here [Sofala] of the merchandise with which it is purchased" (I, 85) Correa mentions that "for a piece of cloth worth 150 reis was paid gold worth 750 reis" (II, 28) Monclaros, writing of the great profit to be made in trade, says, "One hundred cruzados may well be made to yield three thousand crusades" (III, 234). Cloth valued at 66 reis when landed at Sofala was worth for sale 2½ meticals of gold dust; that is, 66 reis bought gold dust worth 1,167 reis (I, 104) Loincloths sold for one metical of gold dust "apiece," that is, 467 reis per loincloth! (Ill, 234, and also, I, 85). But these "farmers" are shown to have made more money out of their extortions and also by licences and permits to trade sublet by them and by the issue of slave-trading licences, for which there was a brisk and constant demand, than they made by their own trading.

Still the majority of "farmers" were ruined by their contracts. Most wanted to leave the country and go to India or Portugal and boldly asked the king for their removal from East Africa. Promotion "elsewhere" depended on two conditions precedent, bribes (one "farmer" modestly describing “bribes"[25] as recompense for obtaining office (II, 414)) and glowing reports. The constant aim of "farmers" and officials is shown to have been promotion "elsewhere," nothing in South-East Africa

being considered good enough. "I pray your Highness graciously to send me away from these parts [Sofala] " (Covesma, I, 56). De Brito writes, "I am quite ruined [by farming the trade] and I wish I had not come here [Sofala] at any price" (I, 105, 106). One applicant for promotion "elsewhere" pathetically commences, "For God's sake!" (I, 26) and no wonder when the Governor of Mozambique himself was "reduced to beggary" because, as is stated, he had paid too big a bribe for his position (IV, 279). The poet Camoens, induced to take office at Sofala, met with rather unpoetic experiences in money matters at that port (I, 20). Alcáçova, who wrote that he was "ruined" and therefore unable to buy promotion " elsewhere," sends in a most glowing report based on "the information derived at second hand from an untrustworthy source, viz. the reports of the Arab intermediaries who traded to Sofala." (Medieval Rhodesia, p. 60), and it is his glowing report which exactly five hundred years later led Professor Randall-MacIver so seriously astray.

But the factors' reports allude to the smuggling of gold by the Moors. Surely Professor Randall-MacIver would not suggest that the £75,000,000 of gold was smuggled out of the country between 1505 and 1760? There is no doubt the Moors did engage in illicit trade. Dr Theal very fairly and impartially sums up the references in the records to such a traffic when in his History of South Africa (p. 285) he writes, "That a considerable trade was carried on by the Mohammedans with the Bantu in defiance of the Portuguese is highly probable, but that it amounted to a very large sum is not at all likely." The enforcing of the customs against the Moors was so rigid, that "according to Durate Barbosa they were reduced to such straits (' abject misery ') that they began to cultivate cotton and manufacture loincloths themselves, but this, if correct at all, can only have been on a very limited scale." But Alcáçova states that the gold from the country of the Monomotapa "does not go out through any other part [that is, not from Zambesi ports] except through Sofala, and something [smuggled gold] through Angoche, but not much." (I, 66).

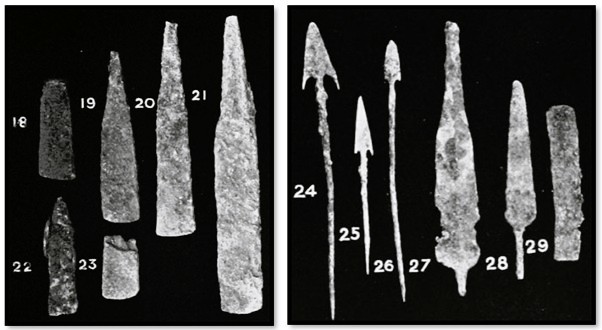

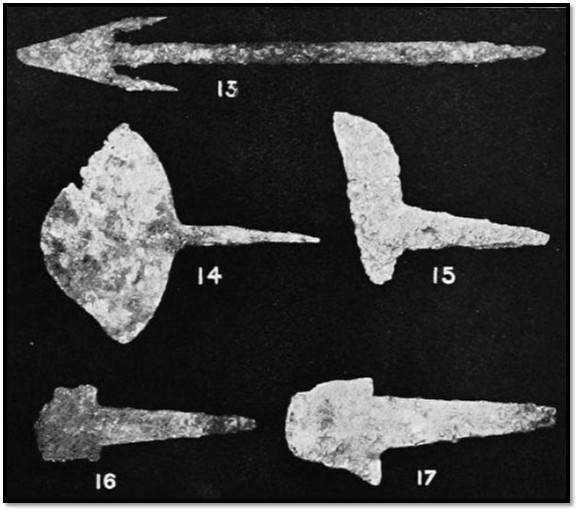

Randall-MacIver: Iron implements and weapons, Great Zimbabwe

Portuguese did not Mine for Gold, 1505-1760

The records are very emphatic in showing that the Portuguese did not mine in these territories for gold. Though excellent miners in Brazil, they had no mining engineers or assayers in South-East Africa. In 1619, after being in the country for over one hundred years, they had to admit to the Home Government that they had no mining experts and asked for some to be sent out (IV, 162), and the first assayers were sent in 1649, but to Mozambique only (IV, 307), and also that they had no miners (IV, 158, 161, 162). In 1634 pieces of conjectured silver ore had to be taken to Lisbon for assay (I, 42 ; II, 41 1 ; III, 235, etc). Two hundred years after their arrival they confess they had not found the gold mines! Probably not, for the ancient mines at depth on the rock can be shown to have been naturally silted in and almost buried long centuries before the Portuguese arrived in this country.

In 1629 the Monomotapa donated to the Portuguese certain mines, but, says the Governor-General, "up to the present time there is only the word of the said natives in proof of this [their existence]" (IV, 159). So incompetent were the Portuguese that in 1635 they most seriously declared, "The metal [gold] is formed by the sun on the surface of the earth" (IV, 286). They describe "golden quarries " with lumps of gold as large as a man's head [the Chartered Company would be exceedingly glad to locate and "reserve" these "golden quarries"] also that gold grew in trunks of trees, and that it "grows " and "sprouts' presumably after the fashion of cabbages (I, 22; III, 355, etc.) "like a large yam" (VI, 367). "Mountains of silver" were reported as having been seen (IV, 159)

Dos Santos, a local writer, describes how the deceitful natives had buried two pieces of silver ore in the soil for the Portuguese to discover and that when they were dug up with a "plantation mattock" " there was rejoicing and delight, and the trumpets and drums of the camp assisted in celebrating the discovery." (VII, 283) they also discovered a "red earth that has not yet been converted into gold, but which shows by its colour that it will so become." (281).

But the Portuguese, the records tell us, did actually attempt at a very late period to mine in the northern portion of Mazoe, and there only, and they scattered Nankin china, this "very valuable dating material round about their workings by the hundredweight.” Mr. Telford Edwards has shown this was the case. Pieces of their timbering for the roofs in their extensions of the ancient adits were taken to London for examination and about three hundred years was allowed by experts as their utmost age. The Portuguese cleared out some few small ancient rock mines[26] of the silted soil with which they had become filled up, but, as the records show, they soon abandoned what was only an attempt, "for commerce native truck trading] is more profitable," "and they left them [the mines]" (III, 233), "the trade in cloth being more profitable, especially in loincloths" (III, 253). Further, Monclaros, a local writer, states, "The Monomotapa gave some gold mines [probably alluvial areas] to several Portuguese, but because the expense of extracting the gold was so great, and so little was taken out every day, they would not have them." (III, 233). " Gold mines" to the Portuguese were evidently not worth acceptance, even as gifts.

In a letter written by the King of Portugal (1640) we find, "The steps taken up to the present have not shown that there would be any advantage in working the said mines, on account of the small profit obtained from them." (IV, 287). In 1645 we find the Portuguese trade in slaves to Brazil and India from Mozambique paid far better, on their own admission, than either gold-trading or goldmining, while the records show (the references cited before) that the ivory trade at Sofala was more profitable than the trade in gold ! We read, too, that the Portuguese slave trade destroyed the confidence of the natives in the Portuguese and ruined the trade in gold. Little wonder the King of Portugal's "Ultramarine Council" at Lisbon became so exceedingly downhearted, as the official correspondence demonstrates. One thing is evident, the "Ultramarine Council" did not receive any of "the missing £75,000,000 worth of gold " which had been extracted from the rock at depth in those very territories of Southern Rhodesia containing the immense area of deep rock mines, of which the records do not make a single mention , and from which , it is explicitly stated, the natives traded no gold, and in the recent exploration of which rock mines no thirteenth- or fourteenth-century article has ever been found.

The records definitely state that the Moors of 1505 - 1760 did not mine for gold, the reason assigned being that they found trading "easier." "They [the Moors] have no other occupation than trading" (I, 103). De Barros, speaking of the gold of the Moors, says, "The gold which the Moors obtain from the negroes" (VI, 169). The records contain innumerable references to the gold obtained by the Moors having been obtained by barter only.

Export of Gold Dust and Bar Gold, 1505-1760

From 1505 to 1593 the whole of the gold from Sofala, Zambesi, and Mozambique was exported in the form of gold dust only. On this point the records are very explicit. From 1593 to 1649 gold was exported from Mozambique to India and Portugal in the form of dust and bars. In 1593 there is an official order that "bars" of gold (which appear from the records to have been in the form of bar adopted by the Portuguese in Europe) were to be stamped on their extremities and in the middle with the royal arms (IV, 40). In 1649 the King of Portugal, being advised of "frauds discovered at Mozambique with respect to the gold dust, which is brought from those parts, dispatched assayers to the fortress of Mozambique and the rivers of Cuama [Zambesi] to remedy the frauds." (IV, 307). The first suggestions as to smelting gold dust and making bars appear in 1593. In 1635 are further orders that these bars were to be stamped with the arms of the crown, "in the same manner as in the Spanish Indies," in order to prevent any misappropriation (IV, 260).

The whole of the gold sent from the subsidiary trading stations of Sofala, Manica, Zambesi and from the country of the Monomotapa’s, to Mozambique, where alone the assayers were stationed, was sent, during the whole of the period from 1505 to 1760 in the form of gold dust only (IV, 360) moreover, "the currency is gold dust." (Monclaros, III, 208), therefore gold ingot moulds were not used in the interior by the Portuguese, nor by the natives, as these, it is stated, only traded the gold in dust form. [**]

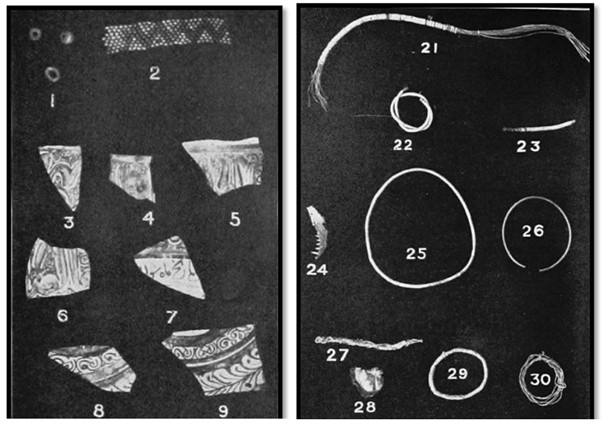

Randall-MacIver Great Zimbabwe excavated artefacts

Faience (Nankin) china imports Gold jewellery

Slave-trading Runs the Trade in Gold

In 1645 the Portuguese, being disappointed with the small amount of trade in gold, commenced to trade in slaves (IV, 302). The slave trade was at times a Government monopoly, and at other times it was "farmed." Licences to trade in slaves were sold at a high figure, and there was a brisk demand for them, which returned a revenue, as the records state, exceeding that derived from the gold trade, beside which the records show that the slave trade itself was far more remunerative than the slow business of bartering loincloths and glass beads for gold dust. But gold-trading could not be carried on simultaneously with the slave trade. With the introduction of the slave trade in 1645 commerce in gold ceased. Raids for slaves were, for at least one hundred years, carried on most extensively in the very territories which had formerly yielded the gold supply.

The Portuguese complained with most astonishing naivete at the disappearance of the gold trade, small as it had been, and whined because "the natives fled to other lands" Their fleeing is hardly a cause for wonder. Whole populations were decimated, and entire territories devastated. Dr Livingstone, in 1865, stated that the effect of this slave trade could be observed in Zambesia even in his day, while the traditions of slave-trading by white men, not Arabs, still exist among the MaKaranga of Mashonaland, who still possess many traditions as to the Portuguese occupation. (see Chapter V), Clearly there could have been no mining on the rock in such troubled times. We find from the records that this cruel and inhuman traffic completely destroyed the confidence of the natives in the Portuguese. The slaves were extensively exported to Brazil and other Portuguese colonies and were also supplied to the French colonies. Should anyone be interested to read of slave raids, the prices of slaves, and the profits of the trade, he should peruse The Records of South-Eastern Africa.

The Gold Trade - an Admitted Failure

The records contain, as can be seen, numberless official statements expressing the keen disappointment of the Portuguese at the non-success of their trade in gold and they admit they had nothing whatever to show in results to compensate them for the vast expenditure in troops and administration and for the appalling loss of life, "except a few dilapidated forts." Dr. Theal in his Abstract of the Records (Records, Vol. VII) points out that the official documents of the Portuguese Governments testify to the utter failure of their trade in gold. This failure was piteously but quite frankly admitted by all those most directly concerned in the "Conquest of the Mines." This "conquest" the records show was never effected, for the very simple reason that the Portuguese never penetrated as far as the ancient mines' area, concerning which they never obtained any information, apparently being altogether unaware of its existence. No rumour of large mines on the rock ever reached their ears, not even in the form of Arab tradition, or native legend. The records are absolutely silent as to the existence of any such mines.

Beyond the immediate vicinity of the Zambesi [river] they never penetrated. The entire period of their occupation was but brief. They only succeeded in obtaining a temporary and precarious hold on Manica and the northern portion of North Mazoe District, and even from these places they were repeatedly driven out. Yet the ancient mines' area extended beyond those districts for almost 500 miles (804 km) to the south and several hundred miles to the south-east and south-west, an immense country covered thickly with prehistoric mines sunk deep in the rock and completely filled in and buried in the course of centuries by a process of natural siltation.

De Lima, in his Possessdes Portuguezas (1859) in summing up the results of the "conquest" observes, "O illusoro Potosi de Chicova[27] ou 0 fabuloso El Dovardo de Quiteve”[28] but this applies only to that small portion of the country penetrated by the Portuguese. All modern Portuguese historians, without exception, confirm the story of the utter failure of the gold-trading ventures of the early pioneers of their nation in South-East Africa, and as did De Lima, describe the "conquest" as "illusory" and "fabulous."

In 1570 Father Monclaros, a local writer, reported, "Of the mines and abundance of gold and silver [of the country of the Monomutapa] many have written at great length, but the sum of what is known is much less than the reports which are current in Portugal" (III, 253). Again, "He [the king] had more favourable reports of the abundant riches of the realms of Monomotapa than were borne out by facts or came within our experience." (III, 202) Soares writes, "There is not so much gold in this country as has been reported." (I, 80-81), etc.

In 1619, over one hundred years after their arrival, the Portuguese were still engaged arranging for "the discovery and conquest of the mines [of the Monomotapa]" (IV, 161). In the same year it was stated, "there is no certainty of their existence" (IV, 160), and "experienced officials should first certify their existence." In 1622, presents are ordered to be given to the Monomotapa to secure his assistance in the facilitation of "the discovery of the mines." (IV, 184). In 1626 the Captain of Sofala is instructed "to search for the mines of Monomotapa" (IV, 194). In 1628 are fresh orders from the king for "search to be made for the mines of gold and silver" (IV, 218). In 1634 De Rezende writes, "Up to the present no gold or silver mines have been found." (II, 411). In 1667 Father de Barretto, a local writer, ridicules the existence of the gold mines and calls them "pretended mines" (III, 480). In 1697 the King of Portugal grants to Dominicans tithes of a reported mine at Sena, but taught by sad experience of misfortune, added, "if it is discovered." (IV, 496).

Thus, for one hundred and ninety years after the arrival of the Portuguese in the country they had never discovered the gold mines on the rock. As the Portuguese power inland became broken about 1760, there was only sixty years left in which to make the discovery, and this was not made even within that time. As late as 1719 the King of Portugal was doubtful about the existence of gold mines in the country, and he ordered inquiries to be instituted as to whether the Monomotapa (in 1607) did actually donate any gold mines to the Portuguese, "so that in the future, when there is a better opportunity, we may avail ourselves of his donation." (V, 72).