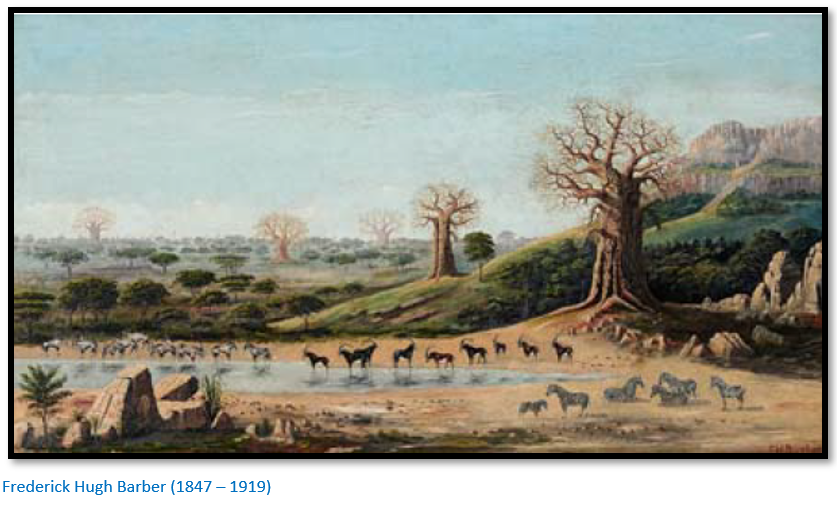

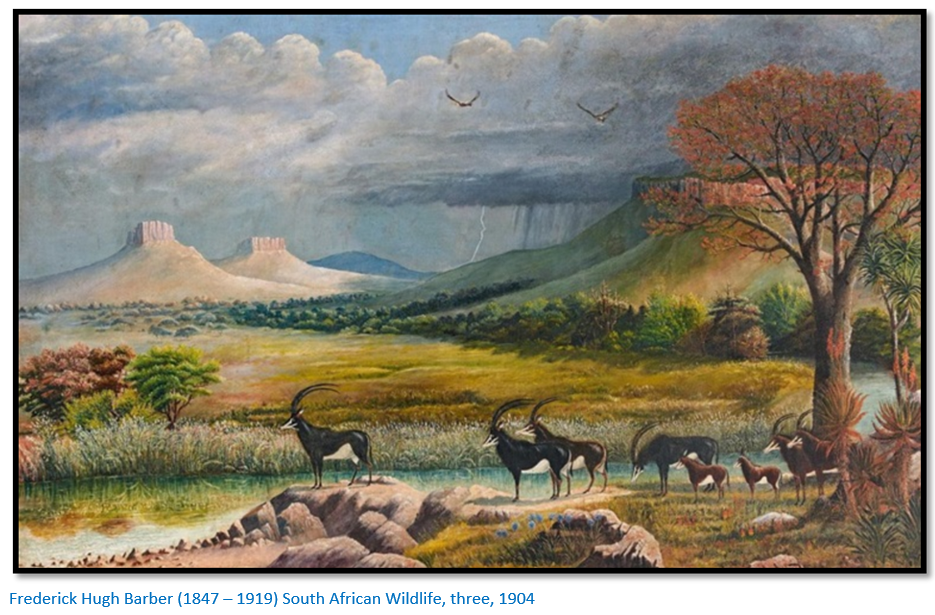

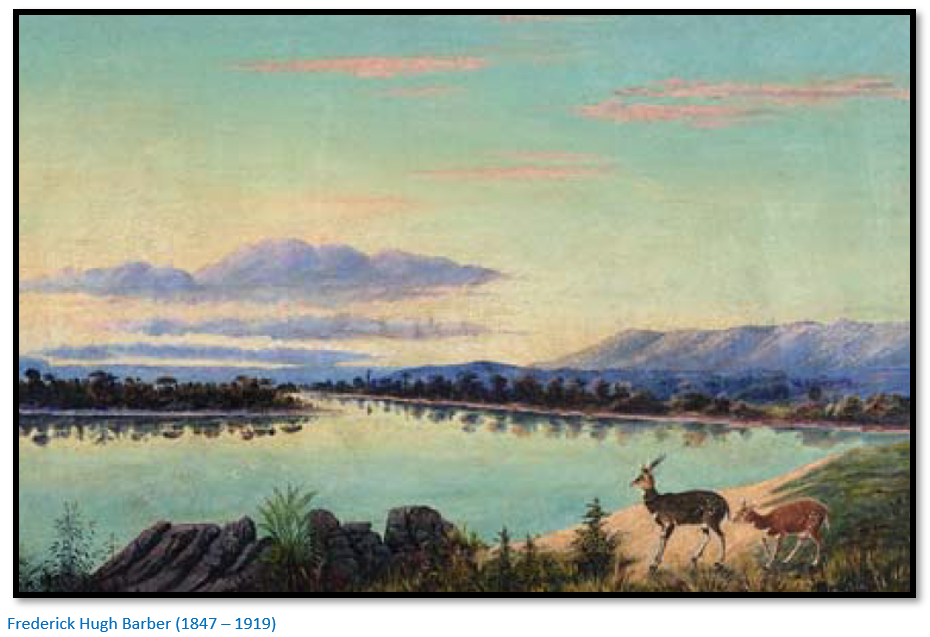

Frederick “Freddy” Hugh Barber, hunter, trader, artist – visited the Victoria Falls in 1875 and Matabeleland in 1877

The narrative is taken from the book Zambezia and Matabeleland in the Seventies published in 1960 by Chatto & Windus for the Rhodes-Livingstone Museum and edited by Edward C. Tabler, a well-known historian of the pre-pioneer period of Southern Rhodesian history, now Zimbabwe and is the first volume in the Robins Series in which he describes his 1875 trip toward the Zambesi River when he hunted elephant, buffalo, rhino, giraffe and numerous antelope. In 1877 he travelled into Matabeleland after more elephant and met King Lobengula.

The material before his journeys is from a number of sources – the most useful was Alan Cohen’s article: Mary Elizabeth Barber, some early South African Geologists and the discoveries of Diamonds which is mostly about his remarkable mother from whom he must have learnt the art of painting and the critical observation of the natural world about him. His paintings of the Victoria Falls are in the Rhodes-Livingstone Museum, which also published his travel stories: Zambezia and Matabeleland in the Seventies.

“Frederick Barber was a colonial hunter and the second artist of any competence to paint the Victoria Falls on the spot. [after Thomas Baines] Richard Frewen was an aristocratic English traveller and would-be explorer, who stirred up much trouble in Matabeleland and was responsible for worsening British-Matabele relations. The two journals are complementary and throw much new light on the decade 1871-80 in Southern Rhodesia, a period about which very little has hitherto been published.”[i]

His love of sport and the years spent in an ox-wagon, hunting, travelling and prospecting, brought him into contact with nearly every country south of the Zambezi, including Bamangwatoland, Matabeleland, Mashonaland, Bechuanaland, Manicaland, Gazaland, the Kalahari Desert, German West Africa (now Namibia) Zululand, Swaziland, Basutoland, the Transkei, and the Portuguese south coast colonies. He became a great friend of Chief Khama III of the bamaNgwato (Bamangwato) people of Botswana and spent three months on a friendly visit to Lobengula, King of the amaNdebele in 1877-1878.

Brief Details

Parents

Frederick William Barber (1813 – 1892)

Mary Elizabeth (née Bowker) (1818 – 1899)

Born: 8 January 1847 at Graaf-Reinet,[ii] on the farm Lammermoor in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa[iii]

Siblings:

Frederick “Freddy” Hugh Barber (1847 – 1919)

Henry “Hal” Mitford Barberton (1850 – 1920)

Mary Ellen Barber (1853 – 1938)

Married: 18 October 1898 at London England to Eira Rebecca Evans (1874 –?)

Children: Thomas Henry Rex Barber

Died: 19 May 1919 at Eldoret Kenya aged 72 years.

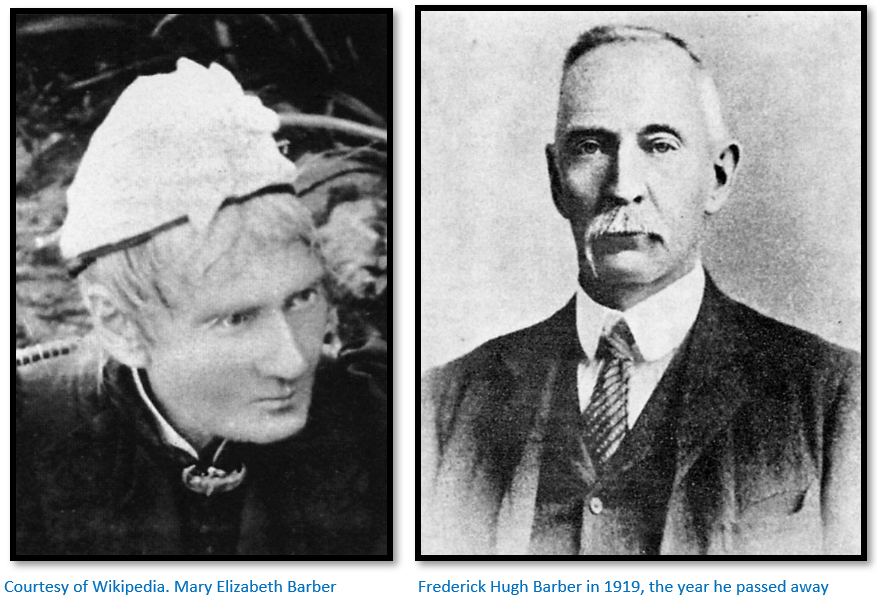

Family

Frederick “Freddy” Hugh Barber ranks with his younger brother, Henry “Hal” Mitford [he changed his surname to Barberton] as one of the pioneers of South African history. He was the son of Frederick William Barber, a geologist who had been studying analytical chemistry when his cousin Dr Guybon Atherstone persuaded him to raise sheep in the district of Grahamstown.[iv] His mother, Mary Elizabeth Barber, was the daughter of Miles Bowker, an 1820 Settler, and in her own right an authoress, scientist, naturalist and artist.

The author Tanya Hammel says of his mother: “As a child [Mary] Barber soon began to explore her environment. She is said to have been an autodidactic genius [self-learning] who taught herself to read and write when she was four. Her father set up a farm school for all his children and those of his employees. Her parents’ or teacher’s enthusiasm for botany, natural history and natural philosophy may indeed have been contagious.

She would ultimately paint more than one hundred watercolours of plants, butterflies, birds, reptiles and landscapes that remain to this day. Sixteen of her scientific articles as well as a volume of poems were published. To achieve the publication of her articles, she corresponded with some of the most distinguished British experts in her fields, such as the entomologist Roland Trimen, the botanists William Henry Harvey and Joseph Dalton Hooker and the ornithologist Edgar Leopold Layard. In doing so she contributed not only to botany but also to entomology, geology, archaeology and palaeontology. While her letters to these experts at the institutions they held an official position at have survived, their letters to her unfortunately have not…The tree aloe was eventually named Aloidendron barberae in her honour – one amongst at least ten botanical specimen, genera and butterfly species which were named after or ‘discovered’ by her.”[v]

She also had other interests in geology and prehistory and her eldest brother John Mitford Bowker was her early inspiration in ‘geologising’ as she put it. She wrote to him of the fossils they found near Graaf-Reinet: “We have found a good many fossil bones up here, but they are very much broken and the rocks that they are in are mortal hard. Fred found a pretty piece of a fossil fish with the colour of the scales beautifully preserved and they say that there is a large bed of fossil shells up in the Snew bergen but we have not seen any of them yet so I cannot tell you anything about them.”[vi]

Early Life

Born at Grahamstown, Freddy Barber grew up on his parents' farm at Graaf-Reinet in the Eastern Cape and was educated at St. Andrew College, Grahamstown. After leaving college, he launched out into various pursuits and enterprises, and his career has been one of singular experience and marked with considerable success. In 1898 Freddy married Miss Eira Evans, daughter of the late J.B. Evans of Rietfontein, Graaff Reinet, who introduced the Angora goat into South Africa.

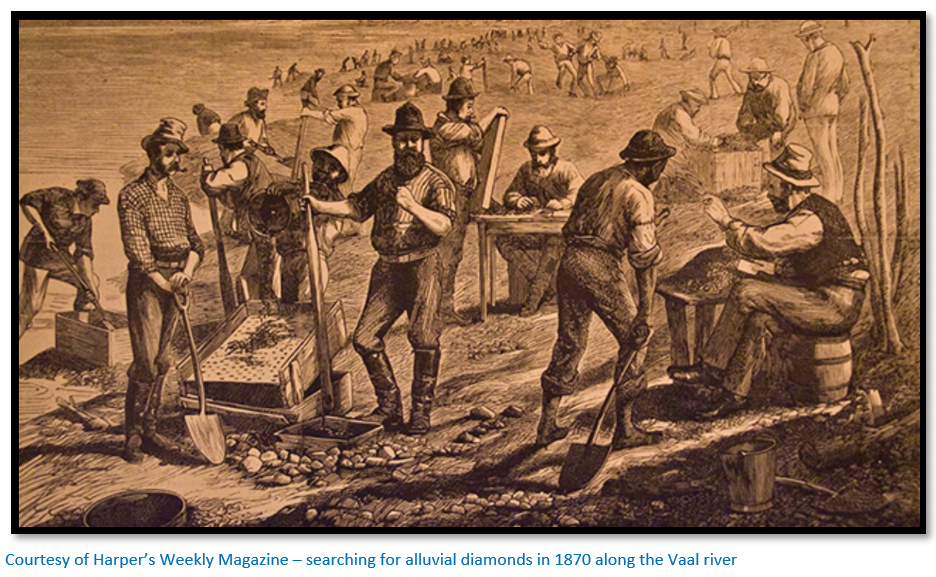

Diamonds digging on the Vaal river 1870

In 1867 Dr Guybon Atherstone was asked to test the first suspected diamond, the Eureka, with a polarising microscope. This rough diamond of 21.25 carats was found by a fifteen year old farmer’s son Erasmus Jacobs near the Orange river who gave the shiny pebble to his sister as a plaything. Later his mother gave it to a neighbour who when he sold it for £500 gave half to the Jacobs family; it is now at the Kimberley Mine Museum.[vii] The discovery was met with much scepticism, but in March 1869 a Griqua herdsman sold a magnificent pure white diamond weighing 83.5 carats to Schaleb van Niekirk for five hundred ewes, ten oxen and a horse. Van Niekirk sold it to Lilienfield Brothers of Hopetown for £11,200 who then resold it to Lord Dudley as the “Star of South Africa” for £30,000 and is now at the Natural History Museum.[viii]

The Barber’s along with almost everyone else yielded to the prospect of finding diamonds and Mary Barber wrote to Roland Trimen in June 1870 to say that ‘diamond fever’ had infected the region including her family: “You will be surprised to hear that Mr Barber and Freddy together with several other members of the family have started for the diamond fields ten days ago. Mr Barber is the head or “Gov’r” of the party – my brother Bertram Bowker with two of his sons have also gone and many others in this neighbourhood are preparing to go. It was not the newspaper reports which set our people “agoing” it was private letters from the diamond fields from relations of ours; letters of which there can be no doubt of their truth which caused them to go and when the newspaper reports commenced our people were all ready to start; the accounts which are received from our relations surpass those of the newspapers, the diggers or diamond seekers do not say much about their success and the newspapers only get half the news about diamond.

I never saw anyone so excited as Freddy was about diamonds, his sheep farming prospects were very good, but he at once let go one of his larger flocks and another Hal [his younger brother Henry] will look after, his angora goats too he let and his favourite breech loader gun he sold for a share in a diamond company which started about a month ago from kafirland. In fact the whole party went off in high spirits; very many other parties are preparing to go, it was not who will go, but who can go, for the houses and farms cannot be left alone. I must say I should like to go and have a look at that part of the world and seek new hoams [sic] and visits, etc. How jolly it would be, I have quite set my heart on going next spring, whether anything will “come of it” I cannot tell, I am afraid we cannot all leave home.”[ix]

In his memoirs Freddy said: “I recall the long dreary trek in a bullock wagon over the burning flats of the north Karoo…interspersed with memories of shooting and fishing by the way” until they reached the Vaal river: “where the rattle of carts and rocking of washing machines denoted the presence of the river digger in search of precious stones.”

The party consisted of Mary’s husband Frederick William Barber, their two sons Freddy and Hal, Charles Cumming (Atherstone’s sister Catherine’s brother-in-law) and a close friend Ernest Franklin. They worked the diggings for six months – first at Pniel, then at Gong-Gong and finally at Delport’s Hope: “like navvies with pick and shovel” and sold their diamonds for £1,000 a respectable price but not as much as they hoped for.

At least four other parties from the family were at the diggings. Gray Barber a nephew of Frederick, a cousin in Guybon’s brother John Atherstone, Henry Hutton and Alexander Cumming, both brothers-in-law, and one of Mary’s brothers, Bertram Bowker and two of his sons. Most of the diggers went home as poor as they started.[x] Frederick wrote to his brother Alfred: “It is a great mistake to suppose that they are to be had for the picking up. It is true that a man may be so lucky as to find a valuable stone as soon as he begins, but in ninety-nine cases out of a hundred it requires months of hard work to repay expenses, no-one ought to go to the diggings who has not the patience and pluck to work hard for months as well as the means for supporting himself and servants during the time he is there.”

The Barber men decided that summer was too hot to live under the rough conditions of the diamond fields and many diggers felt the same. The men were back on their farm Highlands at Christmas but by March 1871 Mary was writing to Roland Trimen that Freddy and Hal were preparing to start for the diamond fields again and that she was thinking of joining them: “not to remain there all the winter, but just for a trip to see the country and to amuse myself thereby…”[xi]

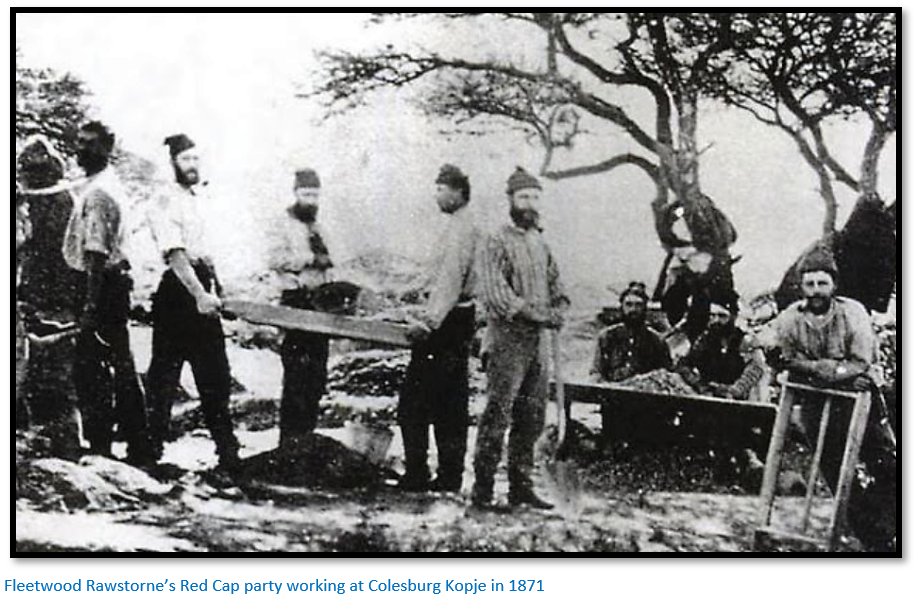

The Kimberley diggings 1871

In May 1871 the alluvial diamond diggings on the Vaal river were completely surpassed by the discovery of diamonds on Vooruitzigt farm owned by the de Beers brothers. They had bought the farm in 1861 for £50 and sold out in 1871 for £6,000 in what became known as the Old De Beer’s Rush.

Two months later on the same farm the extremely rich Colesburg kopje find was discovered which triggered the De Beer’s New Rush and eventually Kimberley.

Mary left with Freddy and Hal and daughter Mary leaving her husband Frederick at Highlands farm on 17 May 1871 and staked a claim at the centre of the De Beers mine joining her nephew Gray Barber at the diamond fields. One brother James Henry Bowker had arrived at Klipdrift the previous week in charge of a twenty-man patrol of the Frontier Armed and Mounted Police. Another brother Holden Bowker had been appointed Land Commissioner to arbitrate over the numerous claim disputes which were arising. Prior to the discovery of diamonds the area had been an empty space between the Transvaal Republic, the Orange Free State and Griqualand with not much interest shown in it. Now everyone wanted a slice, but by the end of the year the region had been included in the Cape Colony.

Mary was very much involved with the leading experts on the question of the origin of diamonds: her husband’s cousin Guybon Atherstone had identified the Eureka diamond, but her specialities were botanical, entomological and ornithological subjects, not geological and she wrote: “Depend upon it that the diamonds were not formed where they are now found…but by what means they have been transported, or from whence, I am not prepared to say. Let the geologists settle this difficult question…”[xii]

Mary had also been interested in prehistory since one of her brothers Thomas Holden Bowker in the 1850’s had made early discoveries of stone-age tools in South Africa and by 1880 Mary herself had one of the best collections in the country.

By 1879 the Barbers had lost interest in diamonds and Mary was back in Grahamstown ostrich farming as their feathers had become a fashion item. But she retained her interest in geology and the discoveries of coal in the Stormberg in the Eastern Cape and later in February 1884 of gold on Moodie’s farm in the De Kaap Valley of the Eastern Transvaal, now Mpumalanga excited her interest and probably encouraged her sons Freddy and Hal and their cousin Graham Hoare Barber to try their luck.

Police life 1872 - 5

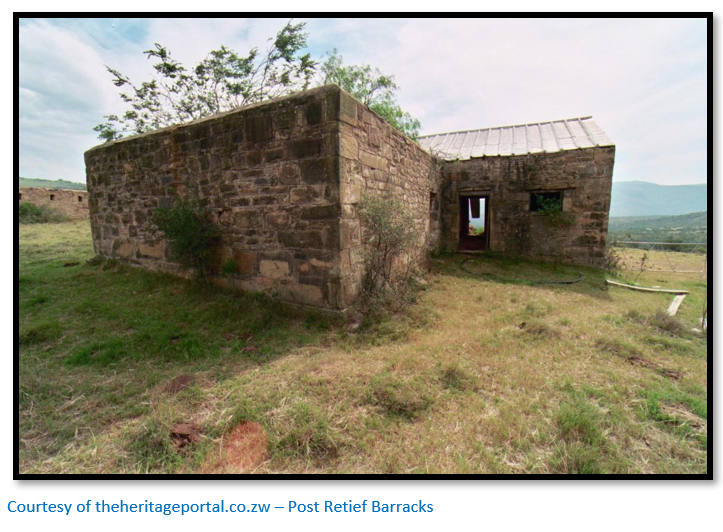

While digging diamonds with his father at Kimberley he was offered a commission as a sub-inspector by Sir Walter Currie in the Frontier Armed and Mounted Police which he accepted and was stationed for two and a half years at Post Retief near the Winterberg Mountains in the Eastern Cape.

His brother Hal wrote such interesting letters of his hunting experiences in the Northern Transvaal, now Limpopo that he decided he needed a break from the routine of police life; resigned his commission and returned to Kimberley.

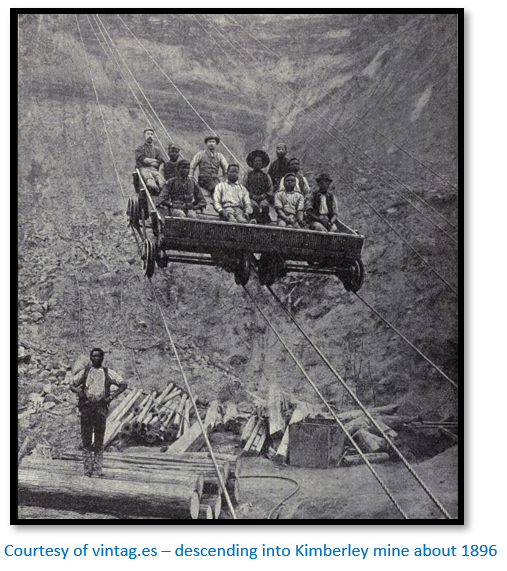

Kimberley had changed from the tented camp into a galvanised-iron town with a canteen at each street corner. The mine was now a vast hole with thousands of wire-ropes stretched from staging above in which stood tiers of windlasses. Leather and iron buckets ran on the wires hauling up loads of blue stone mixed with the soft crumbly, diamond-bearing gravel.

Here Freddy met an old friend W.A. “Zambezi” Browne who persuaded him to go on a hunting expedition into the far interior; they were joined by Levitt Frank, who contributed a wagon and span of oxen. They would shoot elephant until they reached the Victoria Falls and then come home with the ivory. As ostrich-farming was paying well they thought they might be able to collect ostriches around the Lake Ngami area and as money was not used in the interior they would pay by bartering their way with native trade goods including 8-bore muskets and powder,

Hunting and travelling 1875 - 6

They passed through Barkley West, formerly Klip drift and the site of the first diamond rush in 1870 on the north bank of the Vaal river and crossed the Harts river at Spalding’s canteen, before reaching Taungs where they visited the old Griqua chief Morikorane before moving onto the grasslands of Bechuanaland. Here was plentiful wildebeest, springbok, blesbok, pau and korhaan…all good eating.

The next town was Lichtenburg and soon after they were in the Marico district where Zeerust is the principal town and was formerly where the amaNdebele under Mzilikazi lived before being driven out by the Boers. They camped at Botha’s farm, but as he was the field cornet and as “Zambezi” Brown’s wagon was loaded with guns and powder that were considered contraband goods, he inspanned during the night and fled. In the morning Botha and his two sons smelt a rat and chased after the wagon but were unable to catch it.

Botha’s hospitality to Barber and Frank waned considerably on his return to his farm and they moved on to Fourie’s farm, the last house in the Transvaal and then they moved on and came across Brown at the junction of the Marico and Limpopo rivers. After congratulating Brown on his escape, he told them he had upset his wagon in his flight and had difficulty righting it and expected to be apprehended by Botha and his sons at any time.

In the bushveld region they travelled down the Crocodile river to its junction with the Ngotwane river enjoying the good hunting and from their camp under Kameeldoorn trees (commonly known as Acacia erioloba) moved on to Shoshong where they met Khama III Chief of the bamaNgwato (Bamangwato)

“Zambezi” Brown now left them to trade in Matabeleland and they were joined by George and Argent Kirton for the trek to the Victoria Falls. North of Shoshong they added D.J. ‘David’ Jacobs and his wife, a son of Pieter Jacobs, who lived a wandering life in the amaNdebele empire and Zambezia.[xiii]

They now encountered heavy sand which made trekking very hard on their oxen before they reached Lectautsi where there was water in a rocky canyon. Freddy’s description of the view from the ridge above the pool is worth quoting: “In the foreground the blue pool of water, the white-tented wagons, men, oxen, horses and dogs and the varied tints of autumn foliage. In the middle distance the dark flat-topped forest stretching away north, south, east and west into the grey haze of distance until lost in the far away dim horizon.

How a scene like this impresses one – the vastness and solitude of this mysterious limitless forest plain. Standing under a tree in the drowsy heat of an almost tropical sun, visions fill the mind and your immediate surroundings are forgotten. Beyond that grey, dim haze is the great Zambezi and its feathery, palm-timbered banks, islands and Mosi-oa-Tunya [the smoke that thunders] its mighty falls…”

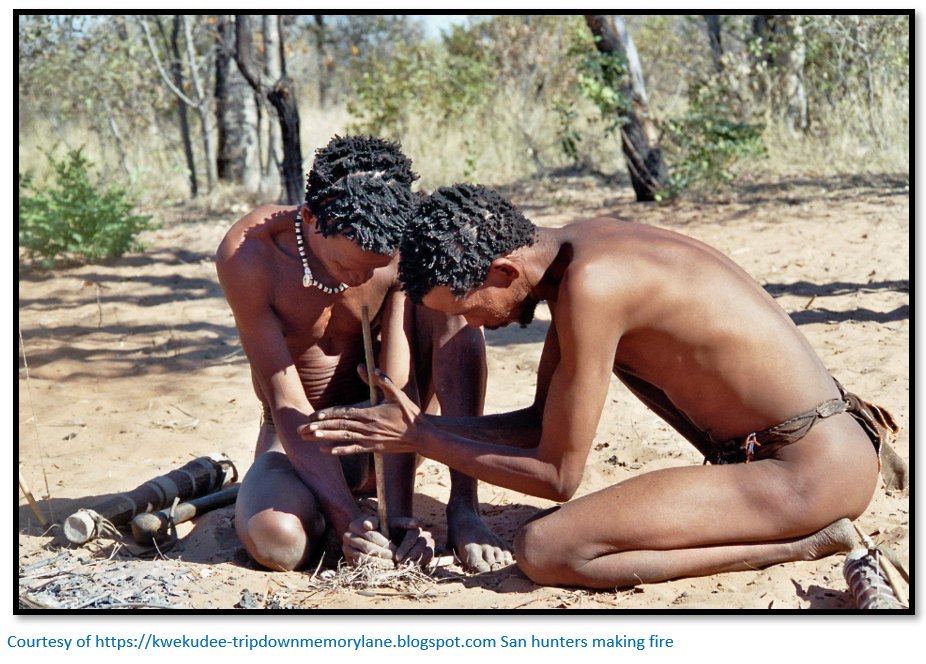

Now they trekked at night to Klabala where the water was raised in buckets for their oxen and a family of San hunter-gatherers put them on the track of eland which they followed and shot three and replenished their food stocks. Freddy remarks that for meat it is either feast or famine for these hunter-gatherers, at other times they existed on tortoises, berries, roots, mice and the bark of trees. Locusts were also a rare delicacy and they would follow locust swarms for long distances catching them when they settled at night.

From Klabala to Luali was another long night trek where again water had to be drawn by bucket from the sand-pit for the oxen. Another San group tracked giraffe spoor and after two hours they came across a herd of two hundred eland accompanied by three giraffe. Freddy galloped through the eland and shot a fine bull giraffe; the others bagged some eland.

The going was through heavy sand towards Marqua vleis and after twenty-four hours without water they met two of Khama’s men who wilfully misdirected them to a dry well. The oxen and horses were now exhausted. George Kirton thought there was water at the Marqua and took the most exhausted oxen and horses with him. Towards nightfall the remaining party at the wagons saw two San hunters approaching with a tin of water. Kirton had sent them back to assist in bringing on the party. All the oxen and horses were now sent on to Marqua before returning to bring on the wagons.

Once they reached Marqua they were approached by fifty bamaNgwato who told them Khama had forbidden people from camping at the site and they must turn back. The discussion became so heated that the party retreated to their wagons and armed themselves, but fortunately before matters got out of hand a sub-Chief arrived and said they could remain and camp as long as they did not shoot ostriches.

Between Marqua and the next waterhole at ‘The Mountain’ a bush fire swept down on them; there was just time to light a fire on the other side of the track and drive their wagons onto it as soon as the ground had cooled when they were surrounded by fire and nearly asphyxiated in the smoke.

They soon came upon the Nata river where it flowed into the Makarikari salt pan, now Makgadikgadi Pan. The pans were well-known for mirages – the party thought they had seen giraffe but when they followed them instead of getting closer they just faded away. Natives here were peeling up slabs of pink rock salt and carrying it away.

Some thirty kilometres up the Nata river the game was plentiful and they shot giraffe, oryx and ostrich. Here Freddy became lost in the bush for a whole day…fortunately he struck the dry-bed of the Nata river and followed its course and in the evening to his delight spotted their camp-fire.

Crossing the open plains to the north of the Nata river he shot an ostrich and they finally moved from the dry bush country and camped by a vlei in the shade of the mopane forest - the prior glowing reports from Brown and the Kirton’s now began to become more believable.

Trekking north they overtook an old Kimberley friend, Pat Wilkinson who joined the party at Gerufa whilst the Kirton brothers took their wagon east to trade at Pandamatenga along with the Jacobs’ and Karl Meyer, another hunter and trader.[xiv] August, a San hunter-gatherer spotted elephant tracks and quite soon after a low whistle from him warned the others he had spotted their quarry.

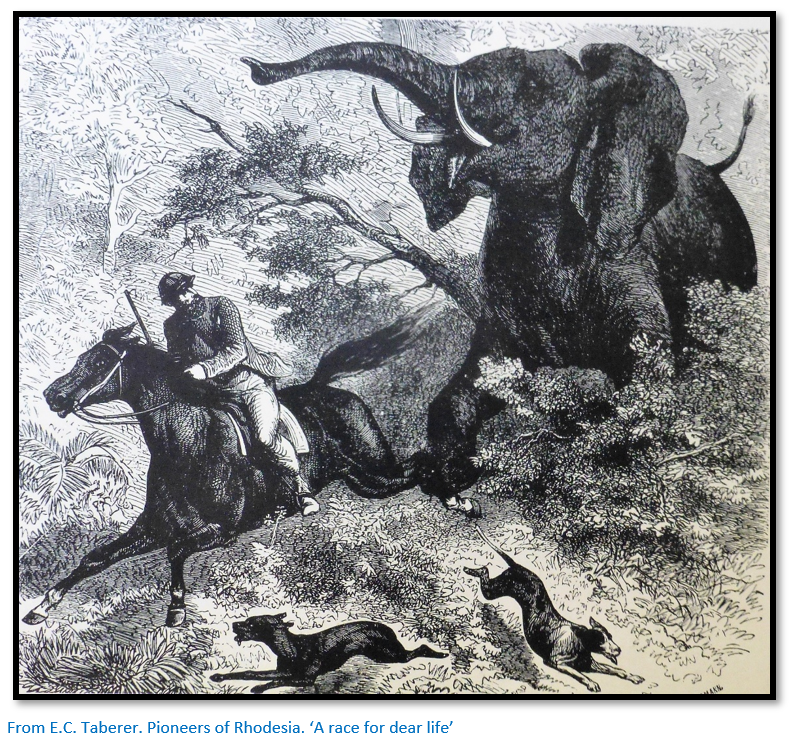

They drew up their horses to discuss the next move when suddenly the herd charged away, smashing everything in their path. Freddy drew his galloping horse level with the fleeing herd and fired at a cow with sizeable tusks and saw her fall at the first shot. He stopped to load a fresh bullet and powder and remounting dashed to what he thought was the head of the herd before suddenly becoming alarmed at a great clamour behind him and seeing a number of elephants charging down on him. He dug his spurs into the horse and finding after some minutes they were no longer in pursuit, turned back to the sound of the herd.

Soon after he fired at a large bull with good tusks which turned on him trumpeting shrilly and he was obliged to spur away to safety and reload. Chasing after the herd he was spotted by the same bull which turned and charged him again; a second shot into the middle of the chest brought the bull elephant down on his knees with his tusks embedded in the ground.

After much halloaing Wilkinson arrived hatless and stirrup less, his bridle was broken and much of his shirt was torn away. He had wounded a number of elephants which pursued him through the mopane trees so that he only escaped by the skin of his teeth. Although they followed the spoor of the wounded elephants they did not come across any of them.

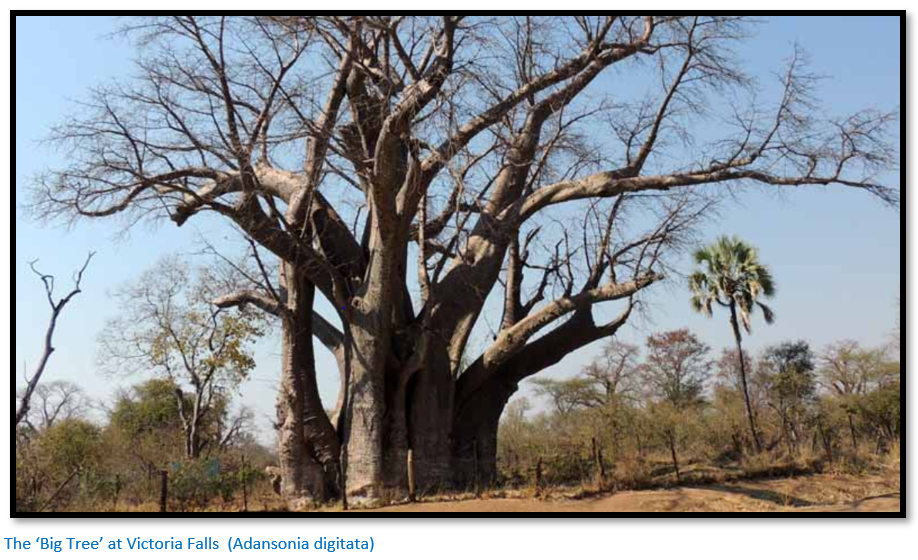

Continuing north they passed the “big baobab tree” known to many travellers because of its twenty-five metre girth and hollowed out centre which local people used for shelter.

At Pandamatenga[xv] were a number of traders with their wagons; one very ill with malaria who died and they were present at his funeral. Two other hunters and traders, Sandy Anderson and Alfred Cross joined them.

Beyond Pandamatenga was tsetse-fly country and the remaining one hundred kilometres had to be accomplished on foot; the six of them (Barber, Frank, Wilkinson, Anderson and Cross, plus Browne who had re-joined the party on 21 July 1875) set off with thirty native porters leaving the oxen and wagons in charge of the drivers. In the stillness of the second night they heard the distant roar of the Victoria Falls and a short walk at daylight brought them to the crest of a high ridge overlooking the Zambezi Valley and in the distance they could see the columns of white spray.

By noon they were on the banks of the Zambezi river and forcing their way through the dense underwood, monkey-ropes, tree-ferns and climbing plants that grew in the tropical heat and heavy spray and on pushing through this undergrowth found themselves on the opposite edge of the narrow chasm over which the river leaps as a white wall of falling water.

In the afternoon after hours of viewing they felt tired and hungry and pitched camp beside a large baobab, a short distance above the falls. Below a photo of the largest baobab, nearly two kilometres above the Victoria Falls on the southern bank within Zimbabwe and accessed on the Zambezi river drive; it is the most likely candidate for their campsite as it was known as a rendezvous for early travellers.

During their remaining days Freddy made several sketches of the Falls with its ever changing spray cloud and the remarkable vegetation from which he produced some fine paintings some of which are at the Livingstone Museum in Zambia.

The party of six were joined here by Alexander Deans and Matthew Clarkson; on their way back to Pandamatenga a herd of buffalo swept through their native porters who managed to escape by climbing the mopane trees.

Close to Tamafupa pan on the road cut by George Westbeech in 1871[xvi] Freddy was charged by a buffalo he had wounded which fell dead just a few metres from him. A few days later after spending most of the day tracking an elephant he was on the point of giving up the chase when he came across it under a tree. As the elephant raised its trunk Freddy fired into its chest and through the powder smoke he saw it charging him. He says: “To bound into the saddle was the work of a second and to get well under way about as much more. I wasn’t a bit tired. I could have kept an appointment punctually a mile off in less than a minute. August and the two other boys had disappeared and I was disappearing also when the elephant plunged forward on his head and fell over dead.”

Very pleased with himself he returned to camp to find Wilkinson had shot four elephants during his absence!

W.A. Browne ‘Zambezi Browne’ at this camp had £180 and a gun stolen by a servant named Harry who fled south. Barber and Browne tracked Harry for two days and found him resting by a bush after the sun glinted from the gun barrel. He was pounced upon and after being bound given twenty-five lashes with a sjambok before being marched back to camp. At camp a judge and jury were appointed and Harry sentenced to be hanged. Wailing and shouting for mercy, a rope was placed around his neck and after being partially hung he was thrashed again and told to clear out of the camp and told if seen again he would be shot on sight.

The expedition reached Kimberley in January 1876 shooting only one more elephant having been away for nearly a year. The rest of the year he spent diamond digging working ground on tribute. He says when in a rich seam it was sent to the owner; when in poor to the tributary’s, but it was an irksome life for someone of his wandering habits and restless spirit.

A Hunting expedition to Matabeleland in 1877

Freddy and Hal Barber left Kimberley on 27 February 1877 with a quantity of trade goods to barter with the natives of the interior for ivory and ostrich chicks and crossed the Vaal river at Klip Drift, now Barkley West and trekked to Shoshong where they were kindly received by Khama III. However he would not allow them to capture wild ostrich chicks at Lake Ngami, saying that as there were so few elephants left in his country, this was the only source of revenue left to him: so they abandoned this project and headed for Matabeleland.

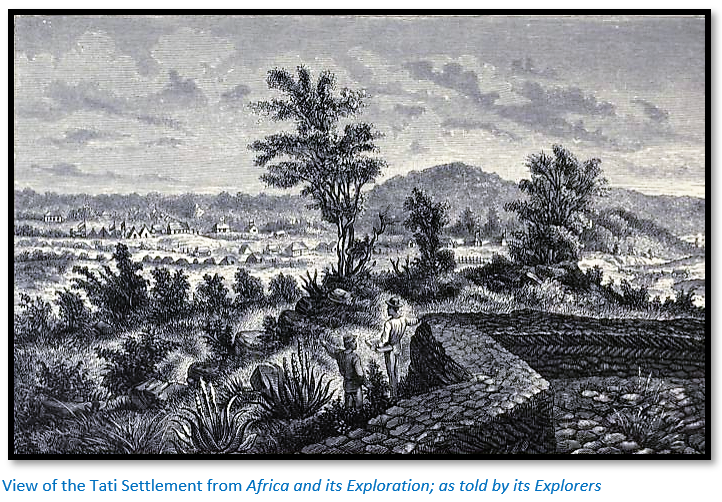

Khama had forbidden the sale of liquor within his territory and several traders were fined or expelled for selling it. The brothers had two half-aums[xvii] of brandy which Khama spotted and enquired about what was in the casks. “Oh, just brandy” I answered. “What are you going to do with it?” “Sell it to your friends the Matibeli” (sic) actually his greatest enemies. This caused great merriment. Said he: “Well, don’t sell it to my people.” “Never fear Chief” I answered, “we are going to drink it all ourselves.” Great laughter. They reached the Tati gold field[xviii] and viewed the old ‘Blue Jacket’ gold mine where local people were being troubled by lions.

John Lee and his family were away from his farm near Mangwe Pass and hunting, so they camped on the banks of the Ingwesi river, the frontier from where the headman sent runners to Gubulawayo to request permission to enter amaNdebele country. When this was received they trekked on - arriving at Gubulawayo on 20 May where they camped by Clarkson and Goulding’s store and found stores and houses belonging to George Westbeech, George “elephant” Phillips, Henry Ogden, Catonby, Petersen and Deans and waited for Lobengula’s return from a small kraal on the Amatsheumhlope “White Stones” stream.

It was the traders and hunter’s custom to proceed to the King’s location, report themselves, exchange greetings and give the King their presents, eat meat and drink beer and make friends, after which they were free to come and go to the King’s court.

Matthew Clarkson took the Barber brothers to the King who they found laughing and talking with about forty of his bodyguard and watching the women planting maize. He greeted them cordially and asked whether they were traders or hunters.

He invited them to drink beer and eat and as he walked along with his bodyguard they “could not but admire his dignified carriage, powerful build and massive limbs. Around his waist was a great apron of cat and monkey tails, completely encircling his loins, and bar sunshine and a few ivory rings and brass armlets, this was his only attire. His hair was worked up into an apex, surrounded by an oily, shining ring or ‘seketla.’ He had a pleasant face, a ready wit, and loved a joke – a great savage and a fit ruler for the savage hordes over whom he held sway. At this date he must have been about forty years of age and on his cheek was a large scar received from the gun of Chief Khama when Lobengula attacked Shoshong.”[xix]

On hearing they wanted to shoot elephants Lobengula said they must return to Gubulawayo and stay at Umvutcha, the “white man’s camp” about a kilometre from his kraal where they mixed with the other European traders.

Next day Lobengula paid a visit to their wagons wearing not his usual cat and monkey tails but a complete brown moleskin suit, his feet wearing Wellington boots and his head with a brown ‘wide-awake’ hat.[xx] The goods they had brought were off-loaded from the wagon for him. He tried out some of their guns and made some good shots. There were a couple of dozen yellow-striped blankets which the King purchased for his wives paying in ivory, of which he had two huts full.

When the King visited their camp he was seated on two cases of whisky covered with a blanket as none of the camp chairs would carry his weight. When he was offered condensed milk he preferred a tin from which the others were served, rather than a new one, as he knew it would not contain poison. After eating with them he was presented with a nickel-plated revolver and a sliver mug with glass bottom which pleased him.

To obtain permission to shoot elephants it was customary to give Lobengula a present. Hal gave the King a salted horse which had cost £95[xxi] and Freddy gave him eight Enfield rifles which had cost about £40. The King delayed giving permission for two months before asking them to accompany him to Umganen, the King’s garden. They visited the King daily and were kept well-supplied with beef and mutton.

On one occasion the Barbers and Clarkson and Goulding were having a nightcap when a dozen young warriors ‘majakas’ walked in and stole some items from the wagon. Next day this was reported to the King who sent for the inDuna and told him to tell the young men to return the white men’s things. The King was told the white men lied and when the King made a second request the same reply was made. Lobengula arose, snatched up a large rhinoceros-horn knobkerrie and walked into his bodyguard’s enclosure. A general rush was made for the fence around the enclosure and Lobengula hurled his heavy knobkerrie which knocked a warrior senseless to the ground. Calling for his knobkerrie to be returned, Lobengula climbed back on the box of his wagon and loading a Martini-Henry rifle roared out that he would start shooting indiscriminately unless the stolen goods were returned.

In a moment a kaross, a box of percussion caps, a bag of bullets, two American axes and several other items were returned. The King was praised by a crowd which had gathered and he told them he had witnessed the scene from the entrance to his enclosure the night before. Turning to the Barber brothers he said: “There, white men, are your things. Make a fence around your wagons and shoot anybody that comes in at night. It is only wolves that run about at night.” The brothers asked the King to spare the felled warrior.

When they asked if they could go hunting the King replied: “Oh you can go if you like. But what is your hurry? Are you not enjoying yourselves with me? You have not half paid me a visit yet. There is still lots of fat meat and beer.”

At last they were granted permission to hunt elephant in the northwest. On Sunday 3 June they were up early and inspanned, only waiting or Lobengula to get up, to say goodbye to him. He soon made his appearance, wished them a successful hunt and gave them a fat sheep to provide meat until they were amongst the game. After a long tiring journey they made their base camp in the Linquasi valley[xxii] along with Fred and Spencer Drake, Solomon Vermaak and his wife and Willie Brown. Leaving their wagon here they set off on foot with Fred Drake in the direction of the Gwaai river, over two days journey away which they reached on 16 June 1877. The following is from Freddy’s journal: “For some distance we kept along a well-beaten game track leading from the water, then turned into the bush which was very thick. The spoor was difficult to follow and we lost it.

We then separated, my brother to the left and myself to the right. We were about eighty yards apart when I heard a rush of some large animal in front of me. Snatching my heavy rifle from my gun-bearer I ran forward to get a shot. At the next instant I heard a terrible cry which I knew was my brother’s voice. I rushed frantically towards him and came upon him in an open space, lying where he had fallen. He had only time to say that he had been tossed by a buffalo when he went off into a dead faint.

I dragged him into the shade of a tree and examined his wounds. A fearful gash eight inches long appeared almost to sever his leg from his body. The horn had penetrated the thigh at the fork in front, below the abdomen and passing clean through and out behind where there was another gash three inches long. He was covered with dust and blood and the stock of his heavy rifle was broken at the hand-grip.

An old buffalo bull, probably a rogue that had been driven out of the troop by young bulls, had charged from the thick bush, so suddenly that he only had time to grasp his heavy rifle from the gun-bearer, when the buffalo was upon him. In trying to jump out of the way, he had tripped over a dry branch and while falling forward the buffalo had struck him, picked him up and swung him several times around his head; tossed him into the air and galloped off.”

Freddy managed to get Hal back to their camp at least ten kilometres away with a litter of branches, but he was left injured for several months during which time he was nursed by Freddy. Their camp was only one hundred metres from a waterhole and as Hal could not be moved they were continually troubled with lions who made the nights hideous with their roaring.

On day a Mr Sell wandered into their camp[xxiii] and looked after Hal so that Freddy could go down to the wagons on the Linquasi, a hundred kilometres away. Only one of their horses had survived the horse-sickness and after another month of convalescence Hal was well enough to be carried back on a litter on the shoulders of their strongest servants.

Whilst marching along a narrow path they heard a great rush of buffalo; the litter and Hal were dropped whilst everyone except Fred climbed trees. Fred fired a fusillade of shots into the bush which caused the herd to swerve to the left of the party and into the bush.

Next day the litter and Hal were dropped again when they came upon a small impi of thirty amaNdebele warriors with shields and assegais on the path headed by their induna. They squatted around Hal and the litter and were told the story of the misadventure before moving on after promising not to harass their Makalanga servants.

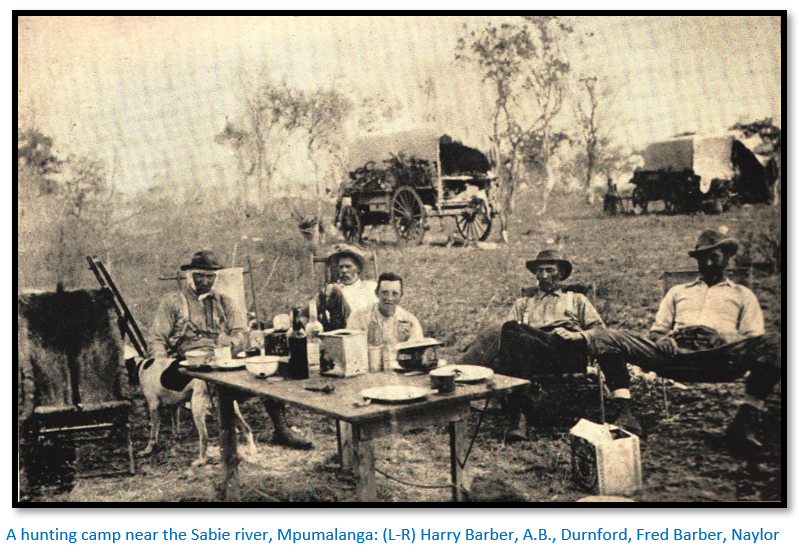

Jack Goulden was at the camp along with some of the Dutch women who promised to look after Hal whilst Fred went hunting with the Drake brothers. During the next two months they shot fifty-one elephants; Fred Drake heading the list with seventeen. There are numerous tales of hunting elephant and close shaves in the thick bush. On one occasion Fred Drake and Fred Barber were following the spoor of a bull elephant which had become indistinct. Drake dismounted and was looking for the spoor and they did not notice the elephant a few metres away in the dappled shade until it charged them. Drake made a bound for the saddle; Barber fired at the elephant over Drake’s back which fell dead within a few feet of them both. This was another near thing and a reminder of how dangerous a hunter’s life could be.

Hal was now able to hobble around on crutches and so from the Nata river Jack Goulden, the Drake brothers, Vermaak and the Barbers travelled down to Gubulawayo arriving in mid-December 1877.

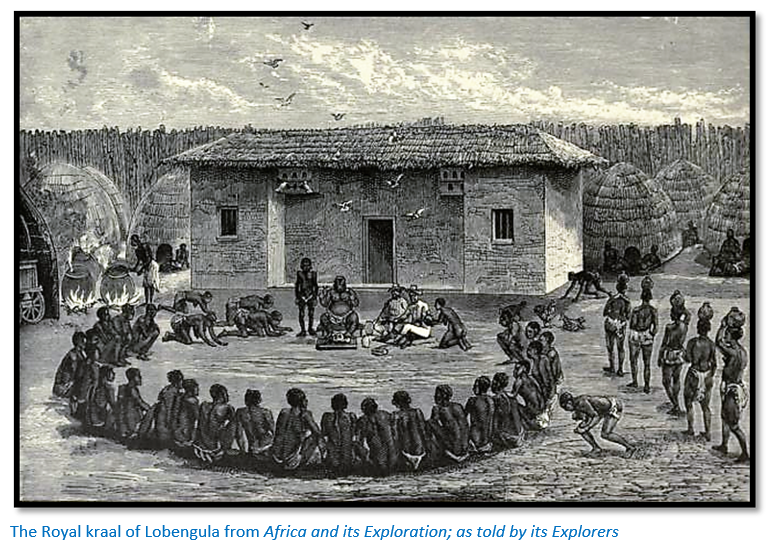

Gubulawayo

The kraal was about five hundred and fifty metres across, in the centre the sekatla a circular stockade of high poles which enclosed the King’s residence, a red brick European-style house.[xxiv] Fred says that the brick house was only a show-place where Lobengula kept his guns and rifles, occasionally he sat on a large cushioned horse-hair armchair on the verandah, but generally he preferred his wagon-box from which he entertained visitors and dispensed justice. Around the seketla was an open space where dances and festivals were held and outside this was the circle of huts where the people lived. In all there were about three thousand inhabitants at Gubulawayo.

“It is a circular-shaped town situated on the apex of a smooth, dome-shaped hill sloping gently away on all sides and surrounded by hills and wooded valleys. In the vicinity all the wood and bush had been cleared for building huts, firewood and clearing for lands.”[xxv]

“Within a radius of twenty-five to thirty kilometres are the King’s cattle stations where he often spends weeks of his time. As soon as he is tired of one place, he inspans his wagons, one of which was filled with ivory and moves from cattle post to cattle post accompanied by his court and bodyguard. The cattle are divided among the posts or stations according to colour. At one station are the red, at another the black and so on. Each herd is in the charge of the inDuna (headman) of the town. All the cattle in the country are the King’s and no beast is killed without his permission.”[xxvi]

“Every affair of the nation is reported to him by messengers. He is the chief magistrate and gives judgement without hesitation in all matters of life or death. What the King says is final and there is nothing more to be said. Small matters are left to the indunas of the kraals. Great political cases are discussed by meetings of the indunas and headmen who sit in debate for days sometimes. Each one has his say, the King listens and when the subject has been thoroughly threshed out, gives his judgement. Cattle are killed, beer handed round and everybody praises the wisdom of the King who sits on his wagon box in front of his travelling wagon, cracks jokes, spins yarns, and the King retires to sleep, the people disburse to their homes with loud shouts and praises for the King.”

When the rainy season set in, the hunters settled down and made themselves comfortable to watch the great dances and ceremonies that were held annually to mark the ripening of the crops.

“At Bulawayo the traders have built a number of houses and stores and there are about fifteen or twenty whites living there always. The elephant and other hunters collect here in the beginning and in the end of the season. Permission to hunt must be procured from the King before you can enter the hunting veld. The hunting season commences as soon as the worst of the fever season is over at the end of April and the general ruck of hunters get back about November, at which time the weather becomes hot and the rainy season sets in. The hunters disperse to their different homes in the Transvaal, Kimberley, etc. Many stay in Bulawayo, where they sell their produce of ivory, [ostrich] feathers, skins, etc. The majority of the hunters are Boers, and traders English.”

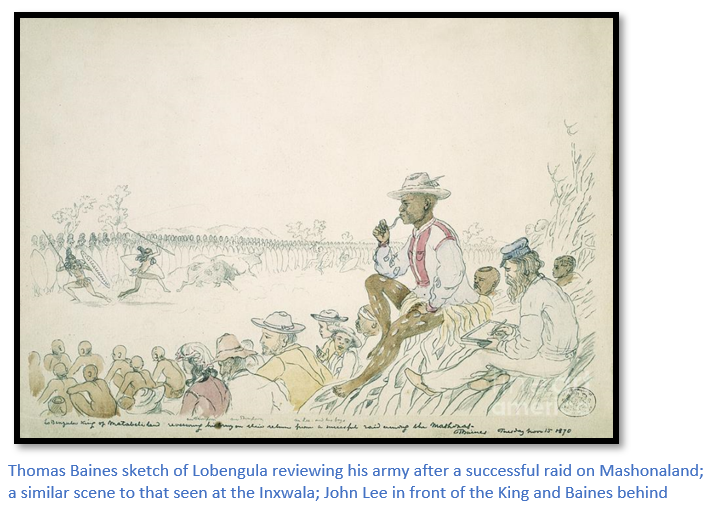

The Inxwala

The dance of the first fruits was a magnificent sight with seven or eight thousand warriors, each regiment in the charge of an InDuna and distinguished by the different colours of their shields of cow-hide. As they chanted their songs they struck their shields with their assegais, while distinguished warriors would bound forward from the ranks and springing in the air, stab and thrust as if in desperate combat, each thrust signifying a man they had killed. “Sometimes in his excitement a man would make too many stabs and be greeted with howls and shouts of derision from his companions for lying (when he would retire crestfallen to the ranks)”

Fred Barber says it was wonderful to see these thousands of soldiers, rank after rank of waving plumes as they moved in perfect time, the thud of their feet making the ground tremble, while their shouts could be heard for miles.

The dance was held annually just after the ripening of the new crops, usually in January. Tabler says it was a religious ceremony to calm the ancestral spirits of the King and a subtle renewal of national loyalties.[xxvii]

Fred estimated about thirty white men were present in January 1877 and after the Inxwala they returned to Lobengula’s kraal; “the King’s beer was the best in the land and he was liberal with it and good humoured, he was much appreciated and the beer and it was a good opportunity to get posted in the habits and customs of these [amaNdebele] people.”[xxviii]

Richard Frewen’s threats and bad behaviour[xxix]

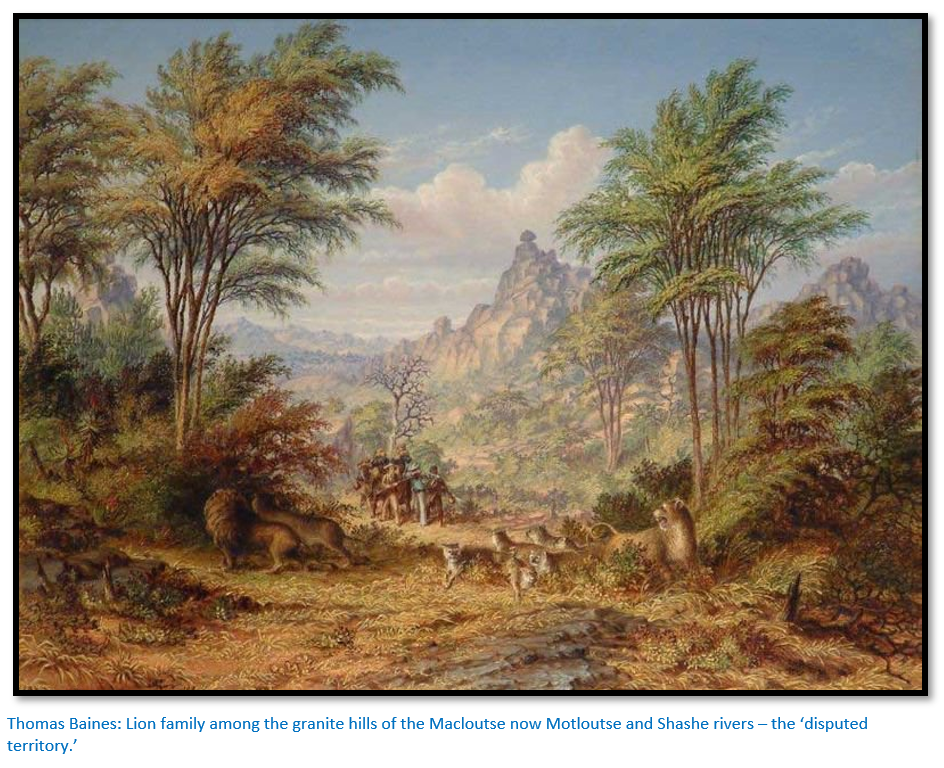

Fred states that Frewen had strayed from Khama into Lobengula’s territory “the disputed territory” between the Motloutse and Shashe rivers and the amaNdebele had seized his muskets and taken them to Gubulawayo. This is incorrect and the true version of events is included in the article on Richard Frewen.

However Frewen did come to Lobengula as he wished to stay in Matabeleland during the summer rains and explore north of the Zambezi river the following year. He handed over a letter of introduction from the Governor of the Cape Colony, Sir Henry Bartle Frere and informed Lobengula that he was a great chief and would not stand this nonsense; threatening to return with an army and “eat Lobengula up.” He then returned to his wagon and dressed in his volunteer’s uniform and hoisted the Union Jack!

This ridiculous behaviour only annoyed Lobengula and Frewen was told to clear off and to bring his army back at once. The immediate consequence was that the traders and hunters at Gubulawayo found that Lobengula’s displeasure resulted in a change of manner; there was no more meat and beer and they were frequently asked when they expected their great white chief and his army to arrive!

When they made preparations to go and went to say farewell to Lobengula, he refused to let them go saying he intended keeping them as hostages. As there seemed little they could do Freddy and Mathew Clarkson, leaving Hal who still on crutches, went on a riding tour visiting Shiloh mission under the Revd. Thomas, then Inyathi mission under Revd. Sykes and then to George Wood’s hunting camp where “we drank much coffee and smoked many pipes and swapped many hunting lies” before returning to Bulawayo and finding the King as grumpy as before.

Fred had a scotch cart to sell, so loading it with trade good and muskets, he and Hal went to Shiloh mission where in a week’s trading they returned with over 200 kgs of ivory.

On their return they heard the King was in a better mood and rode over to see him at Umganen where they had a meal of roast ox and beer and the King told them his heart had softened and they were free to leave his country. They bid the King farewell and went back to Umvutcha to prepare their wagons for the long journey back to Kimberley.

They set off back to Kimberley in January 1878 travelling with Mathew Clarkson and Robertson, who had been Frewen’s trek manager. The rivers were in flood and Freddy saved Robertson from drowning in the Ingwesi river.

Hal needed to go down to Cape Town for medical treatment and for the rest of his life always walked with a limp.

Diamond-mining and farming 1878 - 84

In 1879 Fred returned and worked claims on the Kimberley mine with some success and the following year he went to the Fish river and farmed ostriches at ‘Junction Drift’ near Carlisle Bridge until 1884.[xxx]

Gold-mining at Barberton 1884 - 86

In February 1884 they heard that a rich gold reef had been discovered on Moodie’s farm in the De Kaap Valley in the Eastern Transvaal, now Mpumalanga. Freddy and Hal and their cousin Graham Hoare Barber, Holden and Edward White all travelled to this locality where they hoped to make their fortunes as miners and diggers. Gold had been discovered in 1882 in a small creek running through the town of Duiwels Kantoor (the Devil’s Office) later named Kaapsehoop. This led to a portion of the original township layout being cancelled and opened up for gold diggings. Further gold discoveries were made at Pilgrim’s Rest in 1883.

Freddy out prospecting found a quartz reef running up the hillside of a steep mountain spur that after crushing and panning was found to contain payable gold. Next morning they pegged the reef and moved camp to the base of the hill which ultimately became the town of Barberton. News of their discovery brought in many other prospectors and a number of other reefs were pegged, including the Sheba reef and the Kimberley Imperial reef. The settlement that grew up with its canteens, shops and a post office was initially called Barber’s camp.

They were not the first to discover gold in the Barberton area; Tom McLachlan found alluvial gold in 1881 but the lowveld had endemic malaria and prospectors kept clear until Auguste Roberts “French Bob” found gold in Concession Creek in 1883 which resulted in a gold rush.

In June 1884, Graham Hoare Barber wrote a letter to the State Secretary to inform him that he and his two cousins Fred and Harry had discovered payable gold on state land where the Umvoti Creek entered the De Kaap valley. The State Secretary then asked the Magistrate in Lydenburg to investigate the matter and for the Gold Commissioner David Wilson to submit a report.

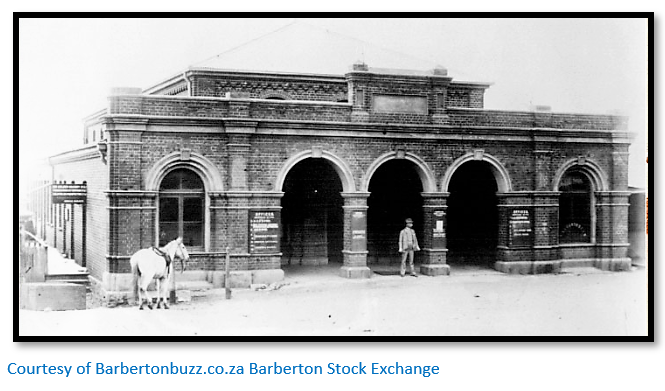

In July Wilson confirmed the gold claims and on 24 July 1884 named the simple mining camp Barberton after its discoverers, the Barber brothers and their cousin.[xxxi] The settlement grew quickly when Edwin Bray, a prospector, discovered gold in the hills above Barberton in 1885 and with fourteen partners started the Sheba Reef Gold Mining Company. Large amounts of money flowed into Barberton and the first Stock Exchange to operate in the then Transvaal opened its doors.[xxxii] A boom followed with billiard saloons and music halls being established, the Criterion and Royal Standard hotels opened and in 1896, Barberton was connected by rail with a branch line running from Kaapmuiden to Barberton.

The plaque on the Stock Exchange building reads: “This building dating to 1887 originally housed the first Stock Exchange in the Transvaal registered on November 23, 1886 as ‘The Kaap Gold Fields Stock Exchange Ltd.’ Historical Monuments Commission. The plaque was presented by the Johannesburg Stock Exchange.

The original reef discovered by Fred and Hal was floated into a company and a ten-stamp battery erected and the first crushing of one hundred tons of ore gave five ounces to the ton, but the reef pinched out and the company amalgamated with the Sheba.

Barberton flourished for only a brief period and soon most of the inhabitants, along with the Barber brothers, began to move away to the newly discovered gold fields on the Witwatersrand, although some mining continues to the present day.

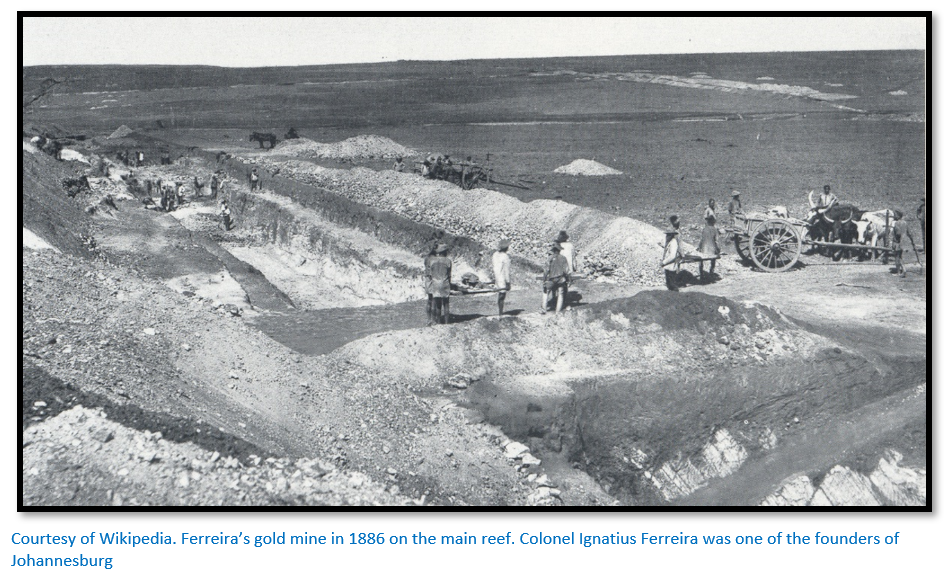

Gold-mining on the Witwatersrand 1886 - 89

Freddy Barber travelled to the Witwatersrand goldfields and settled in Ferreira's Camp (now Johannesburg) a long rambling collection of tents, wagons and corrugated-iron shacks extending along the reef for many miles. They purchased claims from Col. Ferreira and sank the first shaft on the Rand to a depth of 50 feet, thereby proving the permanency of the reef, and crushed 100 tons of ore at Struben's mill, which yielded over one oz. to the ton over the plates, the ore being carried by bullock wagon for nine miles. Following this they floated almost the first company on the Rand, the "Ferreira", with a capital of twelve thousand pounds.

First known as Ferreira's Camp and later Ferreira's Township, it is the oldest part of Johannesburg. Sometimes referred to as the "cradle of Johannesburg", it is where the first gold diggings started, and where the first diggers initially settled. The city grew around the mining camp in the Ferreirasdorp area and Johannesburg’s Main Street developed from a rough track where the present Albert Street led off towards Ferreira’s Camp.

Later Freddy Barber floated the Simmer and Jack Gold Mining Company and acted as director and promoter of some of the principal gold mining companies on the Rand, including the Jumpers, Aurora, Spes Bona, Kleinfontein, Princess and Nigel Deep. He was also associated with the flotation of the Transvaal and Delagoa Bay Investment Company and the Johannesburg Board of Executors, in both of which he was a director. Their knowledge of gold-mining and trading on the stock exchange brought much success.

Later life

After this successful spell in the financial world Freddy returned to farm in the Eastern Cape, also becoming active in civic affairs (he was asked to be Mayor of Grahamstown twice, but declined)[xxxiii] the Grahamstown Municipality, the local arts association and the botanical garden. He farmed sheep at “Green Hills” near Grahamstown until 1910 when he sold and moved to Rosmead where he farmed ostriches at “Hiltondale”

His brother had moved to Kenya and in 1915 Freddy sold up and moved close to his brother buying two farms at Eldoret and another at Elgon near his brother’s farm “Caverndale.” He lived in Eldoret with his wife Eira and only son Rex. He died on the 19 May 1919 and is buried at Eldoret cemetery.

Above Fred and Henry Barber’s grave with its two marble panels. On one side the Barber crest and arms are carved with the following inscription: To the Glory of God and in loving memory of:

Frederick Hugh Barber, F.R.G.S.

Born 8th Jan 1847. Died 17th May 1919.

Henry Mitford Barberton, F.R.G.S.

Born 7th Sept 1850. Died 25th May 1920.

Sons of F.W. Barber of S.A.

The second marble panel reads: These hardy pioneers blazed many a trail into the wilds: they were brave hunters and friends of all men. They founded Barberton in 1884 and were leading pioneers in Kimberley and Johannesburg. England were not England were her sons other than these.

Other achievements

Freddy was a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society and in 1897 was a member of the Geological Society of South Africa and on the Committees of the Grahamstown Museum, Art Society, and Botanical Gardens; and a J.P. of Albany. He was late Chairman of the Board of Works, Municipal Council, Grahamstown. He belonged to the following clubs : Rand and Pioneer, Johannesburg; Albany and Grahamstown Clubs, Grahamstown; and the City Club, Cape Town.

Primarily a hunter, prospector and explorer, Freddy also had an interest in natural history and geography, though his contributions to these fields were modest. As a young man he collected butterflies and in 1876 sent a consignment from the Crocodile River and the country northwards to the Zambesi (now Zimbabwe) to Roland Trimen at the South African Museum. Trimen later acknowledged these donations in the preface to his book on South African butterflies. Freddy and Hal also collected plants on their travels and sent some to Kew Gardens. Freddy's main interest, however, was in the larger mammals and he built up a very fine collection of heads and horns. Part or all of this collection, described as "a fine collection of mounted heads of East African antelopes" was exhibited in the Albany Museum in 1897. It was probably only on loan, for he eventually sold his collection to the New Zealand Zoological Society in 1909.[xxxiv]

Epilogue

This brief summary of his important and useful life has been little short of cataloguing the main events of his career. His life was many-sided, comprising as it did that of farmer, frontier policeman, explorer, hunter, miner, prospector and speculator. His expeditions extended into almost every remote part of Central South Africa and the colonies, while on the Continent they have included nearly every country in Europe, besides visiting Egypt and travelling up the Nile. A man of culture and refinement that in no way have deteriorated from the rougher influences of life, he figures prominently among the leading men who have aided in the promotion and extension of South African interests. His enthusiasm and love of sport, natural history, and enterprise is characterised by self-restraint, probably due to his excellent home training. Throughout his career he has shown a singular recognition of the higher ideals of life.[xxxv]

References

Africa and its Exploration; as told by its Explorers. Sampson Low, Marston and Co. London, 1907

Biographical Database of Southern African Science

F.H. Barber and R. Frewen. (Edited by E.C. Tabler) Zambezia and Matabeleland in the Seventies. The Narrative of Frederick Hugh Barber 1875 and 1877-1878 and The Journal of Richard Frewen 1877-1878. Chatto and Windus for the Rhodes-Livingstone Museum London, 1960

A. Cohen. Mary Elizabeth Barber, Some early South African Geologists and the discoveries of diamonds. Earth Sciences History Vol 22, No 2, 2003

T. Hammel. Shaping Natural History and Settler Society: Mary Elizabeth Barber and the Nineteenth Century Cape. Palgrave Macmillan

I. Mitford Barberton. Barbers of the Peak; a history of the Barber, Atherstone and Bowker families. Oxford University Press, 1934. Internet Archive

https://www.1820settlers.com/genealogy/getperson

South African Biographical Dictionary. Pretoria. Humanities Research Council

E.C. Tabler. Pioneers of Rhodesia. C. Struik (Pty) Ltd. Cape Town, 1966

[i] Zambezia and Matabeleland in the Seventies, Frontispiece

[ii] Barbers of the Peak, P93

[iii] https://www.1820settlers.com states FHB was born in Grahamstown

[iv] Some early South African Geologists, P160

[v] Shaping Natural History and Settler Society, P3

[vi] Some early South African Geologists, P161

[viii] Some early South African Geologists, P162

[ix] Ibid, P162

[x] Ibid, P163

[xi] Ibid, P163

[xii] Ibid, P167

[xiii] Pioneers of Rhodesia, P77

[xiv] Ibid, P112

[xv] Pandamatenga means “the tree from where trade is done”

[xvi] Westbeech’s road between Plumtree and Pandamatenga roughly forms the border between Botswana and Zimbabwe today

[xvii] An aum being the equivalent of forty imperial gallons

[xviii] Tati had its beginnings in 1868-70 following Karl Mauch’s reports of gold. The gold rush was soon over leaving a few permanent residents in the 1770’s.

[xix] Invasion of Shoshong by the amaNdebele in 1863 was sent by Mzilikazi under the leadership of Lobengula

[xx] A wide-brimmed hat with low crown, similar to a slouch hat

[xxi] i.e. it had survived African horse-sickness

[xxii] Described by Selous in A Hunter’s Wanderings in Africa as: “About a fortnight from our start we reached Linquasi, a long narrow valley, presenting the appearance of an ancient river bed, with several fine, deep holes of water along its course, which being fed by springs, never dry up. In the south of the present-day Hwange National Park.

[xxiii] His name is not listed in E.C. Tabler’s Pioneers of Rhodesia, but in 1879 he accompanied Selous and Edwin Miller to the Chobe river

[xxiv] The house was built in 1873 by John Halyet, an ex-sailor. He also built a wagon-shed for the King at Old Bulawayo. He may have jumped ship at some time and came up to Matabeleland and was nicknamed ‘Johnny Stink’ by the amaNdebele. He built brick houses for the missionaries at Inyati as well as the Jesuits at Old Bulawayo and was still alive in 1887 with an amaNdebele wife and children.

[xxv] Zambezia and Matabeleland in the Seventies, P103

[xxvi] Ibid, P104

[xxvii] Ibid, P102

[xxviii] Ibid, P103

[xxix] Pioneers of Rhodesia, P11

[xxx] Barbers of the Peak, P104

[xxxii] Wikipedia - Barberton

[xxxiii] Barbers of the Peak, P104

[xxxiv] Biographical Database of Southern African Science

[xxxv] 1820settlers.com