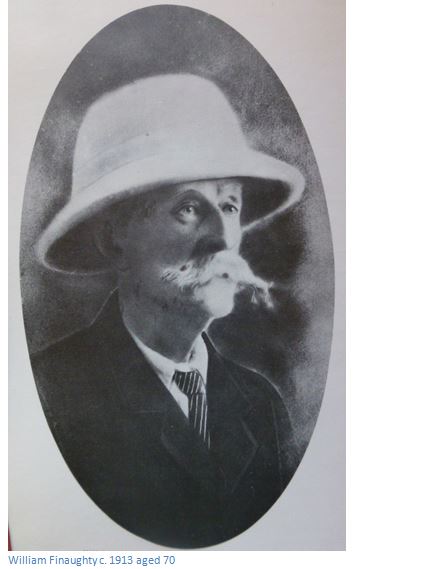

William Finaughty (1843 – 1917) one of the great elephant hunters who knew both Mzilikazi and Lobengula and brought the two ship’s cannon now at the Natural History Museum in Bulawayo.

William Finaughty, “Old Bill” knew Mzilikazi well. Born in Grahamstown in 1843 he left home in 1864 for the interior and accompanied the traders Edward Chapman and William Francis to Matabeleland. He returned to Kuruman and worked in Chapman’s store in early 1865 before accompanying Chapman back to Matabeleland and staying there to trade. He Was back in Kuruman in March 1866, but returned to hunt in Mashonaland with the Phillips-Gifford and Hartley parties.

He shot regularly for ivory until 1870, also doing some trading for ivory, cattle and ostrich feathers. Eric Tabler estimates he shot about 500 elephants in 5 years, Henry Hartley is estimated to have shot 1,200 in a hunting career of 30 years, so Finaughty had a big bag in a comparatively short time. Between 1871 – 1875 he traded in Shoshong with his brother Harry and during this time he bought three antique ship’s cannon in Port Elizabeth; one they tried to smuggle to Chief Sekukuni, but were blocked by the Boers; the other two they sold to Lobengula for ivory and today they are displayed at the Natural History Museum in Bulawayo.

In mid-1864 from the drift at Tati River, it took Edward Chapman, William Francis and Finaughty five days to reach Matabele country where they were stopped by Matabele guards and their arrival reported to Mzilikazi. Travellers were always detained here by the Matabele guardian of the gate, Manyami, until Mzilikazi’s permission was obtained and he “gave them the road.” However, as Chapman had been each year since 1860, they were allowed to proceed slowly and reached Mzilikazi’s kraal.

Finaughty says Mzilikazi seemed pleased to see them, especially when he was persuaded that Francis and Finaughty were English and not Boers, whom he disliked. By that time Mzilikazi’s health was poor, his lower limbs were paralysed and four wives carried him around in an armchair, but Finaughty says he still enjoyed a laugh and a joke.

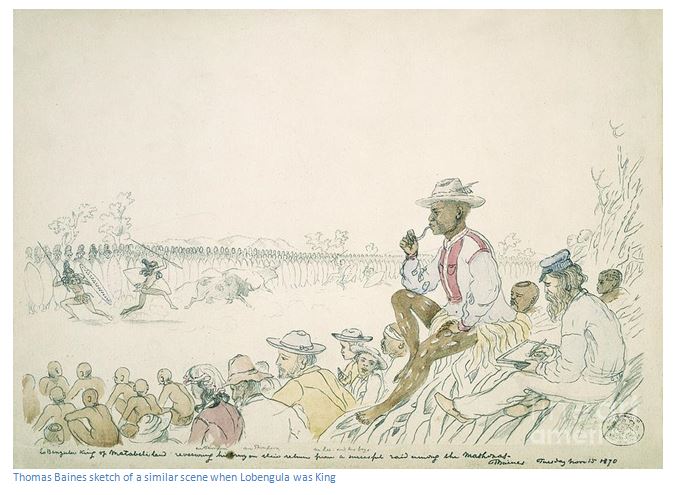

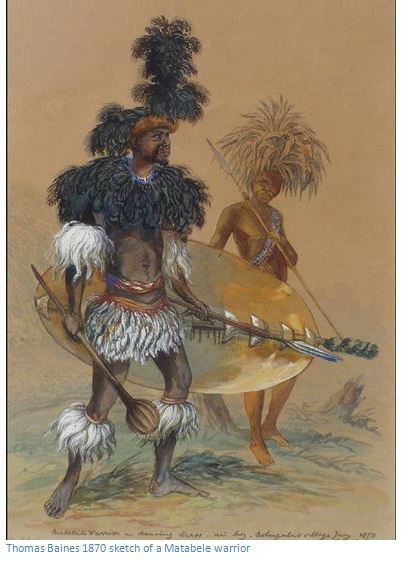

He describes a big dance, where 25,000 warriors in their war-dress, wearing plumes and carrying assegais and shields danced around the camp fires at night. Their singing, the drums and the thud of their feet made a wonderful and impressive spectacle and made a great impression on a young Finaughty of the might of the Matabele nation. William Francis and he counted five hundred and forty oxen slaughtered for the feast. The party stayed several months at the King’s kraal, Chapman securing about 5,000lbs (2,267 kgs) of ivory and Finaughty did some hunting. He describes the return of an Impi of some 4,000 warriors from a Mashona raid that got the worst of the encounter and returned empty-handed. Mzilikazi was disgusted and made them all dance for four days and nights without stopping. He describes the sight as terrible as the leg-weary, starving men danced hour after hour; knowing to stop dancing would be to stop for ever. He and Francis were present when Mzilikazi stopped the dancing and they were brought raw meat. One man took such a mouthful he could not swallow it and began coughing and choking. “Take the dog away” said Mzilikazi and the unfortunate warrior was hit on the head with a knobkerrie and dropped dead.

Finaughty describes the enormous herds of cattle which were distributed between the various kraals, each with an Induna in charge and says it was a picture to see them going out in the morning and returning at nightfall. In the kraal the herd of black, white or red cattle would be mixed, but when they grazed they separated into their respective colours, it was a sight which clearly made a big impression on him which he remembered until old age.

He remembered a wild ox that would not take its usual place in the kraal that Mzilikazi told his men to bring in. Finaughty heard the singing as two or three hundred warriors brought in the ox on their shoulders saying how they had captured the culprit that tried to defy the great Chief! He recounts how the same thing happened to a crocodile who took a child and when Mzilikazi said “bring them both to me;” the dead child and live crocodile were both carried to his kraal.

Edward Chapman told Finaughty that in 1863 he sold Mzilikazi a wagon and when Mzilikazi came down to the outspan with the agreed amount of ivory, but Chapman still had to off-load the wagon of its trade goods and provisions. Mzilikazi saw this, looked annoyed and said “what are you taking the inside of that wagon out for? When I sell you a bullock, I don’t take its’ insides out before handing it over.” It took some time for Edwards to convince Mzilikazi that a wagon did not include all its contents.

Finaughty adds that Mzilikazi would not permit any prospecting in the country. He did not mind a few traders or hunters, as they brought him goods he desired, and every visitor was accompanied by a Matabele guide, but also a spy who reported all things to Mzilikazi. Finaughty says the men who entered Matabeland at that time were interested in ivory and cattle and not gold. He says Thomas Baines, who they met at Mangwe Pass, was the first to say he had found gold nuggets on the Umyati, somewhere near present-day KweKwe.

Mzilikazi treated them well, sending beer and meat almost every day. A great contrast to what he describes as a typical days menu for a hunter when there was nothing “for the pot.” A daily ration of a biscuit and cup of tea in the morning, a biscuit, one tin of sardines amongst three and a cup of tea at midday, and at night coffee and a biscuit again…not exactly a Grand Hotel banquet!

Finaughty tells a story about the missionaries at Inyati which occurred about 1866. Thomas Morgan Thomas had invited Mzilikazi to Sunday Service and to hear a short sermon. Mzilikazi and his indunas attended, along with Edward Chapman, Richard Clark and Finaughty. Thomas began his sermon saying “God made the World, God also made the Sun.” Up jumped an excited and indignant Induna: “You lie, Thomas, Mzilikazi made the Sun!” There was a chorus of approval from all the Matabele and the four wives who were the King’s bearers picked up his armchair and carried him out showing they believed in the divine right of their King.

The same year Finaughty made another trading trip for ivory and cattle with Edward Chapman, Richard Clarke and Hans Hai. They joined Phillips, Gifford, Thomas Liesk and three others and combined with Henry Hartley’s party to go hunting in Mashonaland. Finaughty had no horse, so Hartley lent him one in return for half of what he shot. The horse he describes as a brute, nobody could ride him and the first time Finaughty mounted him, he was thrown, but he persevered and taught him better manners! On their first hunt, Finaughty shot all four bull elephants. Next time he shot three more bulls, the rest of the party only managing two. After shooting another bull and a cow, he could see old Hartley was unhappy with just his half share, so he left for Shoshong.

He made a third trading trip to Matabeleland and he did some more elephant hunting, so successfully that he decided to do it full-time and equipped himself on his return to Shoshong. He travelled with Phil Francis (who died on the Zambezi) and David Napier. They hunted on the western edge of Matabeland along the Shashi and on their first encounter; Finaughty says the bank was black with elephants. He had only eight musket balls, but managed to bring down six bulls and a cow, an amazing feat with an old muzzle-loader using black powder. Napier and his horse had been charged and trampled by an elephant cow and although he survived was black and blue all over his upper body.

After a few months Finaughty had thirty-eight pairs of tusks, while Napier had seven and after sending their ivory back to Shoshong they decide to ask Mzilikazi for permission to shoot in Mashonaland. Jan Viljoen, Piet Jacobs and their party in 1865 had been the first to hunt in Mashonaland and shot over 200 elephant. Finaughty had been with the Hartley party in 1866, but they had no great success, apart from Finaughty.

He says the elephants were not alarmed by the sound of his old muzzle-loader; although it was hard work carrying the heavy gun all day, powder loose in one pocket, caps in another and bullets in a pouch. The gun kicked like a mule and his shoulder was black and blue after a day’s elephant hunting, on a number of occasions the recoil knocked him out of the saddle.

On this trip he came across a wild white man who they ascertained had come in from Tete, or Sena on the Zambezi and been lost for four months in the bush. His clothes were rags, he was half-starved and Finaughty was amazed he had not been devoured by lions. Although he seemed to understand the direction of their wagons, they never saw him again. At the same time they received messages from Mzilikazi to return immediately. On his return he encountered the wagon of Mrs Harmse, whose husband, five of six children and Thomas Wood had all died of fever along with all their servants, except for one.

On the return, he had another close encounter when the cap on the musket fired, but failed to ignite the powder charge. He gave it to his gun bearer who put on another cap and another charge of black powder; meanwhile he had wounded the elephant in the shoulder with his second gun. He now fired the double charged gun which exploded and threw him on his back with the elephant nearly upon him. He scrambled away, but awkwardly in the sandy bed of the Sweswe River; fortunately the elephant’s wound in the shoulder prevented it moving any further and he was able to finish it off. The charge was a handful of black powder and the bullet weighed almost a quarter of a pound.

The old muzzle-loaders were also liable to hang fire; so the cap went off, but the fire only crept down the nipple of the gun, before touching off the main charge. On the same journey this happened a few feet from a rhinoceros, but he kept the barrel pointed at the animal and when the gun went off, it wounded the rhino in a vital place, so that it ran for about 400 yards and fell dead.

On their return they heard that Mzilikazi was near death. With no successor, Finaughty and Napier found the Matabele were extremely restless. As the wagons came into the kraal, about two thousand warriors surrounded them making threatening gestures, beat up some of their servants and placed their assegais against the wagon sides, apparently only waiting for a signal before falling upon them and “eating them up” in Matabele style. Finaughty recognized Mbiko Masuku, Induna of the Zwangendaba Regiment (later killed by Lobengula) and presented him with blue-crane feathers and two bars of lead (for making musket balls) who, with a few sharp words, orders the warriors back. He tells Finaughty not to stay too long at his camp down on the Bembezi River, a hint that Finaughty takes to heart and left as soon as possible.

On his journey back to Shoshong, he tells of an enjoyable stay with Old Jan Lee and his family at Mangwe River. The old boy would tell great yarns about hunting elephant for hours on end, whilst his son would be whispering that his father was too frightened to go near an elephant; that he had never shot one and was never likely too! Lee’s land was granted to him by Mzilikazi, and he became an informal foreign minister to both Mzilikazi and Lobengula with most hunters and traders stopping at his house during the 1860’s, 70’s and 80’s. He would not fight the Matabele during the 1896 Rebellion and the BSA Company confiscated his lands.

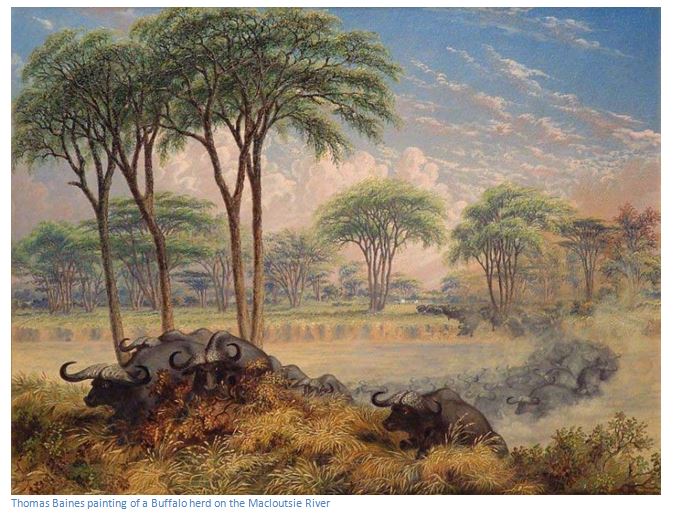

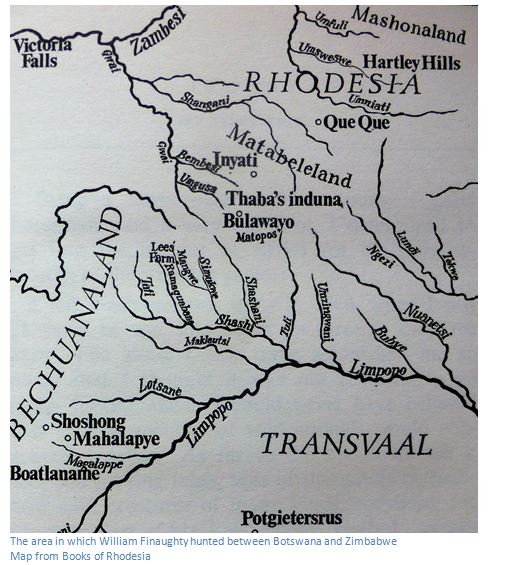

From January 1869 to 1871 Finaughty lived the life of an elephant hunter in the area above the confluence of the Tuli and Shashi Rivers, sending out his ivory and only leaving to replenish his supplies. This was part of the area between the Macloutsie and Tuli Rivers which was always in dispute between the Matabele and Khama, Chief of the Mangwato, but remained a neutral buffer zone. The usual hunting season was between May to November, when the trees were leafless and game more easily followed.

In this area he shot an old bull elephant whose tusks each weighed 90 lbs (41 kgs) and another whose tusks together weighed 250 lbs (113 kgs) His brother Harry became lost for nine days; some San hunter gatherers finding him eighty miles away and brought him back. That finished Harry’s elephant hunting. When elephant were not about, they shot rhinoceros for the horn and the hide for sjamboks. He also says that the hunter-gatherers would steal oxen if they could, that they were difficult to follow as they resorted to backtracking to mislead pursuers and usually killed the oxen for meat. They killed buffalo for riems. He describes how the hides were cut into strips and then tied to a tree branch with a heavy weight below. A stick is used to twist the riem as tight as possible; when the stick is pulled out, it unwinds with great speed. This process continues for three days and results in a strip of hide as strong as wire rope, but soft and supple. The feathers of a cock ostrich were each worth about £25.

On this 1869 trip Finaughty first took Cigar, a little Hottentot boy, from Grahamstown and who later features in Selous’ book A Hunter’s Wanderings in Africa. Cigar kept half of what he shot; three of his men were paid in wages, while the remaining forty-two would receive a musket, powder, lead and caps at the end of three months. As soon as they crossed the Macloutsie River, he shot three bulls with ivory of 300lbs (136 kgs) He says elephant fat is white like fat-tailed sheep fat, never gets hard, is excellent for cooking and can be eaten on bread like butter.

He describes encountering an elephant lying in wait for him and firing hurriedly from 12 feet (3.6 metres) …the bullet passed nearly through the elephant and he was able to cut it out and use it again. That day, a Sunday when he usually did not hunt, he killed six elephants with five bullets. On the Shashani River one of his oxen was stolen by a San hunter-gatherer (Finaughty says a two-legged lion)whom he hunts down and to his surprise finds he has a gun which he fires at Finaughty only just missing him and showering him with dust. The hunter-gatherer makes a run for it, but does not get far.

He says that was never keen on hunting buffalo as there is too much risk to horse and rider, in his opinion the buffalo was more dangerous than all other animals and tackling a herd of buffalo the most risky sport in the world. He says he would never return on the track of a wounded buffalo for fear it would waylay him. On this trip one of his horses was killed by lion and he hunts them; killing seven of them in the day and says in those days the skins were valueless, so they never skinned lions. On his way back with some 3,000lbs of ivory he comes across Sir John Swinburne and a party of prospectors and enjoyed a good evening sing-song with them.

Finaughty’s last trip was in 1870 when he shot fifty-seven elephants with nearly 3,000 lbs (1,360 kgs) of ivory and riems, whips and sjamboks worth £300. His favourite hunting ground was east of the Shoshong-Matabeleland Road and north of the Shashi River. Selous states he quit thereafter because by then most of the elephant had retreated into country infested with tsetse fly where they had to be pursued on foot and Finaughty preferred hunting on horseback. From then on he settled down to a trader’s life at Shoshong.

He lived in Kimberley in 1877/ 1878 and traded at Mamusa and married Elizabeth Krause of Bloemhof, they had four sons and six daughters, but he left at the start of the Anglo-Boer War of 1880-81 living in the Transvaal until 1887 when he settled in Johannesburg.

In 1894 he moved with his family to Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) and farmed first in the Matobo. It is said that at the outbreak of the Matabele rebellion in 1896 his wife took herself and the children into the Bulawayo laager because he was plundering the farmhouses of those who had already fled! He farmed at Umgusa until 1914, when he moved to his son William’s farm on the Kafue River in Zambia where he died in 1917.

His book was written from a few notes and verbal memories to R.N. Hall and was initially published in weekly instalments in The Rhodesia Journal, A weekly Newspaper of Rhodesian Information published in 1911 at Bulawayo. Finaughty at 70 was described as slightly built about 6 feet tall with “a face like the Duke of Wellington’s.” Of all the great hunters of the nineteenth century only Henry Hartley, Fred Green, George Wood, Jan Viljoen and Piet Jacobs had bigger bags. His recollections include most of the missionaries, hunters and explorers including Baines, Hartley, Viljoen, Selous, Mauch, Mohr, Moffat and Thomas and of course the Matabele Kings, Mzilikazi and Lobengula.

The two ship’s cannon in the Natural History Museum at Bulawayo

Finaughty wanted to sell one of the three cannon he owned to Chief Sekukuni in the Northern Transvaal in return for diamonds, which it was rumoured, Sekukuni possessed. In 1875, he and his brother hid the cannon under a false floor of their wagon, but somehow the Boers got wind of its existence and near Rustenburg they were arrested. They managed to outwit the Boers by giving them a bottle of brandy, so they slept soundly, whereupon they unloaded the cannon and buried it in an old game pit and led their oxen over the ground to hide all traces. They appeared before the Magistrate at Rustenburg, but as no evidence could be found, they were reluctantly freed!

Finaughty never found this cannon again, but apparently someone did. Cran Cooke quotes a letter from Major Angus Cree in 1954 which reads: “I believe when the siege of Mafeking started, the defenders found in the town an old smooth bore muzzle-loading gun of small calibre with the gun founders initial B.P. on the chase. This was regarded as a particularly good omen and the gun was used during the siege.” The reference to B.P. being interpreted as Baden-Powell! Hero of the Siege of Mafeking and founder of the Scout movement often referred to as "B-P."

In 1876, Finaughty went through Bechuanaland (now Botswana) to Bulawayo and was received by Lobengula, who said he didn’t understand how the “Billy” he knew, who used to hunt all his big game and elephants, allowed half a dozen Boers to take him prisoner. Lobengula and his sister treated the earlier encounter with the Boers as a huge joke! Finaughty said sold the two cannons, which at the time had no gun carriages, for £190 of ivory.

This cannon was probably cast at Carron, Scotland by B.P. & Co. Over the initials is a crown, indicating it was cast for the Royal Navy. It is the smaller of the two cannons with a bore of 85 mm and a barrel length of 1.13 metres. The date could be 1782, or 1802.

This cannon marked B.P. & Co. Cooke thinks was probably cast at Carron, Scotland in 1808. It is the larger of the two cannons with a bore of 110 mm and a barrel length of 1.013 metres and would fire a ball weighing 3.0 kg. Although cast as a ship’s cannon, it was not for the Royal Navy as there is no crown under the initials.

Cran Cooke quotes a 1910 letter following the re-discovery of the two cannon from Alfred Cross. Cross writes that he thought there were about five white men in Bulawayo at the time and said that Finaughty (who he describes as F) had bought the cannons in Grahamstown where they had been decorating a garden after Lobengula had agreed to buy them for 40 head of cattle. Finaughty told them he took the two cannons from Kimberley north, but on passing Zeerust was informed that the veldkornet intended to search his wagon the following day. Finaughty quickly buried the cannons and their brass ball moulds in a vlei and travelled on as fast as he could. The veldkornet caught up with him, but finding nothing incriminating, let him go on. He camped on the junction of the Marico and Crocodile Rivers and hunted for about a month, before returning to the vlei and recovering the cannons and one mould, the other was not found.

The guns were unloaded and inspected by Lobengula who said he had been told they would knock a hill to pieces and added: “when you show me they can do it, I will pay you for them” and walked away.

In 1870 Lobengula had moved his capital to Gibxhegu, and then renamed it koBulawayo and this was the site near where the Jesuits had established their mission station. [See the article; KoBulawayo, or Old Bulawayo (1870 – 1881) and the Indaba Tree] This was south of modern day Bulawayo, but in 1881 Lobengula burned down the old capital and relocates to a new capital, sometimes called Umhlabathini (a reference to the type of soil) or just koBulawayo. Physically this is sited where State House at modern Bulawayo now stands.

There is no evidence they were ever moved and when they were unearthed in 1910, they had probably remained at the original site at Gibxhegu since 1876, although nobody really knows.

Acknowledgements

W. Finaughty. The Recollections of an Elephant Hunter 1864 – 1875. Books of Rhodesia 1973

C.K. Cooke. Finaughty’s Cannon. Rhodesiana No. 33 September 1975