Early traveller’s impressions of Gubulawayo

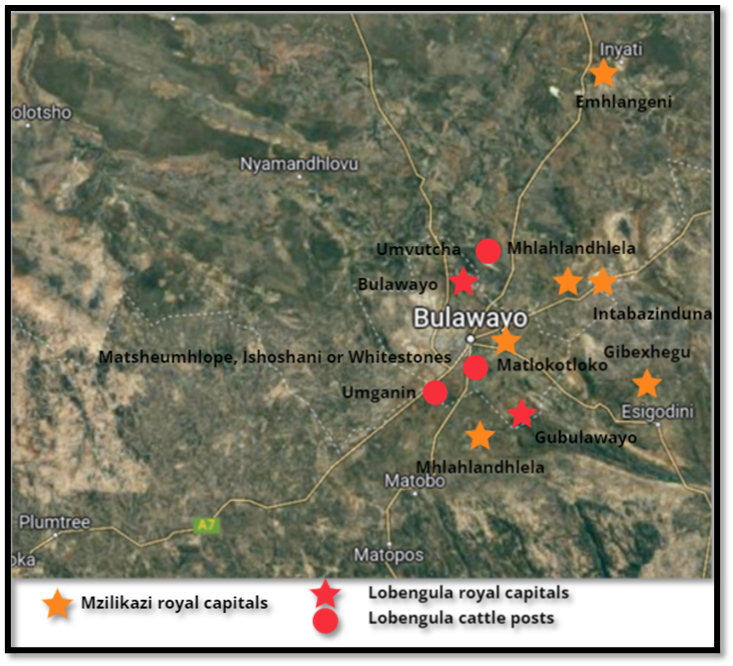

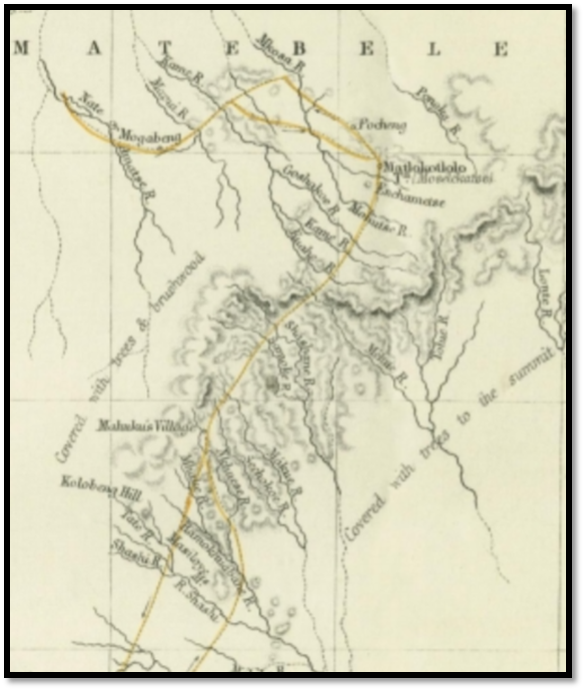

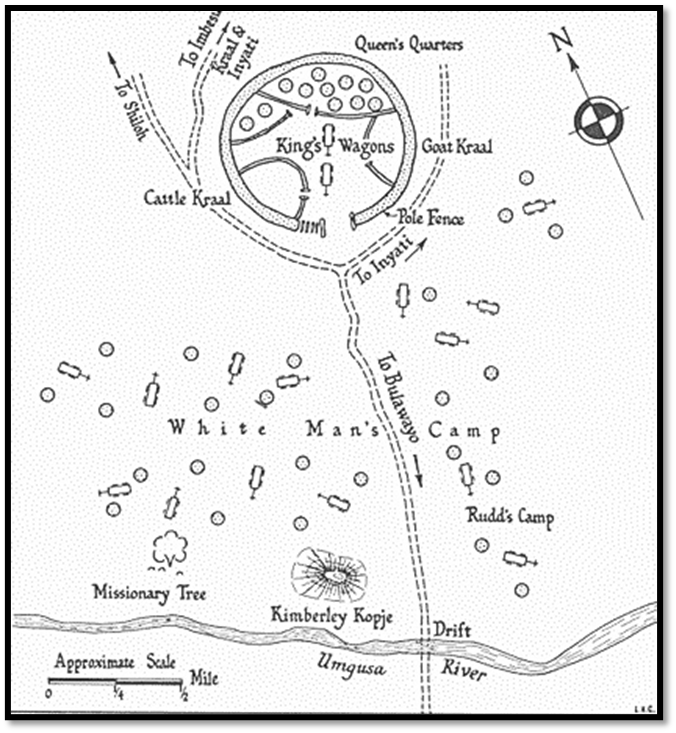

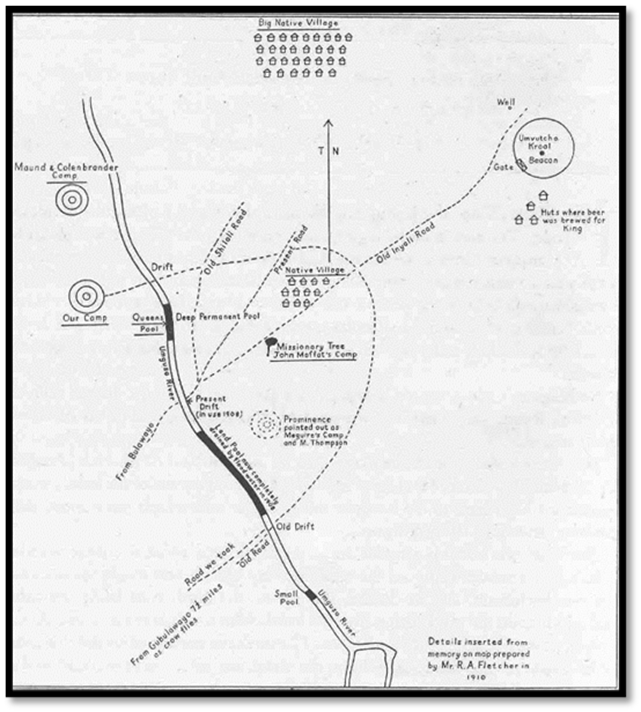

A map of the approximate positions of the amaNdebele royal kraals of Kings Mzilikazi and Lobengula in the proximity of present-day Bulawayo in Matabeleland is given below. The royal kraals often moved because surrounding cattle grazing or water and firewood had become exhausted, or when one of the Queen’s died, and the new kraal might be sited quite close or 20 km away across the watershed. Several kraals at different sites named Matlokotloko are known to have existed.[i]

A rather concise history of amaNdebele migration is given as background to their final settlement in present-day Matabeleland.

References to present-day Bulawayo and the Bulawayo in Zululand are spelt as such; the two pre-1893 royal kraals in Matabeleland are referred to as Old Gubulawayo and Gubulawayo in this article

Mzilikazi and Shaka’s Bulawayo in Zululand

The Kumalo were a small tribe led by Chief Zwide, but after Matshobana, Mzilikazi’s father, plotted to oust Zwide he was killed and Mzilikazi took his place. However he wanted to avenge his father’s death and in a battle against the Zulu, Mzilikazi and his regiment rebelled against Zwide and joined forces with the Zulu.

In 1818 Mzilikazi was 27 years old when he left Northern Natal with his people and their cattle and fled to Bulawayo,[ii] the Zulu Chief Shaka’s (or Tshaka) capital on the Mhodi stream, a tributary of the Umkumbane in the Babanago district. Oliver Ransford states this was a small kraal of approximately 100 huts,[iii] however as Shaka’s nation grew he moved to a new capital Bulawayo in the Mhlathuze district, near the present-day town of Eshowe in Kwa-Zulu Natal.[iv]

Mzilikazi proved an able warrior and was given command of a regiment recruited from his own Khumalo tribe and moved back to his ancestral homeland between the Kwebesi and Umkuza rivers, north of Bulawayo and east of the present-day town of Nongoma although he spent much time at Shaka’s capital at Bulawayo.

In 1819 Shaka moved his capital to the Umhlatuzi valley, east of Eshowe and Mzilikazi moved with him. The town was first called Gibexhegu[v] but later changed its name to Bulawayo. Both these names remained in the Kumalo’s memory for the future. One of Lobengula’s praise names was “black calf of Bulawayo”[vi]

Mzilikazi breaks away

In 1821 Mzilikazi was sent to raid cattle from the Sotho tribes to the west of the Drakensberg mountains. Militarily the raid was a great success with great numbers of cattle captured, but the success went to his head and Mzilikazi decide to keep the spoils rather than hand them over. A violent confrontation took place and Mzilikazi was forced to flee Zululand and cross the Drakensberg with his kinsmen.

Shaka sent a military expedition made up of Izimpohlo, or the Bachelors’ Brigade, comprising mostly of young men in 1822 to punish the rebellious commander. To defend themselves, Mzilikazi’s warriors, women and children moved to a strong defensive position at Entubeni hills in the upper Sikwebezi Valley with only one path to its summit. From its summit the Kumalo’s launched rocks down on the Izimpohlo who felt completely helpless until a Kumalo traitor named Zeni showed them the hidden route up the hill.

Caught by surprise the Kumalo’s suffered a disastrous defeat and Mzilikazi and three hundred warriors with women and children fled from Entubeni Hills. They fled north attacking isolated Sotho kraals gathering cattle and adding young women and males who were assimilated into their numbers. The Sotho gave them the name of the amaNdebele[vii] from the long ox-hide shields the warriors carried.[viii] Within a few years they were amongst the most feared tribes in the region with their short stabbing assegais and ox-hide shields and favoured close-quarter fighting after enveloping their opponents in the traditional Zulu horn and crescent formation.

About 1823 they reached the temporary safety of the upper Oliphants River, a tributary of the Limpopo and the traditional home of the Pedi tribe and settled in the Nzundza area at a place they called Ekuphumuleni (meaning a place of rest) and formed an alliance with the local Nguni people. However they were still within the reach of Shaka’s impi’s, the Pedi (North Sotho’s) were hostile and the area was not particularly suited to cattle rearing.

After 1825 drought forced Mzilikazi and his followers to move southwest where they settled on the Vaal River before in mid-1827 moving north to the area of present-day Pretoria on the Apies river. By 1829 they had conquered all the tribes formerly occupying the Magaliesberg mountain range as far as present-day Rustenberg. Their largest military kraal was at Kungwini situated at the foot of the Wonderboom Mountains on the Apies River, just north of present day Pretoria, another was Dinaneni, north of the Hartbeespoort Dam with a third at Hlahlandlela near Rustenberg. Mzilikazi’s military headquarters kraal was further west at Mosega. The most northern military kraal was on the Crocodile river south of its confluence with the Limpopo at Hlahlandlela where they continued with their cattle raiding into present-day Botswana.

Mzilikazi meets Robert Moffat

Mzilikazi first meet Moffat who came at Mzilikazi’s request from his mission station at Kuruman to Kungwini and began an enduring friendship between the two men. Mzilikazi called Moffat Moshete.

When Robert Moffat went to meet Mzilikazi he describes the devastation brought about by the amaNdebele and that the survivors had lost all their cattle and were surviving on game, roots and berries and lived in terror of further attacks. In the Magaliesberg region he says everything had been destroyed: “Nothing now remained but dilapidated walls, heaps of stones, and rubbish, mingled with human skulls, which, to a contemplative mind, told their ghastly tale. These are now the abodes of reptiles and beasts of prey. Occasionally a large stone-fold might be seen occupied by the cattle of the Matabele, who had caused the land thus to mourn.”

One of the survivors described their ordeal: “The clash of shields was the signal of triumph. Our people fled with their cattle to the top of yonder mount. The Matabele entered the town with the roar of the lion; they pillaged and fired the houses, speared the mothers, and cast their infants to the flames. The sun went down. The victors emerged from the smoking plain and pursued their course, surrounding the base of yonder hill. They slaughtered cattle, they danced and sang till the dawn of day; they ascended and killed till their hands were weary of the spear. Stooping to the ground on which we stood, he took up a little dust in his hand, blowing it off and holding out his naked palm, he added: ‘That is all that remains of the great chief of the blue coloured cattle.”

Moffat was taken to Mzilikazi’s capital at Kungwini, then at the place now called Kommandonek located near where the Magalies and Crocodile rivers pass through the Magaliesberg. In his journal, Moffat gives us the earliest descriptions of Mzilikazi. There was much of Mzilikazi that appealed to Moffat: "He is exceedingly affable in his manners" and "cheerfulness predominates in him." Yet Moffat was fully aware of the stark contrast between Mzilikazi's friendliness towards him and the nature of his rule writing: "He might be taken for anything but a tyrant from his appearance, but for all that, it may be truly said of him he dipped his sword in blood and wrote his name on lands and cities desolate."

Wikipedia: Mzilikazi watercolour by Captain William Cornwallis Harris, circa 1836

The amaNdebele are forced to move yet again

Chief Dingane had succeeded Shaka in 1828 and the Zulu continued to vow revenge on Mzilikazi and in September 1830 Dingane sent his army to attack Mzilikazi although they were beaten back. Mzilikazi then in turn attacked the various Tswana nations to his west and drove the various tribes either southwest toward Kuruman, west into the margins of the Kalahari Desert, or northwest into present-day Botswana. Having scattered any potential opposition in 1832 the amaNdebele moved to the headwaters of the Marico river at Mosega, 300 km northeast of Kuruman. In the Marico valley were fertile grazing lands for their cattle and the tribe now numbered about 60,000 after incorporating conquered youths and hoped to settle down.

There is an amaNdebele legend that Robert Moffat advised Mzilikazi to move north across the Limpopo river into the good cattle country of Matabeleland to avoid clashing with the Boers who in the 1830’s were trekking northwards from the Cape.

The amaNdebele get harassed and defeated

Andries Hendrik Potgieter and his party had moved north on their Great Trek to the present-day Free State, where they signed a treaty with Moroka, the leader of the Baralong that laid down that the Boers would protect the Baralong against the amaNdebele raiders in exchange for land. The Boers now found Mzilikazi and the amaNdebele a threat to their advancement into the interior.

In 1834 the amaNdebele had been attacked by a Tswana-Griqua and Kora-Griqua force but managed to hold their ground. Mzilikazi felt threatened by the Boer presence from the south which led to the amaNdebele attack on the Potgieter laager in October 1836 at Vegkop[ix] near the present-day town of Helibron.The attack was beaten off, but the Matabele made off with most of the trekker oxen, key for pulling their wagons.

The Tswana (Rolong) people assisted the voortrekkers in recovering some of their cattle, but revenge attacks were also planned. On 17 January 1837 voortrekkers under the command of Piet Retief and Gerrit Maritz destroyed the amaNdebele town of Mosega recovering about 6,000 cattle; another 15 or 16 kraals were destroyed with more than 1,000 amaNdebele warriors killed. This was followed by the Battle of Gabeni from 4–13 November 1837, led by Potgieter and Uys that led to a 9 day running fight when they destroyed most of the amaNdebele kraals along the Marico River.

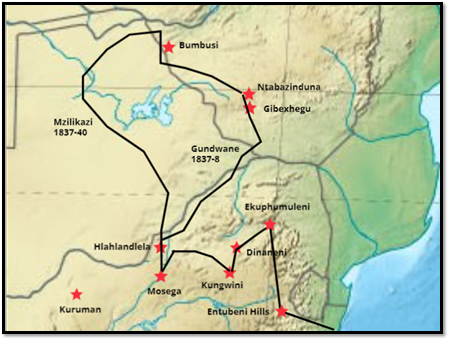

Migrations of the amaNdebele 1822-1840

The amaNdebele travel north across the Limpopo river

Mzilikazi realised that he did not have a chance against the Boer guns and mounted horsemen and decided to escape with 15,000 of his people from the Marico valley. The only hope of survival for the amaNdebele lay in flight and in 1837 Mzilikazi led his people northwards although they separated into two groups.

Gibexhegu the first capital in Matabeleland

The first group was led by Mzilikazi’s maternal Gundwane Ndiweni[x] with the amaNdebele cattle, women and children, including Mzilikazi's sons Nkulumane[xi] and Lobengula. They took a direct route crossing the Limpopo, Motloutse (formerly known as the Macloutsie) and Shashe Rivers and then headed east to follow the Umzingwane river up onto the highveld plateau. This was a much easier route and below present-day Esigodini (formerly Essexvale) they turned up the Ncema[xii] river and the western flank of the Mulungwane Hills to Entabenende Hill where they drove off the resident Karanga tribespeople. Ransford quotes an elder stating 50 years after the event: “Some of the headmen climbed the small hill called Umdanyazana to view the country around” before they settled at the spot[xiii] and built a town that was named Gibexhegu in memory of Shaka’s capital.

There they ploughed and sowed seed for the next harvest and waited for Mzilikazi’s return. Two harvests went by and nothing was heard. But there was a problem; Zulu custom required that its warriors be purified each year at the ceremony of the First Fruits or Inxwala and that could only be conducted by the King. A warrior remembered the people saying: “How can we live without the light of a fire?” After much discussion between Gundwane, his councillors and the mother of Nkulumane, Cikose Ndiweni, it was decided to install Nkulumane as heir. Then news was heard from Mzilikazi.

Google Earth map showing Mzilikazi and Lobengula’s royal capitals and cattle posts

Mzilikazi returns to Gibexhegu

The second group under Mzilikazi had taken a more westward direction into Bamangwato territory around and north of Lake Ngami and then into present-day Zambia and tried to raid the Makololo[xiv] in Balozi (the Barotse floodplain of the Zambesi river) but his reconnaissance efforts were checked and the amaNdebele were forced to withdraw. Travelling south he took revenge on the few Rozwi remaining at Bumbusi (See the article Bumbusi Ruin and Rock Engravings under Matabeleland North province on the website www.zimfieldguide.com) and marched south roughly along the later Westbeech Road (See the article George Westbeech and the road to Pandamatenga under Matabeleland North on the website www.zimfieldguide.com) turning east at the Nata river and staying for a short period at Gempo’s kraal. They followed the Gwayi (Gwaai) valley south-east to the vicinity of present-day Sawmills where they stayed long enough to grow crops of sorghum, rapoko, finger millet and maize.[xv]

Then they moved on up the Khami river to come onto the highveld plateau at Sivume near Nyamandhlovu, about 40 km from present-day Bulawayo, where Mzilikazi’s majakas built a temporary stockade. Here it is said under Ntaba Ikonya that he learned that Gundwane was about to induct Nkulumane as King and pondered his next move before summoning Gundwane and his councillors from Gibexhegu to meet him at the flat-topped hill Dombo-re-Mambo to celebrate their reunion.

Sometime in 1840 Gundwane and his councillors approached Mzilikazi at the agreed rendezvous where they were accused of disloyalty and instantly killed with knobkerries and their bodies thrown down the hills slopes. Since then the hill has been called Ntabazinduna – the ‘hill of the chiefs’ and remains to this day a cultural icon.[xvi] Gibexhegu kraal was destroyed and its people dispersed.

A new royal capital at Mhlahlandhlela

Mzilikazi set up his new capital in the shadow of the Ntabazinduna hill and named it Mhlahlandhlela[xvii] (translated as pathfinder or the end of the road) but is also referred to as Matlokotloko after the name of its amaNdebele regiment. It was situated either just to the east of the old Kumalo airfield built for the Rhodesia Air Training Group (RATG)[xviii] or on the nearby Cement golf course. It was here that Robert Moffat met Mzilikazi after his long journey from Kuruman in 1854.

AmaNdebele customs and rules and the tribute system

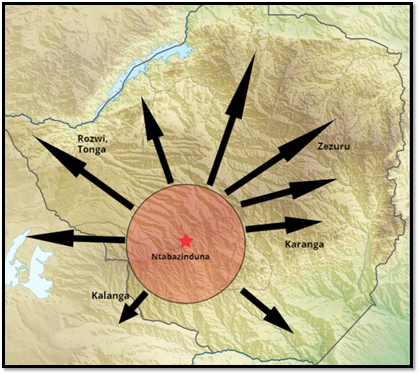

Oliver Ransford states that direct amaNdebele rule existed in a radius about 80 kms around Ntabazinduna, an area much smaller than either the Mutapa or even Rozwi states. Outside that area the amaNdebele did not seek to impose their cultural identity.[xix]

Map adapted from Bulawayo, Historic Battleground of Rhodesia showing amaNdebele settlement around Ntabazinduna and the directions of their regular raiding parties

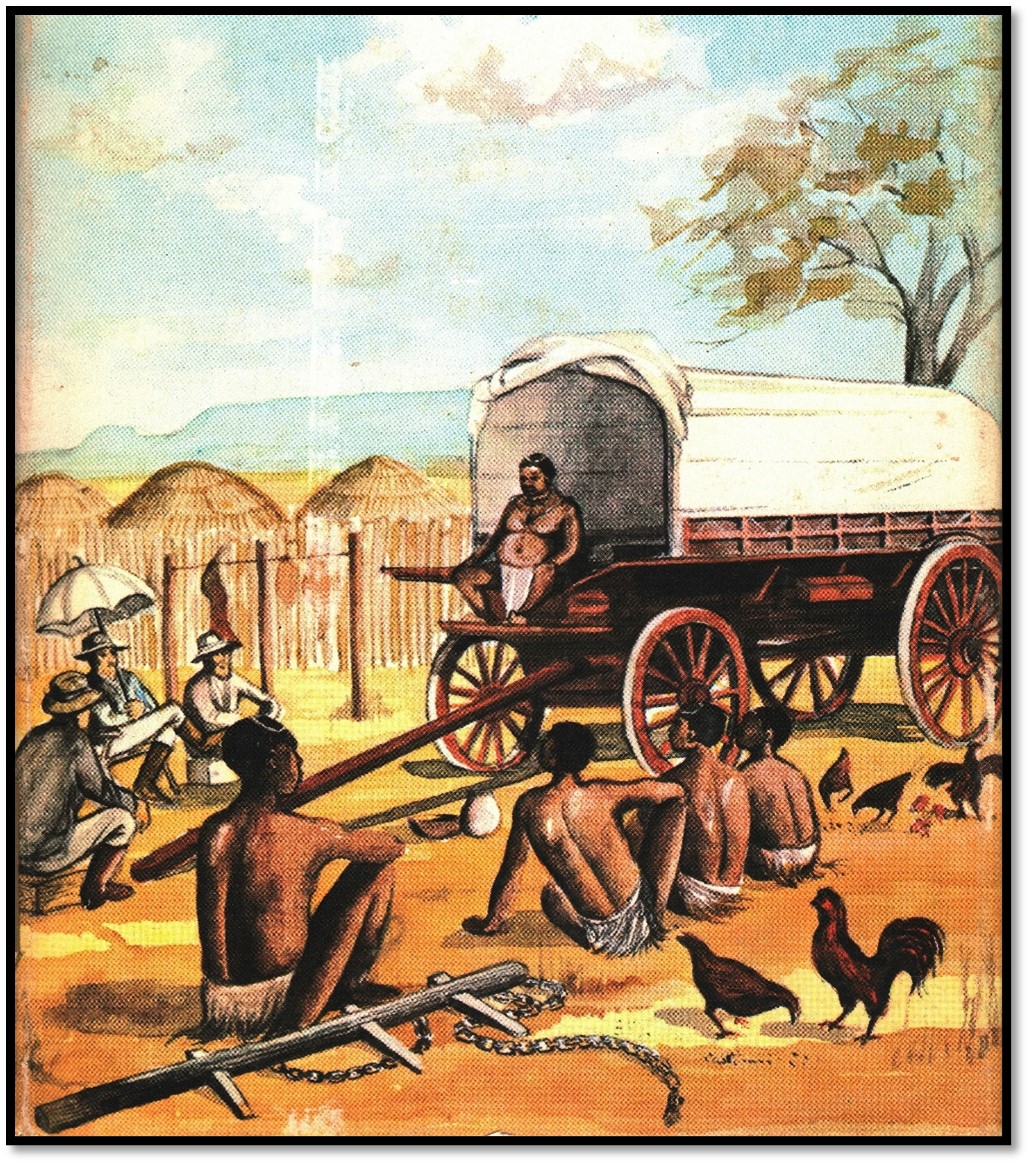

But for a much greater distance beyond the 130 km (80 miles) the surrounding tribes paid tribute and if they did not, were subject to annual incursions and harassment and assault. Each year amaNdebele impi’s raided kraals as far as the Zambesi, Mupfure (Umfuli) and Save (Sabi) rivers. They would capture cattle and grain, kill older tribespeople and bring back young boys and girls as Amahole whose members were the lowest in the amaNdebele state and initially occupied servant positions, although individuals could rise based on their performance and join a regiment as they became older.

For those that refused to pay tribute or were recalcitrant, the result was terrifying with the victims being labelled Maswina (lost ones – later corrupted to Mashona) The Rev W.A. Elliott wrote when he entered a kraal soon after it had been raided: “fastened to the ground was a row of bodies, men and women, who had been pegged down and left to the sun's scorching heat by day and the cold dews by night; left to the tender mercies of pestering flies and ravenous beasts. To add to their agonies a huge fire had been lighted against their feet and the ashes of it were still warm.”[xx]

The intended victims would be indicated during the annual Inxwala ceremony by the direction that Lobengula threw his spear. The warriors were then ‘doctored’ with dagga (cannabis) and meat cut from a living ox before moving off on their raiding activities. Many years later an old man remembered: “The next few years were very exciting, for we were always out raiding and subduing the neighbouring tribes and collecting tribute from their chiefs. If they submitted and acknowledged our King’s sovereignty and if they gave cattle freely we left them alone but if they refused, we fought them and burnt their kraals and took the young people into slavery…After we had discovered the country of the Maswina (Mashona) and their people our King partitioned it off into districts and each of our chiefs would be allocated his district in which he would collect the King’s tribute and then the raids ceased except when some Maswina chief misbehaved himself or refused to pay tribute.”[xxi]

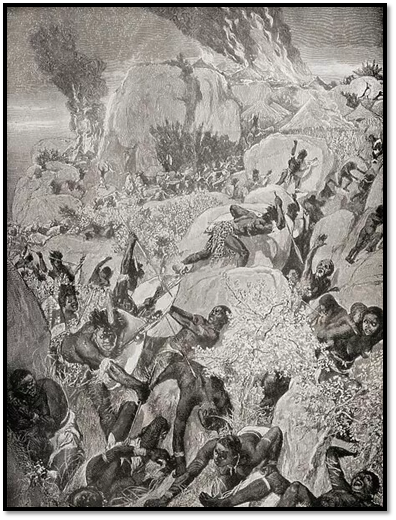

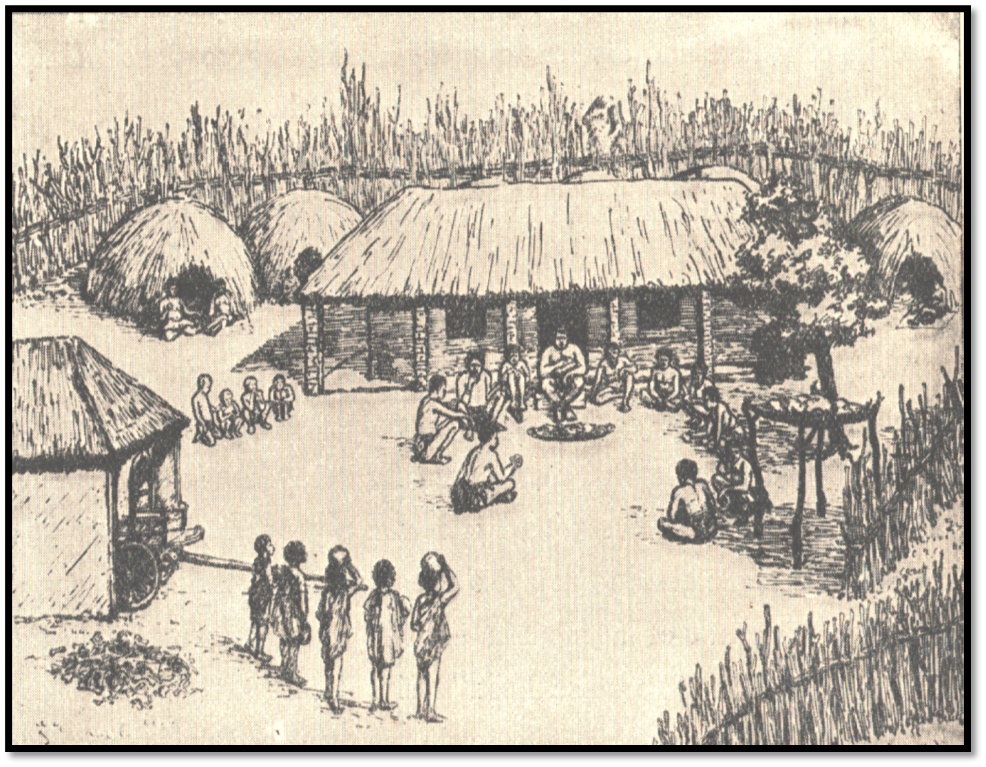

A Matabele Raid In Mashonaland from South Africa and the Transvaal War by L. Creswicke, 1900

This was confirmed in 1904 by the Tonga chief Pashu who lived in the Sebungwe area (south of present-day Lake Kariba) who stated: “while under Mzilikazi’s rule they were continually carried off, yet after Lobengula’s accession he was left unmolested so long as he paid his tribute of skins, feathers, etc, to the king.”[xxii]

Ranger writes that the evidence suggests that under Lobengula even if a chief refused to pay tribute, the punishment imposed was not necessarily arbitrary and wholesale. The well-known case of chief Lomagundi who was killed in 1891 is examined. “The chief had refused any longer to acknowledge Lobengula's supremacy or pay tax. A small impi was sent to his area; its commander first visited the senior spirit medium of the paramountcy and obtained her approval of the punishment of the chief; then the Chief’s kraal was attacked and he and his people killed. Jameson's chief reaction was one of surprise that so few people had been killed, the action, he reported was in accordance with Lobengula's laws and customs.” Ranger concludes that laws and customs of a sort, rather than random brutality, did govern amaNdebele relations with their tributaries.[xxiii]

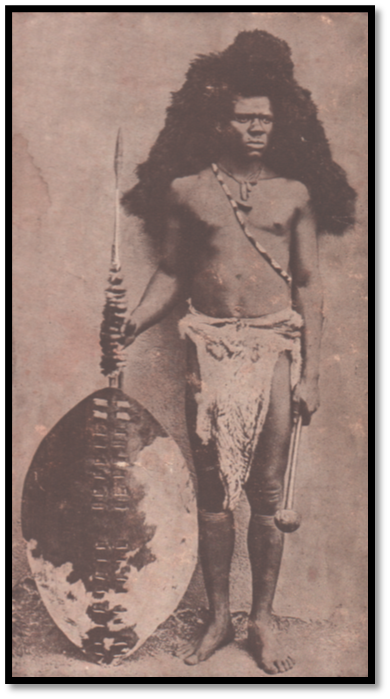

Image from Gold from the Quartz of an AmaNdebele Majaka (soldier) in full military clothing

Robert Moffat (Moshete) is the first European to visit Mzilikazi in 1854

In 1847 Mzilikazi’s old enemy Hendrik Potgieter had crossed the Limpopo and attempted to raid cattle and remove the amaNdebele from their new land, but he had been defeated by Mbigo’s Zwangendaba regiment at Ntaba Nyama (11 km south-east of Figtree) and retreated back across the Limpopo.

In 1854 Moffat began the 1,130 km trek from Kuruman to Mzilikazi’s royal capital at Mhlahlandhlela where in addition to meeting his old friend he hoped to hear news of his son-in-law, David Livingstone, who had not been heard of for over a year and to investigate the possibility of opening a new London Missionary Society (LMS) station in the amaNdebele dominions. On 4 July 1854 he recorded at the Shashe river he had: “crossed the rubicon into Moselkatse’s[xxiv] dominions” and later on the edge of the Matobo of the welcome from the amaNdebele who inspected: “my nose, my eyes and beard till they came to the conclusion that I was Moshete and no other.”[xxv]

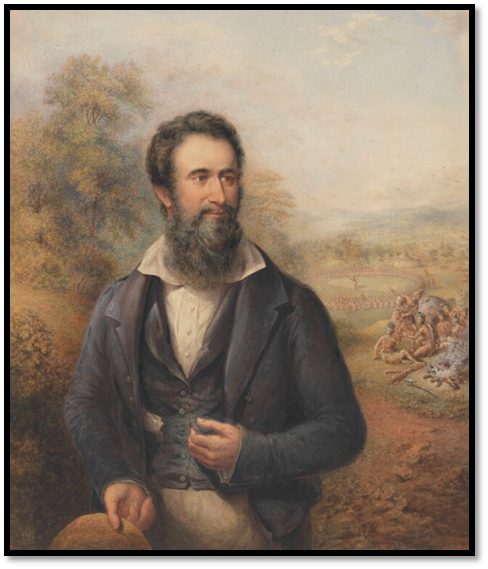

National Portrait Gallery (London NPG 6312) by George Baxter c.1842 of Robert Moffat

Robert Moffat’s second visit to the new capital at Matlokotloko in July 1856

A second Matlokotloko, Mzilikazi’s new royal capital was only partly constructed when Moffat arrived on 22 July 1856 as he notes in his journal below and he writes that they experienced some difficulty crossing the Matsheumhlope stream (called the Enchametse on the map below) and reached Matlokotloko just to the north of the present-day Harry Allen golf course in the Parklands suburb:

“July 22[xxvi] Last night after having all got fast asleep a man arrived from the town with an ox to be slaughtered. The native idea was that we must kill and eat the whole night and start on the coming morn. It was kindly intended, but not according to our way of doing things. On we went and as we passed some towns out rushed men and women to see us. It was a favourable opportunity; for no one dares come to headquarters except on special business so they made the best of the time they had. Early in the forenoon as we approached the royal residence we met men with shields and spears coming in succession to inform us of the king’s happiness at our arrival. We, as a matter of course, expected to see some such display as I had witnessed on my former visits. Being considerably in advance of the waggons we entered the large public fold and following the chief man were led to the opposite side where sat in different parties about 60 chief men.

The town appeared new, or rather half finished. There was nothing like the finish I had seen before in regal towns. We stood for a few minutes at a doorway in the fence, which seemed to lead to premises behind, where some kind of preparations were going on. While our attention was directed to the waggons Moselekatze had been moved to the entrance where we were standing. On turning round there he sat on a kaross, but how changed! The vigorous and active monarch of the Matebele, now aged, lame in the feet incapable of standing or even moving himself along the floor. I entered and he grasped my hand, gave me an impressive look, drew his mantle over his eyes and wept. Some time elapsed before he could even speak or look at me. In the meantime, Mr Edwards,[xxvii] who had gone to direct the waggons came up, little expecting to see the hero of so many battles and the conquering tyrant of so many tribes, bathed in tears which he endeavoured in vain to hide probably from some of his wives who stood behind him and his nobles who stood waiting in silence without. After some minutes spent in this way he repeated my name several times, adding: ‘Surely I'm only dreaming that you are Moffat.’ I remarked that God, whom I served, had spared us both and that I come once more to see him before I die and though very sorry to see him so ill, I was thankful to God that we were permitted to meet again. He pointed to his feet, which I had observed to be dropsical and said that they as well as other parts of his body were killing him, adding: ‘Your God has sent you to help me and heal me.

Robert Moffat’s map of his journey to Matabeleland

July 25 … Mr Edwards sent his majesty a present in the shape of a large tartan shawl, pieces of print calico, and a canister containing a large quantity of superior beads which were acknowledged with many thanks and presently afterwards they was sent to my waggon which he makes his storehouse. Can he not trust his own people?

July 26. In the evening we were rather taken by surprise to see his sable majesty walk out alone to our waggons. Medicine and regimen had done him good. He was received by subjects with shouts of congratulations.

Moffat and Mzilikazi were inseparable in the eleven weeks which followed. Together they made an attempt to reach the Zambezi river and get news of David Livingstone following the same route Mzilikazi had used fourteen years before to return to Ntabazinduna. But beyond the Nata river they entered tsetse fly country making it impossible for ox-wagons to travel any further and so after arranging for seventeen packages of provisions for Livingstone to be carried on to the Zambezi by porters they turned back to Matlokotloko.

On 9 October 1856 after a touching farewell from Mzilikazi, Moffat and Edwards left for the return trek to Kuruman escorted to Tati by a guard of honour of amaNdebele warriors.

A later royal capital Emhlangeni is at Inyati (Inyathi)

In 1857 the capital moved to Emhlangeni (amongst the reeds) but became known as Inyati from the name of the Buffalo regiment stationed nearby.

The London Missionary Society ask permission to establish a station in Mzilikazi’s country

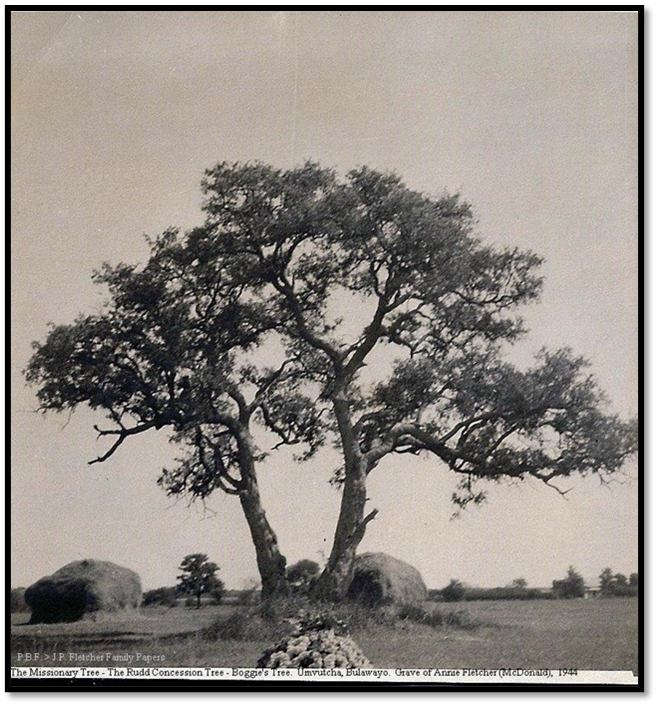

The directors of the LMS made Moffat take another journey to Matabeleland in 1857 to ask permission to introduce LMS missionaries into the country. Mzilikazi only agreed with reluctance and the party arrived in October 1859 at the Bembesi river. They were the first Europeans to settle in the Gubulawayo area and comprised Robert Moffat’s son, John Smith Moffat and his wife, Emily, William Sykes,[xxviii] a Yorkshire man in his thirties who had lost his wife on the way upcountry and Thomas Morgan Thomas.

Their timing could hardly be worse as they arrived just as Mzilikazi was preparing for the Inxwala ceremony during which amaNdebele custom ruled that it was inadvisable to meet strangers. Out of respect for Moshete he did greet the missionaries, but he ignored their request for a mission site and would disappear for days on end. They camped in the pouring rain at Ntabaikonjwa, west of Inyati at the confluence of the Bembesi and Ingwingwisi rivers for two months. Sykes wrote: “We reached Moselekatze kraal on Friday the 28th of October and his reception was not what I had expected as we were to all intents and purposes prisoners.”[xxix] Morale sank and there was talk of abandoning their mission and returning to Kuruman.

However they learnt with great joy that Mzilikazi intended to give his friend Moshete a large tract of land and on 23 December 1859 they were taken to the place chosen by him. It was close to the fountain from which rose the Umhlanyane, a tributary of the Ingwingwisi river and near the Inyati regiment kraal where Mzilikazi had his royal kraal called Emhlangeni meaning ‘amongst the reeds.’

Ransford writes that although they brought Christianity to Matabeleland they achieved little in converting the amaNdebele. At the time John Moffat wondered if there were two authentic Christian converts from the amaNdebele to show for all their labours. A Church had been built at Inyati (present-day Inyathi) by 1864 but they could only fill it by bribing their ‘parishioners’ to attend Sunday service and Sykes wrote: “at the close of almost every service that I have had at home or at the villages I have been pestered by more than three-fourths of the population for ‘tusho’[xxx] In December 1861 Sykes wrote: “this will be the third year of failure.”

However despite this, just the missionary presence in the country made white men and women familiar to the amaNdebele and eased the difficulties for the hunters, traders and prospectors who followed them. In addition they provided a respite from the wilderness and a Christian home for travellers like Thomas Baines who writes with great affection about these early missionaries and on many occasions they provided life-saving medicines and nursing too.

Mzilikazi moves his royal kraal from Emhlangeni (Inyati) to Mhlahlandhlela

When one of the queens died, Mzilikazi moved his new capital to the headwaters of the Khami river and this was also named Mhlahlandhlela. His move was a great blow to the missionaries at Inyati Mission as many of his subjects moved with him leaving the mission station with a very much depleted congregation.

Death of Mzilikazi in 1868

Ransford adds that although Mzilikazi often treated the missionaries like servants who would mend his wagons and guns, he nevertheless protected them. At the end of his life Mzilikazi was at Enxiweni oluka Kumalo a private royal kraal where the king could get retreat from the protocol and routine of public life.[xxxi] Lobengula was to do the same.

Mzilikazi died on 5 September 1868 following a long period of ill health, but his death was kept a secret by his chief councillors and some of his queens who were with him at Enxiweni oluka Kumalo. A cart was brought at nightfall and the King's body was placed in it and taken to Mhlahlandlela where on the 9 September his death was revealed to the amaNdebele nation.[xxxii]

His burial took place on 2 November 1868 at Entumbane. (See the article Mzilikazi's Grave under Matabeleland South province on the website www.zimfieldguide.com)

The interregnum before Lobengula’s appointment as King

An uneasy tension existed after Mzilikazi’s death as nobody was sure if Nkulumane was still alive. He had disappeared in 1840 when Gundwane Ndiweni and his councillors had been executed at Ntabazinduna. Most amaNdebele believed he had been strangled on Mzilikazi’s orders. The regent Ncumbata said he was ordered by Mzilikazi to kill Nkulumane, that he attacked and killed the people of the kraal, but Nkulumane was not there. He stated however that Nkulumane was killed near Ntabazinduna, or ‘hill of the chief.’ The man who took Nkulumane’s life was produced and gave evidence before the nation. Lobengula was saved by a man who hid him in the shield-house, but Mbigo the commander of the Zwangendaba regiment believed he had been sent away for safety and insisted that envoys be sent down to Natal to make enquiries.[xxxiii] See also the article The arrival of the AmaNdebele in Matabeleland and the succession of King Lobengula under Matabeleland South on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

During the interregnum Nombata (Ncumbata) acted as the amaNdebele regent and he favoured Jandu, later named Lobengula as the next king. Jandu however scented danger and determined to remain out of sight until it was proven Nkulumane was no longer alive and took refuge with the Rev T.M. Thomas at Inyati and sought advice from the Mlimo at Njelele.

In 1869 after much hesitation Jandu accepted Nombata’s offer of kingship and was tutored in the royal protocol at the old capital of Mhlahlandhlela before going to his own kraal at Tshotsho.

Lobengula’s coronation and name change from Jandu to Lobengula

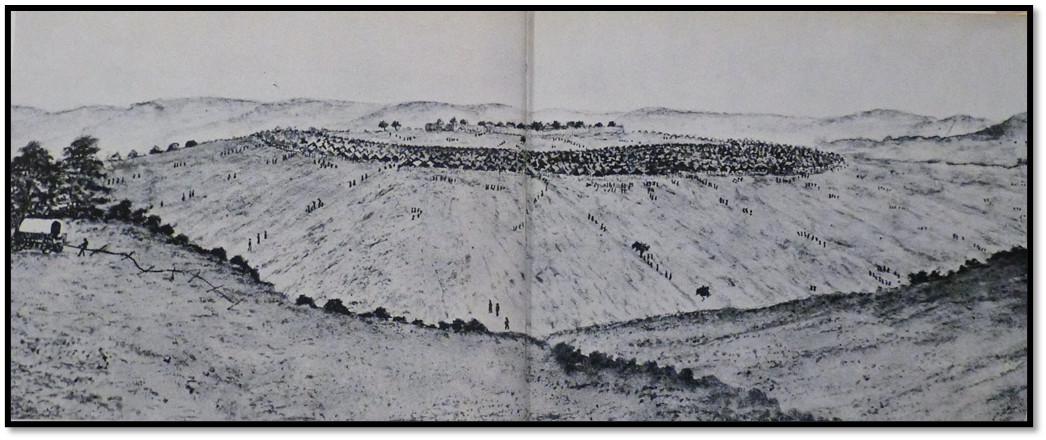

Thomas Baines wrote that an estimated between 9,000 – 10,000 people watched Lobengula installed at Mhlahlandhlela as King on 22-24 January 1870.

Rev T.M. Thomas described the event in detail on 22 January: “it was about 9 o'clock in the morning when great clouds of dust were observed ascending towards the skies about a mile to the south of Tshotsho and the approach of the mighty army soon became known to the people of the town. Now, a very great lamentation was set up by the prince's wives, children and other relatives who were present, which continued in a greater or lesser degree until the evening. The army rapidly advancing was soon near the town and passing at a quick march on the east side in a short time stood in battle array on the north about half distant. When thus situated it presented a figure of a half moon or semi-circular shape and extended about a mile from east to west.”[xxxiv]

Lobengula then mounted his horse and “led now by their prince, the six or seven thousand soldiers, in high glee, covered the country for a mile in every direction, dancing and singing the whole way from Tshotsho to Mhlahlandhlela.” At the capital a monument would be raised more than 70 years later to his father Mzilikazi.

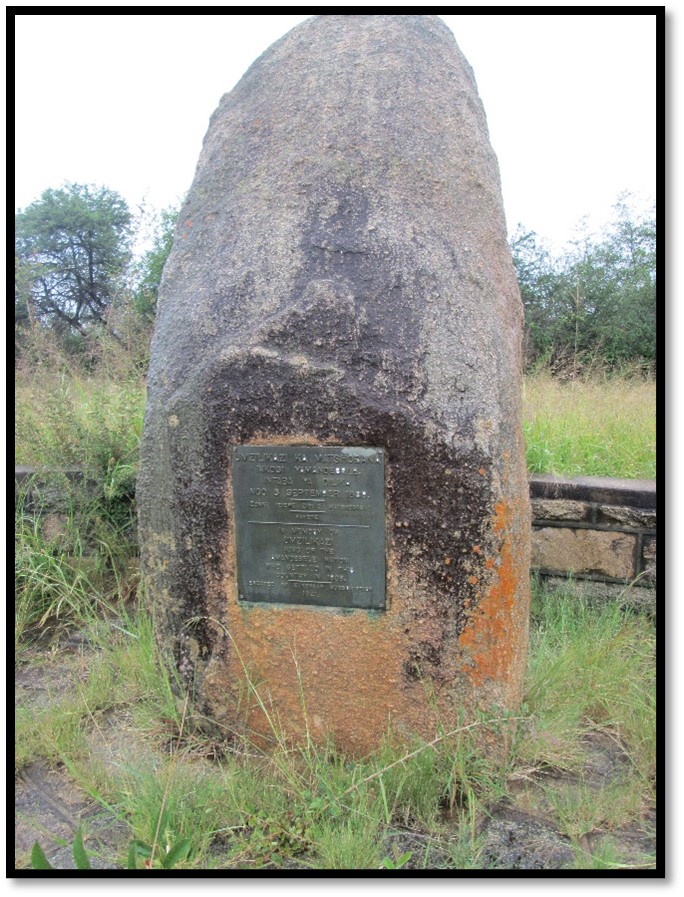

Zimbabwe National Monument No 39 to King Mzilikazi. The plaque reads: ‘In memory of Umzilikazi King of the AmaNdebele Nation who settled in this country in 1838’

See also the articles The Mzilikazi Memorial and Mzilikazi’s Grave, both under Matabeleland South on the website www.zimfieldguide.com

“An ox was brought and presented to him and by this act he was invited to enter the city which he did by the north gate. Proceeding to the goat kraal – the holy place of the Matabele, he was welcomed by an aged blind man called Umtamtjana, who acted now as the high priest of the tribe. This man, by instructions, ceremonies and charms, prepared the prince for the coronation time and purified all the huge earthen pots and wooden bowls and dishes before the approaching festivities.”[xxxv]

Thomas continues: “To a looker-on from the adjacent hillock, where I stood at the time, the view was a fine one. The motley, moving, mighty mass of people presented themselves with their black and white, red and white, speckled or other coloured oblong shields (according to their regiments) in their left hands and long staves in their right, swelling their songs of praise to their illustrious ancestors and former kings like the chanting of a great cathedral, while their feet, as they lifted them in turns from the ground, the time was kept. While thus formed, dressed and engaged, the whole multitude moved from one side to the other like the trees of a forest in a strong breeze.”

Following the battle with the Zwangendaba regiment and defeat of Mbigo, Jandu was given the praise name Lobengula, ‘the scatterer’ by which he was known for the rest of his life.

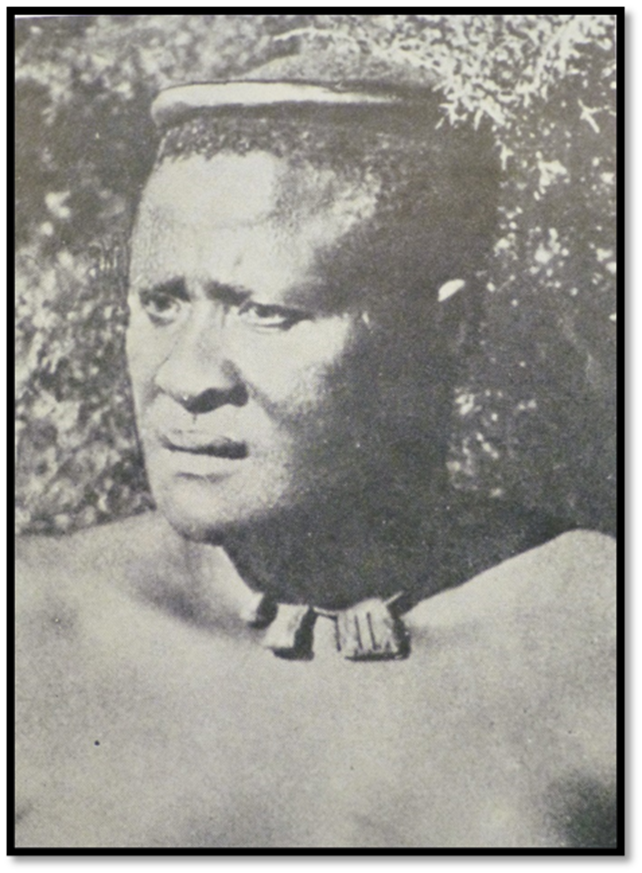

Source unknown, believed to be an image of Lobengula, King of the amaNdebele

This very rare photograph of Lobengula taken from Oliver Ransford’s book Bulawayo, Historic Battleground of Rhodesia is said to come from The Autobiography of John Hays Hammond Volume 1

A new royal town at Gubulawayo 1870 - 1881 (often called Old Bulawayo – National Monument No 116)

The second stage of the inauguration was to build a new royal town which would be the capital. The site chosen was a stony plateau about 2 miles to the east of the old capital on the southern edge of the watershed and dominated by Ntaba Inyoka (hill of the serpent) As soon as the coronation ceremony was over Lobengula made the strange decision to make the same people who 30 years before had been scattered from Gundwane’s old kraal of Gibexhegu to be the first residents of his new town. At first it was also named Gibexhegu, but after the battle with Mbigo and the Zwangendaba regiment (that took place a little south of Turk Mine, north-east of present-day Bulawayo) and as Lobengula watched the huts of the new town being built he remembered Shaka’s royal town where Mzilikazi grew up and said: “I have been injured by my people, I shall call it Bulawayo.”[xxxvi] (often referred to by early writers as Gubulawayo i.e. at Bulawayo) or by Oliver Ransford as “the place of he who has been badly treated.”[xxxvii]

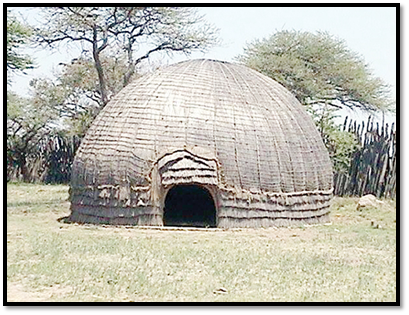

In 1968 when Oliver Ransford wrote his book there still existed the ruins of the King’s house and wagon shed as well as the indaba tree under which Lobengula held court. In 1998 a number of structures were reconstructed including a wagon shed, the outer palisade, Lobengula’s beehive huts and cattle kraal surrounded by a palisade as well as a nearby interpretive centre. They were led by a team of experts from Zululand who visited Zimbabwe to teach local craftsmen how to build beehive huts, characteristic of King Lobengula’s era. Unfortunately in August 2010, a serious bush fire swept through the site, destroying everything on the site except for the Interpretive Centre which survived unscathed. (See the article koBulawayo, or Old Bulawayo (1870 – 1881) and the Indaba Tree under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com)

Traditional bee-hive hut reconstructed at Old Gubulawayo under the supervision of Senzeni Khumalo, Curator of Archaeology at the Natural History Museum[xxxviii]

Traveller’s descriptions of Gubulawayo or Old Bulawayo

Fortunately many descriptions of the town have survived. It was surrounded by a stockade and contained about 200 huts of bee-hive type traditionally built in Zululand of arched sticks placed in a circle, a central tree trunk used as a support and split reeds and grass used to thatch the structure with a low door forcing everyone to stoop before entering the hut.

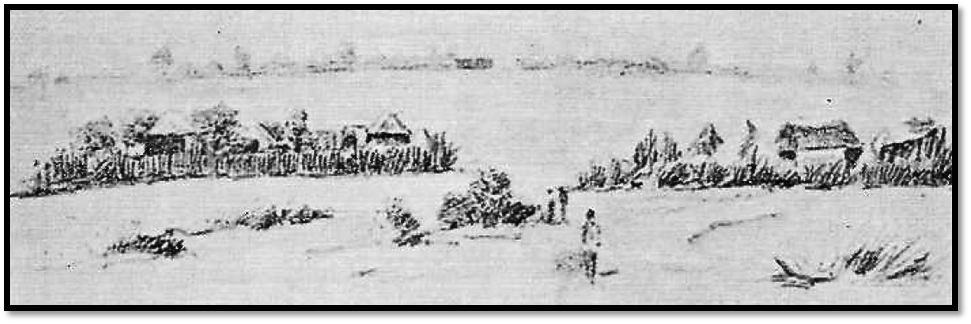

Thomas Baines in April 1870 wrote: “We crossed the Kumalo drift… and on the south eastern slope came to the town of Inthlathlangela, which we left on our right hand and came to the Umhlanyane rivulet, one of the sources, I believe, of Umtigan’s river [Mzingwane] We passed also another considerable village under a rounded hill which can be seen from Inthlathlangela and continued our course eastward, crossing other streamlets flowing south-east till we reach the new town of King No Bengula [Lobengula] situate on a slope a very little on the south side of the watershed and overlooking an extensive range of broken hill and dale with ridges running away to the south-east and rough valleys between them...”[xxxix]

Major Henry Stabb who was returning from the Victoria Falls noted on 19 July 1875: “We passed on our way the kraals of Magowain[xl] Myandin[xli] and Umhlahlanhlela (Mhlahlandhlela)[xlii] and reached Gubulawayo, 18 miles, without offsaddling… the King’s kraal is situated nearly in the centre of the town and consists of a long low thatched house of one storey high, with a verandah running the length of the building in front, built after the European style by an English trader called [Harry] Grant and a few huts of the same pattern as, but larger and more elaborately finished than the one we had slept in at Mabukutwanin[xliii] occupied by some of the King’s wives, to each of whom a separate one is appropriated and by his favourite sister[xliv] who never leaves him and whom we are told he consults in all his affairs and by other members of his household, the whole enclosed, as is the town itself by a thick hedge of cut thorn.

There are also two other enclosures adjoining, one a smaller one for his goats and horses, called the Buck kraal and another larger one for his bullocks, known as the Cattle kraal. These are guarded in the same manner as the one in which is the royal residence and at night, after the cattle, horses and goats have been collected the narrow entrances to all are closed with thornbushes by which all egress and ingress is prevented. At the entrance were huge piles of horns of oxen that had been slaughtered during the present king’s reign, place there to perpetuate his great wealth and the liberality with which he dispensed it. Dogs also swarmed in every direction and were of every description from the well-bred pointer and greyhound, the gift of some hunter, to the verist cur that ever disgraced a village.”[xlv]

Stabb writes that the king would transact the business of government under the indaba tree beside the main entrance to the Buck kraal. He had formed the idea of building a brick house two years earlier after a visit to Hope Fountain Mission where he inspected the home built for Rev Thomson by Henry Ogden and John Halyet,[xlvi] two traders with some knowledge of bricklaying.

John Halyet first built a stone wagon shed for Lobengula after which he worked in 1873 with Harry Grant in making a European-style brick house for the King although Lobengula always preferred to sleep in one of his wagons.

Artist impression of Lobengula on his wagon; from the cover of Through Matabeleland, ten months in a waggon by Col. J.G. Wood

Andrew A. Anderson in December 1877 travelling to Matabeleland: “…Sixty-three miles north of Lee’s farm is the great military station of Lo-Bengulu, situated on the summit of the watershed named Gubuluwayo or Gibbeklaik, a strong and well-laid-out town on the summit of a low hill; the king’s houses and his cattle kraal being in the centre, surrounded by strong fencing, leaving an open space, round which the town is built…From the Tati gold-fields to Gubuluwayo, the military kraal, distance 126 miles.

30 December — We crossed the Carmarlo (Kumalo) drift, and went on to one of Lo-Bengulu’s country stations, Umcarno, which is situated about twelve miles on the west of Gubuluwayo, where I found the king sitting on his waggon-box in his kraal, and the Rev. Mr Sykes and Mrs Sykes at their waggon a short distance away…”[xlvii]

“…Gubuluwayo up to recently has been the principal military kraal of Lo-Bengulu; latterly he has removed to another locality. It was on my last visit very extensive, containing several thousand people. His own residence was built similar to any English house, with a verandah, supported by posts. There were several rooms, but most of them were in dreadful disorder; boxes, elephants’ tusks, empty champagne and English beer bottles, karosses, old clothes, guns, shields, and assegai’s, all covered with dust and dirt. Elephants’ tusks strewed the verandah; there was no room to walk about or seats to sit upon. There were three other buildings, several waggons, an old cart, and rubbish everywhere. Close to the house was his principal cattle kraal, and another smaller one on the left.

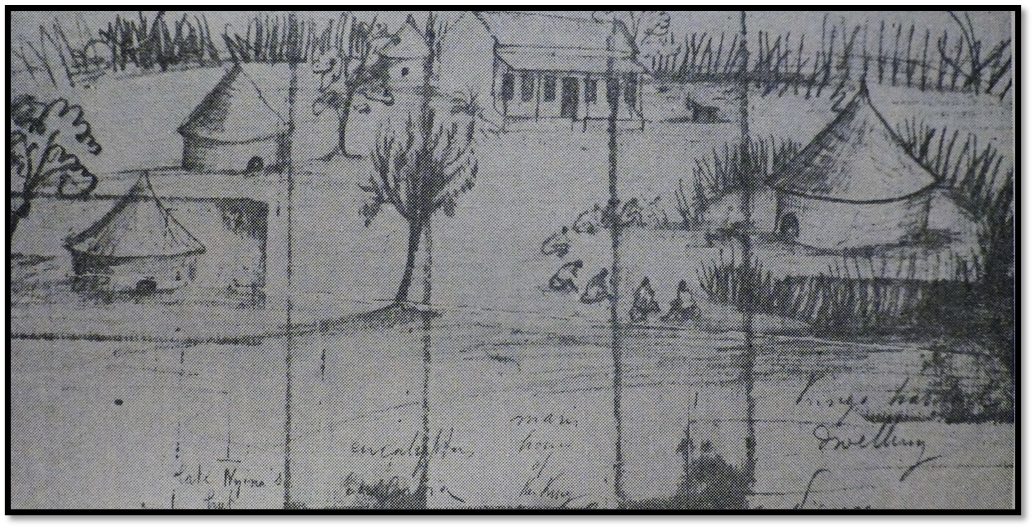

From Journey to Bulawayo – sketch by Fr Croonenberghs of Lobengula’s isigodla (isikohlo’ – royal enclosure)

The passage leading to the interior of the enclosure passed between; it is only wide enough for one to pass along at a time, and in wet weather is several inches deep in mud. This enclosure exceeded two acres in extent, enclosed by a high strong fence of poles placed double. Each cattle kraal was surrounded in the same way. Several thorn trees grow within the enclosure, under which the waggon stood. His sister Njina (Mncengence or Nina) occupied one of the houses. She was unmarried, very stout like her brother, and a good friend to all the English visiting the country. She had great influence with the king but was a great beggar at the same time. I had not been outspanned half an hour before she sent down a Matabele for some linen; I sent up six yards. She then sent for some beads, and I sent up a pound of them. She sent again for some sugar; I sent about a pound. The next day she wanted more linen to cover over some Kaffir beer she had been making for her brother; I sent her only three yards. It is the same with all who go there.

There were many traders at the station who kept stores, some in brick houses, others in huts, situated outside of the military station that surrounded the king’s kraal, leaving an open space of about 300 yards all round between the town and the king’s enclosure, where he reviews his troops on grand occasions. Several trees are growing upon it. The station commands a view in all directions. The stream from which the town is supplied with water is at the foot of the hill, about a third of a mile from the nearest huts. The country round is very bare of trees. Gardens are situated on the rising ground beyond the hill, upon which the town is built.

Corn is the principal food of the people. The women cultivate the land and bring water to their houses, so that there is a constant stream of them with their pots going up and down the hill on all sides, conveying it to their houses. Most of the women have little black babies on their backs, supported by well-worn skins of the wild animals killed by the men; with little naked urchins running by their mother’s side, hanging on to the skin worn similar to a kilt, happy as they can be, talking to their neighbours as they meet, singing with all the lightness of a happy heart. They continue to suck until five or six years old…”[xlviii]

SOAS imagehttps://digital.soas.ac.uk/AA00001570/00001/citation: Lobengula’s kraal at Gubulawayo (1877) by A.A. Anderson. The king’s residence Is at the centre surrounded by a stockade

From Bulawayo, Historic Battleground of Rhodesia: Gubulawayo (Old Bulawayo) a watercolour by A.A. Anderson 1877

Father Croonenberghs wrote on 11 January 1880: “the plateau of Gubulawayo, about 200 metres higher than the surrounding plain, might be said to resemble the famous hill of Alesia described by Caesar. It is a rough square with sides more than 1,000 metres long.[xlix] The steepness of the slope varies from one side to another: being quite steep on one side and more gentle on the other. Towards the western side of this square, the people’s huts are grouped around a huge circular space about 500 metres in diameter. Within this open space, towards the back is the ‘isikohlo’ (the palace) and the thatched huts of princess Njina and the queens. This august group of buildings is hidden behind a high surrounding palisade and against the outside of the this are the huts of Makwekwe, the steward for the capital, those of the royal guards, the madjokas (majakas) as well as the King’s cattle kraal. It is in this latter kraal or enclosure, in which the ground level has become gradually raised by the hardened dung, that the great religious ceremonies take place.”[l]

From Africa and its Exploration, as told by its Explorers: the house at Gubuluwayo built by John Halyet for Lobengula in 1873

The Europeans at Gubulawayo (Old Bulawayo)

After an enormous meal of cooked beef and beer (outualla) with Lobengula, Henry Stabb writes the following Europeans were resident at Gubulawayo. Harry Schuch, a young German trader who worked for James Fairbairn, William Horn and his wife, his partner Matthew Clarkson and employee Golden. T. Petersen, a German who formerly worked for George Phillips, H. Greite and his wife – they sold their property that became the Old Jesuit Mission for £500. Others included Alexander Deans, R. French, McKay, William Tainton, Henry Byles and Harry Grant, George Phillips and George Martin and his wife. They all traded for themselves or for Robert Taylor at Secheli’s with elephant ivory and ostrich feathers being the most important commodities.

Rev John Boden Thomson and his wife Elizabeth were at Hope Fountain Mission with John Halyet who was building a house for the Thomson’s. Rev Thomas M. Thomas had just moved from Inyati to establish a mission at Shiloh leaving the Rev William Sykes at Inyati mission.

Henry Stabb wrote in his journal: “In this wild life all social distinctions are born down and utterly obliterated and of what a strange mixture our comrades were composed. Yet, gentle and simple, rough and polished, blasphemer and missionary, bankrupt and honest trader, outlaws and bold hunters, Bohemians all. All living beyond the pale of any law, yet all recognising a certain rough yet honest law to themselves” and he concludes: “Many, many of our sleekly religious, highly civilised and respectable good people at home might with advantage take many a wholesome lesson from them.”[li]

Frederick Hugh Barber who arrived at Gubulawayo wrote: “Wishing goodbye to these friendly natives, we trekked on and reached Bulowayo (sic) the following day. The 20 May (1877) drawing up our wagon and cart alongside the trading shop of Messrs Clarkson and Goulding (trading partners) on the slope to the east of the kraal. Here were half a dozen traders, stores and houses belonging to Messrs Westbeach (George Westbeech) and (George) Phillips, (Henry) Ogden and Catonby (trading partners) (Matthew) Clarkson and Goulding (Jack Goulden) Peterson, (Alexander) Deans and others. Lobengula was at an outpost, Amatje Umlope (Matsheumhlope, Ishoshani or Whitestones or White Rocks) so we went to see his sister Xni Xni[lii] who held a small court of her own.”[liii]

He continues: ”Bulowayo (sic) the principal town of the Matibeli, though not the most populous and there were supposed to be (I was told by the traders…) about 3,000 inhabitants, probably not so many. It is a circular-shaped town situated on the apex of the smooth dome-shaped hill, sloping gently away on all sides and surrounded by hills and wooded valleys. In the vicinity all the wood and bush had been cleared for building huts, firewood and clearings for lands, etc.

Bulowayo is about 600 yards in diameter. In this centre is the isigodla, a circular stockade of long strong poles, planted and piled together vertically enclosing the King's residence, a red brick house with a veranda, built by European and the huts of his wives and concubines (…and the huts of his sister and huts for his attendants) The house is only a showplace, as he lives and sleeps in a hut. Also ,within the stockade are his milk cows and goats in their respective kraals, his wagons and huts for storing ivory and articles traded from the white man. In his house, or on the veranda was a large, cushioned horse-hair armchair in which he sat or reclined when the sun was hot, but as a rule he preferred his elevated seat on the waggon box in front of his waggon, from which elevated position he could and did look down morally and physically on his visitors.

Piled up in the corners of one room were many rifles and guns and cartridges were strewn about the floor. Among the guns were beautiful rifles by the best known London makers, rusting and getting mouldy. I asked why they did not take care of them. ‘Oh, it does not matter. Isn't he the king? Can he not buy more?’ It was a pity but it was good for trade. Round the isigodla was a round circular space dividing it from the outer circular belt of huts where the common people live. In this space the festivals, dances and savage rites are carried on.”[liv]

The Jesuits at Gubulawayo

The Jesuits arrived in 1879, Greite had opposed their arrival in favour of the LMS, but changed his tune when Fr Depelchin offered to buy his stone house and corrugated iron house that was initially used as a chapel and stable for £500. Their mission buildings were less than one kilometre from Gubulawayo and they quite soon added a chapel dedicated to the Sacred Heart that was 20 feet long and 10 feet high, with dhaka walls and thatched roof and four glassed windows. When Lobengula visited in 1880 he was greatly taken by the fourteen stations of the cross painted on the walls.

Lobengula’s other residences away from Gubulawayo (Old Bulawayo)

Lobengula liked to get away from his royal capital for some peace and quiet from daily pressures and intrigue of court life. Because of the difficulties encountered over his succession and the battle with the Zwangendaba regiment and their leader Mbigo many of the Mzilikazi appointed indunas had been replaced with younger men loyal to himself.

Barber wrote in 1877: “Within a radius of 15 or 20 miles are the King’s cattle stations where he often spends weeks of his time. As soon as he is tired of one place, he inspans his waggons, one of which was filled with ivory and moves from cattle post to cattle post, accompanied by his court and bodyguard. The cattle are divided among the posts or stations according to colour. At one station are the red, at another the black and so on. Each herd is in the charge of the induna (headman) of the town. All the cattle in the country are the King’s and no beast is killed without his permission. Every case of sickness or death is immediately reported to him and special messengers come running in hot haste to report.”[lv]

Matsheumhlope, Ishoshani or Whitestones or White Rocks

This cattle kraal was situated 9 km north of Gubulawayo and was the favourite of Lobengula’s and on the site of present-day Hillside Dams. Henry Stabb wrote: “its situation is very pretty and close to plenty of water and grass” and he described finding Lobengula one day: “sitting on a large stone on the top of a small hill overlooking his camp, but from which he afterwards came down and took his favourite position on a rock in the centre of his cattle kraal.”[lvi]

On 2 September 1879 the Jesuit Fr Depelchin wrote: “On reaching Lo Bengula’s kraal at 3 pm, we set up our tent at Ishoshani, also called Amatje Amthlopi or Amantshoni Slope, that is to say the White Rocks.”[lvii]

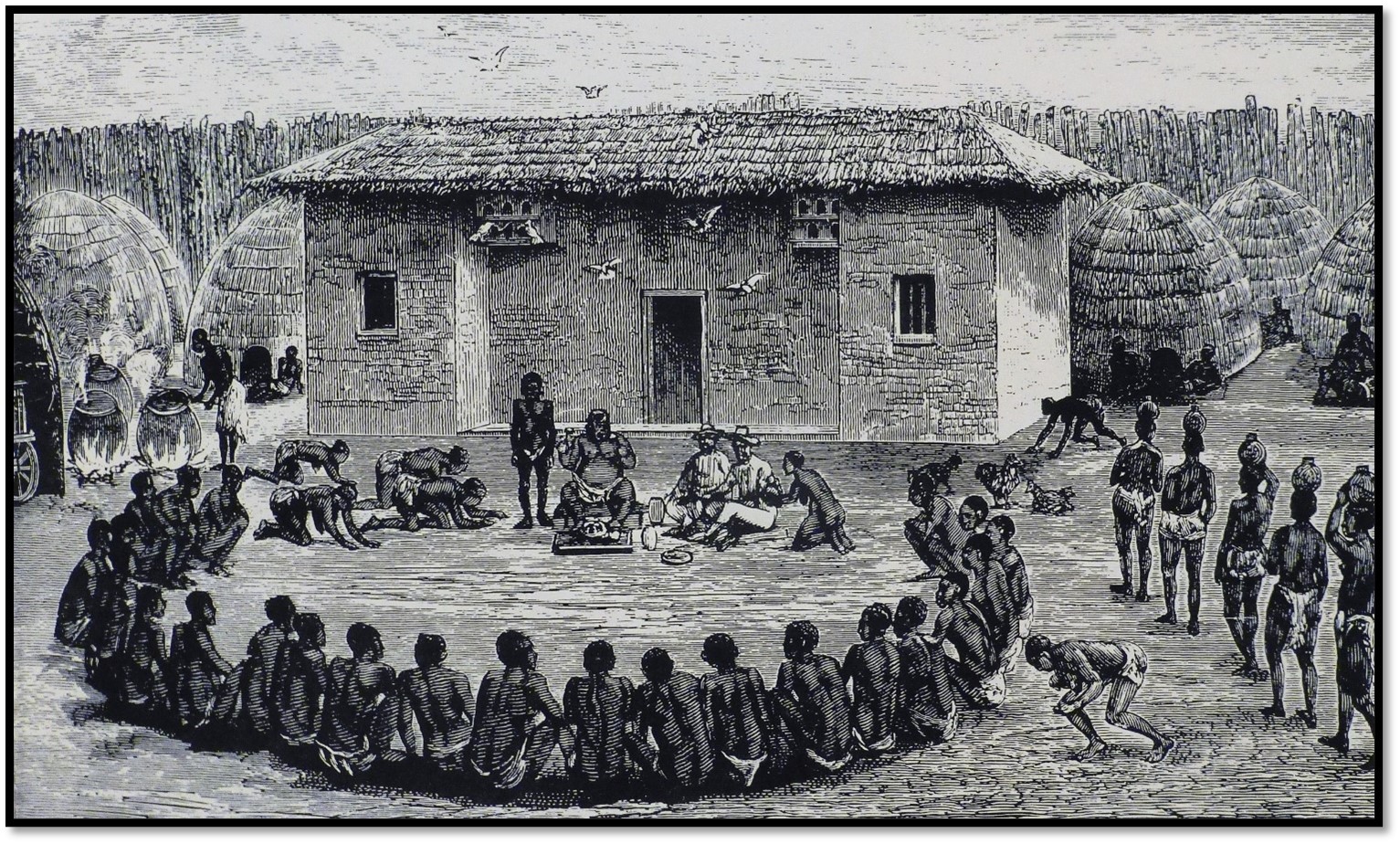

Next day with James Fairbairn interpreting they presented their gifts of a Martini rifle, a music-box, two fine blankets and trinkets. The king was busy so they returned with Fairbairn on the 5 September.

Fr Depelchin wrote of their visit: “The royal palace is like all the Matabele dwellings. These round clay huts are about 20 feet in diameter. The roof is supported by a tall pole placed in the centre. There are no windows so light can only come in through the cracks in the walls and through the door. The latter is just an opening about 80 cm high and the same in width…

We crawled into the King’s hut on our hands and knees and we took up our positions close to the entrance. His Majesty was sitting on the far side of the kotla (audience chamber) while about 10 ladies, adorned with their most brilliant trinkets, were in a circle at the opposite side of the hut. The king, seated nonchalantly on a rug, as is his custom, had in front of him the Martini rifle which we had given him as a gift and he was obviously delighted with it. He handled the weapon with great pleasure and as easily as though it were a mere feather. He is said to be an excellent shot.”[lviii]

They told Lobengula they would be happy to live as missionaries amongst his people and asked for mission stations at Gubulawayo and Tati. At first the king replied, as had Khama III, that he had enough of the ‘abafundisi’ the teachers and missionaries; that for more than 20 years the LMS missionaries had worked in his country without success. He said: “they have attained nothing, absolutely nothing; the children don’t want to learn and the grown-ups are quite happy to be as they are.“[lix]

Frederick Barber writes: “Proceeding thither, the burly potentate sitting on the top of a small rocky eminence, while below and about him, perched upon their hams, were about forty majakas (young soldiers) his bodyguard. It was evident that the king was in good humour as they were chattering and laughing and noisily discoursing. Below them in the fields, a considerable number of women and slaves were cultivating the soil with hoes. As we approached, Clarkson was noticed by him and greeted with a cheerful ‘Sakabona’ Matt and who are your friends?...

…arrived at the kraal, he climbed up on his wagon and perched himself on the front wagon box, while we found sitting places where we could, on the wagon pole and stumps of trees forming the kraal. Gradually the kraal filled with indunas, headmen and followers. Outualla (Beer) was handed round in closely woven baskets by maidens. A big vessel was handed to us, to which we did ample justice. The King’s beer was always good! Then followed a huge flat-bottomed wooden dish with a savoury joint of beef. The King cut this into chunks as big as a leg of mutton, using his left hand as a fork. A chunk was handed to us. We pulled out our pocket knives and hacked it up and ‘chawed.’ It was splendidly cooked…” [lx]

Nkantola

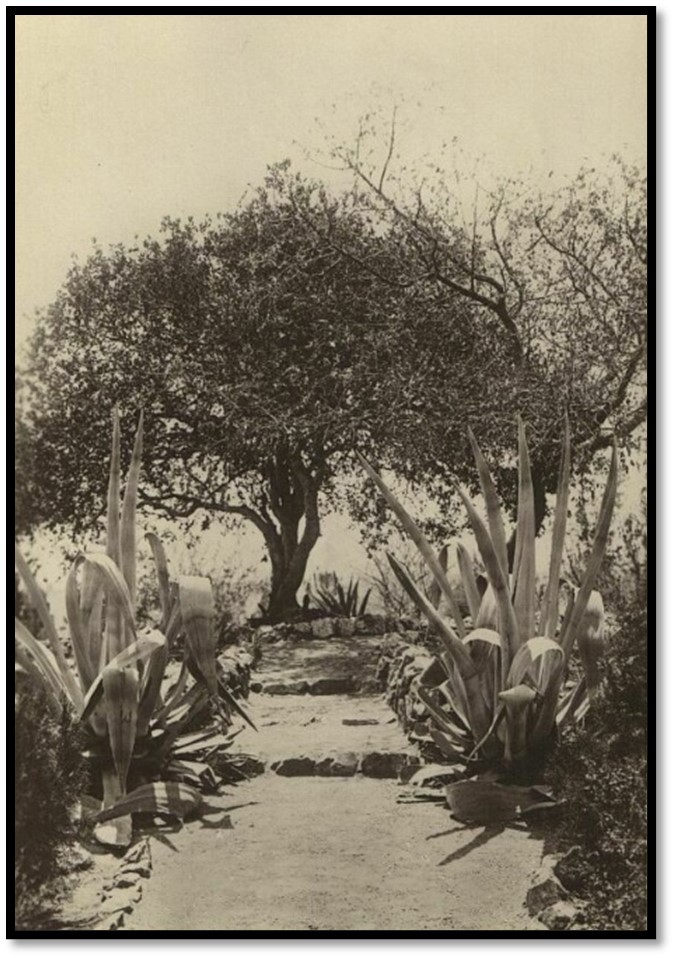

Lobengula also spent time at a small brick house that had been built for him by John Halyet at Nkantola[lxi] in the Matobo hills.

Umganin kraal

This was close to Lobengula’s old kraal before he was crowned king at Tshotsho and about 13 km north-west of Gubulawayo. On 29 April 1880 Fr Croonenberghs noted that Lobengula had left Matsheumhlope or Whitestones or White Rocks for Umganin. He speculates that perhaps the pasturage for the royal herds had become exhausted, or there were political reasons as his sister Princess Ninja had been executed by hanging on the 2 April 1880.

Father Croonenberghs writes: “…it is the custom of the Matabele kings to change their place of residence frequently and nothing could be easier to do. The thatched huts of pole and dagga (sic) which serve as homes for the king, the queens, chiefs, slaves and herds can be built in a few hours. Umganin is situated about 24 miles (39 km) from Gubulawayo, a journey of about 8 leagues on horseback.”[lxii] On 19 April 1880 Fr Croonenberghs rode with George F. Martin, a trader and Johannes C. Van Rooyen, a hunter to meet Lobengula and the Rev Charles D. Helm at Umganin where the Jesuits were given permission to stay at their house at Gubulawayo, to help the sick and to travel throughout the king’s lands.

However in May 1880 Mzilikazi said the rivers around Umganin had become infected and there was evidence the waters had been poisoned. All the men from the surrounding villages were called together and the traditional healers (n’anga) went up and down the ranks smelling out those who were guilty. Six were killed on the spot.

Barber writes that after Richard Frewen annoyed Lobengula (See the article Richard Frewen, the man who annoyed Lobengula and the consequent deaths of the Colonial government emissaries on their way to the Victoria Falls under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com) he would not give permission for them to leave Matabeleland and for a period there were no more friendly discussions with beer drinks and beef. After a profitable week at Shiloh Mission where they traded goods, muskets and lead with Rev Thomas Morgan Thomas for 4 hundredweight of ivory (203 kg) they returned to Gubulawayo and heard that Lobengula was in a better frame of mind.

Matthew Clarkson and Barber “rode over to see him at Umgawen (sic) where he was at the time. Mat, as Clarkson was called, was a great favourite of his and after a dinner of roast ox and a great deal of beer drinking the old chief’s heart softened and he told us we could go…So wishing him a not unfriendly goodbye, we returned to Bulowayo (sic) and hastened to prepare for our long journey back to Kimberley.”[lxiii]

The royal capital moves from Old Gubulawayo to a new Gubulawayo at Umhlabatine

In August 1881 Lobengula declared the grazing and firewood around Gubulawayo were exhausted and the royal capital was moving to the hill of Umhlabatine (the site of present-day State House) The Jesuits, like the LMS when Mzilikazi moved his royal capital from Inyati, were dumbfounded. Fr Croonenberghs account of the burning of Gubulawayo is related below. After much debate Lobengula requested that the Jesuits move to Old Empandeni Mission , 33 km south of Plumtree to teach the people there trade skills such as carpentry, blacksmithing and bricklaying (See appendix 3 for a description of Old Empandeni Mission in the article The Southern Column’s skirmish at the Singuesi river on 2 November 1893 revisited under Matabeleland South on the website www.zimfieldguide.com)

The LMS missionaries at Hope Fountain was similarly dismayed.

Old Gubulawayo no longer exists!

Fr Croonenberghs on 28 August 1881: “Amazing news! It will doubtless astonish you. Gubulawayo, Lo Bengula’s city, founded by him in 1870, Gubulawayo the capital of the Matabele empire and the queen of the Matoppo Hills, Gubulawayo no longer exists! Three weeks ago, Lo Bengula informed his subjects that it was his pleasure to transfer the capital to about a league beyond his residence of Amatje Amthlopi (Matsheumhlope, Ishoshani or Whitestones or White Rocks) to a place called Umhlabatine (new Gubulawayo) Gubulawayo consisted of only some 200 huts and less than 1,000 inhabitants. But during the annual festivals of the Great and Little Dances and on other ceremonial occasions, the population sometimes mounted to more than 20,000 souls. Lo Bengula has committed his goods and his arsenal to my care.

The transfer of the capital is carried out without much difficulty…These changes of capital are frequent in the black kingdoms and here is the reason why. After a few years, the kraals begin to have difficulty in subsisting due to the lack of the necessities of life, so the inhabitants have to emigrate more or less like nomads. After 10 or 12 years, all the woods near the little town have become despoiled. The trees and shrubs had been used for their fires and they have to go very far indeed to cut the daily requirements of wood for cooking. The court itself burns a great deal of wood and stocks get exhausted quickly during the festivals which last one or two weeks. Moreover, as they never manure their lands, the nearby fields become unproductive and can no longer yield even the meagre crop of millet needed for the subsistence of the inhabitants. Then they must think about moving their huts elsewhere. In making this great decision Lo Bengula indicated a district not far from one of his more usual residences. Umhlabatine is about a good league away from the White Rocks and six leagues from our house in Gubulawayo.

We do not yet know what we shall do and whether we shall follow the King to his new capital. The other white people are in a similar state of indecision about this. For them, as also for us, moving house is not an easy thing and entails great expense.”[lxiv]

Total destruction of Old Gubulawayo

Fr Croonenberghs on 20 September 1881: “I have been present at a most moving spectacle. Five days ago, on Thursday, 15 September, Gubulawayo was officially destroyed. On the seventh day after the full moon, Makwekwe, the former induna, or governor of the capital received orders from the king to go back to the old town and burn all the dwellings there which had belonged to the natives. So Makwekwe set about burning the kings palace, the queen’s huts, all the buildings in the royal kraal, sheds, coach-houses, stables and even old king, Mosilikatsi’s waggon. For a while I went round with Makwekwe on his work of destruction. Then I withdrew to a small hill to have a better view of this spectacle. When his task was finished, Makwekwe came and shook me by the hand and said ‘Lambile’ (I am hungry) He had not thought about providing himself with dinner and I had to offer him a meal at our residence of the Sacred Heart.

I fear that in a few weeks’ time the inhabitants of the neighbouring kraals will probably follow the example of the former citizens of Gubulawayo and will go off to live near the new capital. We shall then find ourselves very isolated and find it difficult to keep in contact with the Matabele nation, with their chiefs and with their king. Time will probably tell us what we have to do.”[lxv]

Fr Croonenberghs on 20 September 1881: “Gubulawayo no longer exists and we are now living in a real desert. Since the destruction of the town the Europeans spend much of their time with the king. Almost no natives at all are now to be seen in our neighbourhood. Whole weeks go by without our seeing a living soul. Three days ago Fr De Witt took Br De Sadeleer back to Tati. I hope that the health of this good and courageous Brother will stand the less healthy conditions of this station as compared with our mountain air here. Br Hedley is remaining with us. Br Nigg and I shall try to get him back on his feet and fully recovered. We must try to help him forget the terrible sufferings he endured in Umzila's country.” (See the article The 1880 journey of Rev Father Augustus Henry Law S.J. and others to Mzila’s kraal in south-eastern Zimbabwe under Manicaland on the website www.zimfieldguide.com)

Fr Croonenberghs on 18 November 1881: “Every day we are expecting to get news from the upper Zambesi. I have already mentioned Fr Depelchin’s second expedition to the banks of that great river in the empire of the Marotses (Barotses)…After Fr Depelchin’s return we shall have to think about founding another residence in Matabeleland. It is becoming impossible to remain on in Gubulawayo. For a distance of three leagues around us there is not one living soul, no kraal, no hut. It is like a desert around us and we did not come out to this country to live in isolation like a Carthusian monk.”

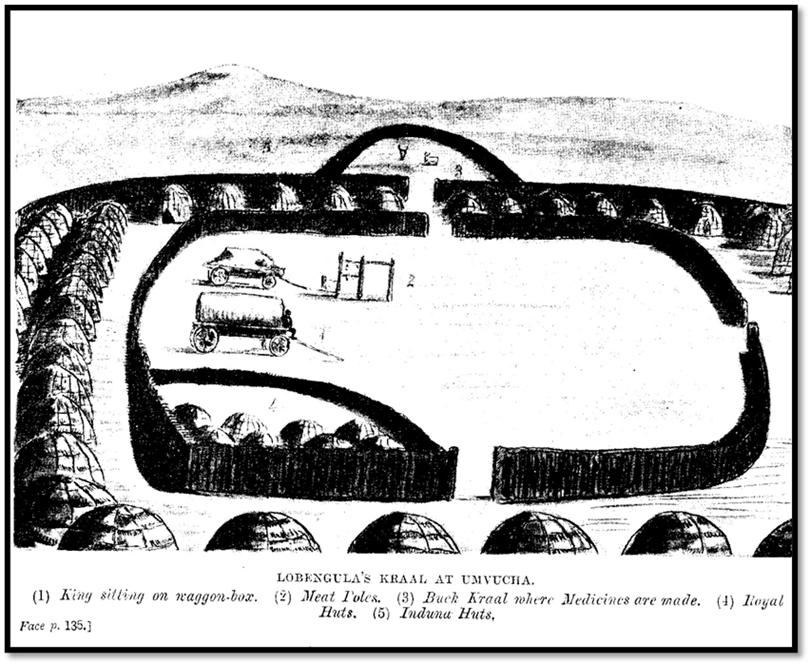

The second Gubulawayo at Umhlabatine 1881 -1893

Ransford describes the new town as follows: “The second Gubulawayo was a much grander town than the earlier capital 18 miles (22 km on Google Earth) away near Thaba Inyoka. It covered between 30 - 40 acres and was said to be a copy of Shaka’s great kraal of Bulawayo in Natal. Primarily the new Gubulawayo was a military kraal garrisoned by the Imbezu regiment which had been appointed as Lobengula’s royal bodyguard regiment, but it also had a civil population of between 15 - 20,000. The town stood on the dome shaped summit of Umhlabatine surrounded by a strong stockade of mopani poles and thornbush whose circumference was about a mile and a half. This palisade was interrupted by four gates made of poles and reeds laced tightly together and about three or four feet thick. Immediately inside stood a circle of tightly packed huts, six rows thick and of the Karanga pattern, the traditional beehive shapes now having been abandoned. The lines of huts were interspersed with occasional night kraals for goats and cattle. They looked beyond an inner barrier onto a large parade ground some 200 yards across, which surrounded the King's private quarters or isigodla. This inner sanctum consisted of a number of kraals and enclosures and the buck kraal in which the king performed various ritual duties, all contained within another mopani fence.”[lxvi]

Sketch from 'Through Matabeleland ten months in a Waggon' of the King’s royal enclosure or isigodla (isikohlo)

Ransford quotes ‘Matabele’ Wilson who wrote about Lobengula’s isigodla: “it is strongly palisaded round with a strong fence of poles from 8 - 10 feet high, the fence itself being about six feet in thickness. On the inside of this fence he had a brick house with the veranda running along the front. [lxvii]Opposite this and a little to the right is the King’s wagon house, in which he always lives, only at times going into his house during the cold weather, mostly when he needs to make a fire and sit on a chair drinking his much-loved beer. Behind the wagon house and still to the right is the wonderful goat kraal to which the king can retire, and when he does so, none of his people dare to disturb him without his permission. Here he makes rain and fixes up his medicines and takes his indunas and counsellors into private consultations. Many a poor devil has been condemned to death in that goat kraal long before he's been made aware of it himself.”

On the site of this brick house is now sited State House, formerly Government House, Bulawayo. All that remains of Gubulawayo today is the Indaba tree.

From Bulawayo, Historic Battleground of Rhodesia: Lobengula’s Indaba tree (pappea Capensis) and State House, 1897

Alexander Boggie described Lobengula’s brick house as “a long two-bedroomed brick house built with a mud floor.” Lobengula once received him seated on the throne made from a wooden crate and he says inside the king kept an untidy hoard of elephant tusks, rifles, ammunition and gold sovereigns. Many believed he also kept diamonds brought by the amaNdebele who had worked on the diamond fields at Kimberley.

Captain Edward A. Maund (then in the Bechuanaland Border Police) who visited on an official mission in 1885 wrote the following description: “The road rises and falls over frequent undulations for the next six miles up to the Umganin the soil in the hollows being very rich and produce a splendid crops of mealies. On the Umganin river the King has one of his summer residences or cattle kraals. The nature of the soil here changes to a red sandy loam and granite gives place to red sandstone. The scenery is pretty here, the banks of the brook being well wooded with acacias, mopani and mongonono trees…passing over a low range of sandstone hills you descend into the rich valley of the Umguza river. Large fields of kaffir corn wave in the valley. Its richness in quartz I have mentioned. It is, however, denuded of trees round the large kraal of Gubulawayo, which stands on an eminence overlooking the river. Gubulawayo is Lobengula’s head kraal. He has here two large houses, built for him by Europeans, beyond which are the huts of his Queens and wives, very neatly built in a court smeared with the usual cow-dung cement, which looks like asphalt. Lobengula has here a large quantity of goods stored; ivory, feathers, skins and the numerous presents of all kinds he gets from those visiting Matabeleland. These buildings are surrounded with a high palisade of mopani poles, 10 feet thick and as many high. This also encloses his buck kraal where he carries on the mysteries of ‘rainmaking’ and other rights of ‘doctoring.’ No one dare enter these sacred precincts, death being the penalty. Not knowing this, I carelessly entered to measure the dimensions and thickness of the walls. I soon found myself surrounded by a howling and gesticulating crowd, who flourished their assegais and drew their knives across their throats to indicate the fate of anyone committing such an act of sacrilege. The induna of the town came out and soon appeased the boisterous crew by saying he would himself inform the king. Beyond this is another palisade 200 yards from the former. There are no huts within this 200 yard zone. It is kept for marshalling troops and celebrating the annual dance; beyond this again, or as it were, outside the walls, all the huts of the town are built, closely packed and palisaded with branches.”[lxviii]

Unlike some of the descriptions of Shoshong that travellers described as having an awful smell about it, at Gubulawayo the sun and scavenging hyenas and jackals kept the environs ‘surprisingly healthy’ and nor were the cattle kraals inside the town unhygienic as their dung, comprised of grass, was odourless and soon dried out and was churned up at night by their feet, meant the fly nuisance was not particularly bad.

From Gold from the Quartz: Lobengula’s isigodla (isikohlo’ – royal enclosure) with the thatched huts of the Queens behind and the wagon shed on the left, the Indaba tree on the right

John Cooper-Chadwick along with Benjamin Wilson and Alexander Boggie[lxix] arrived at Gubulawayo on 12 August 1888 hoping their party would get a gold concession from Lobengula in Mashonaland. They did not get the concession although this does not seem to have stopped them assisting the three members of Cecil Rhodes’ negotiating team - Charles Rudd, Francis ‘Matabele’ Thompson and James Rochfort Maguire. Cooper-Chadwick writes: “I may mention here that our party were the only ones in the country who, from the very first, assisted Rhodes representatives in every possible way.”

He describes meeting Lobengula as follows: “Soon after arriving in Gubulawayo we went to pay our respects. and first visit to Lobengula, accompanied by Mr Mandy, who acted as interpreter. The king was seated outside the royal quarters surrounded by a large number of indunas and warriors and evidently listening to some important case…After waiting a little time, the king beckoned us to approach, which we did, giving the usual salute ‘Kumalo’ (royalty) which white men are supposed to shout when they see him and we were greeted in return by ‘Sakabona makewa’ (Good morning, white men) The king then chatted pleasantly for a time and asked various questions about our journey and said he was glad to see us. Presently, at a sign from the king, one of the slave girls brought an enormous can of outchualla (native beer) holding about a good-sized bucket full and placed it before us. The girl then knelt down and took a good drink to show there was no poison in it and this I afterwards found was always done. We again yelled out ‘Kumalo’ as thanks to the king… We then presented the king with a new sporting rifle and a case of champagne, for which he has a weakness and I also gave him the long crane feathers and letter sent by Mr Wisbeach (George Westbeech) Lobengula thanked us for these, but he takes all presents as a matter of course, as every white man entering the country and he has a large and valuable collection of costly presents, which are for the most part neglected and allowed to rust and be destroyed by white ants.”

He continues: “Our camp was situated about a mile from the town and we soon had a strong thorn fence round it which was necessary to keep out the people who crowded round begging for tusas (toosah)and bringing things for sale.

Gubulawayo is similar to all other large military kraals in the country. The town occupies a circular space about a mile in circumference. Running outside is a high and substantial palisade, inside of which the huts are built and in front of them are strong wooden stockades where the cattle are kept at night. The large inside space is used as a parade ground or for public meetings and in the centre are situated the royal quarters. Here is another well-built palisade enclosing the cattle kraal and the sacred goat kraal, which is considered the Holy of Holies, which no one can enter accept without special permission from the king and where he occasionally retires to get away from his people.

Round the walls of the enclosed courtyard are always seated a number of soldiers, messengers and slaves when the king is at home and near the entrance are two large heaps of horns from the bullocks that have been killed from time to time. There is also an inner enclosure, where the King's private huts are, in these the queens live when they come to visit him. All the large kraals are made on this principle, except that at Gubulawayo there is a waggon shed and also a well-built brick house that was made for the king by an old sailor named Halyet and meant for a royal residence, but the king seldom occupies it and prefers to live in his waggon. Inside this house, the walls are decorated with various prints and paintings, including the large sized oil painting of the Queen in a handsome frame and he always speaks of the Great White Queen with the greatest reverence and respect. The king has a large pack of dogs of various kinds, but as they are fed solely on meat, present rather a mangy appearance; he has also tame ostriches, peacocks and pigeons.

There were very few whites in the country at this time besides the missionaries and the two resident traders, Fairbairn and Peterson, who lived far apart and owned comfortable residences…”[lxx]

“…After remaining a few weeks at Gubulawayo the king visited the Imbizo kraal some 20 miles away, where we followed him. He seldom remains long in one place but travels about in his waggon to the different towns followed by his bodyguard and a large contingent of queens, indunas and members of the royal family. Strangers visiting the country are expected to follow him and usually do so though it is not compulsory and they can remain at Gubulawayo which is the white man's town. No one knows when the king intends to trek, or where he's going to; he orders the bullocks to be inspanned at a moment's notice and the people follow his waggon wheels…”[lxxi]

Lobengula’s Indaba tree at the second Gubulawayo at Umhlabatine from a 1920’s postcard

The last of the travellers to be quoted is Lieut-Col H. Vaughn-Williams who arrived at the King’s kraal on 4 August 1889, three months after leaving Kimberley with his brother Arthur and Balane. He writes that he was as: “astonished at the size of the kraal, which we could only partly see behind the fenced palisades. We outspanned near the gates in the shelter of two big trees. It was a horrid, blustery, windy day, with dust flying about everywhere. Not far from our camp was a small house and a store that belonged to Jimmy (James) Dawson who had traded there for some time and was said to have a good deal of influence with Lobengula, not always for the best. No other house was to be seen. This kraal, Gubulawayo as it was always called then, must have been more than half a mile in diameter and was said to have 15,000 or 20,000 inhabitants. It was entirely surrounded by a palisade or fence with four big gates all made of poles and reeds laced tightly together and about three or four feet thick.

Very few of the natives took any interest in us at first, so we had a quiet evening, enjoyed our supper in peace and went to bed early. Soon after we turned in (Balane and I, as usual, sleeping by the fire) two or three intombis, as the maids were called, turned up and tried to get into bed with us. One of them attempted to creep in under my kaross. They were very persistent and seemed insulted when we cleared them off. They were quite young, only about fourteen year old…

The next morning we went inside the kraal and wandered around. They were a great number of neatly made huts, well thatched, five or six rows of them all round the perimeter. There was a large open space in the middle where Lobengula and is witch doctors held their big dances in the summer. He had a small, squarely built two-roomed house, standing by itself on the edge of this space and adjoining it was the famous goats’ kraal, where indabas (as conferences are called) are held and many men and even women were done to death or sentence to be executed. In front of the house was a big fig tree, known as the Indaba Tree. Lobengula did not live in Gubulawayo except for a while in the summer; he spent most of his time at what was known as the King’s Kraal, some 7 miles north, with his favourite wives.

In his house[lxxii] at Gubulawayo the king hoarded his treasure, consisting of a number of fine tusks of ivory, rifles, ammunition given to him by white travellers, golden sovereigns from the same source and from Rhodes’ Company and it was said, diamonds, which I did not see. The latter were supposed to have been brought up by workers from the Kimberley mines and presented to the King. The house was broken down in the 1893 Matabele War, but I was told that the pantry of the house of the Governor General for Southern Rhodesia is actually built on its old site (present-day Senate House)

Most of the natives were friendly, except the young soldiers or majakas, who were always cheeky and arrogant. Jimmy Dawson, like others, warned us that if we continued with our expedition we were taking our lives in our hands, as the young men of the country were very much up against white people and were afraid that we would want to take their country. This did happen eventually, of course, four years later…

Lobengula lived at the King’s Kraal, some 7 miles away as the crow flies, north of Gubulawayo on the Umgusa River and it was called the Umvutcha Kraal. It was always known in those days as the ‘King’s kraal’ and was his favourite residents for most of the year. He never moved from there while I was in Matabeleland.”[lxxiii]

The Europeans at Gubulawayo in the 1880’s

Lobengula allocated an area on the southern bank of the Amajoda stream (now Bulawayo spruit) just one kilometre from his royal capital for the Europeans that became known as “White Man’s Camp.”[lxxiv]

Some of the traders that moved from Old Gubulawayo to the second Gubulawayo were permanently resident. They included James Dawson and his brother who built a brick store house with a corrugated iron roof that was still standing in 1968, James Fairbairn who built a house he called ‘New Valhalla’ and Johann Colenbrander. Rev James Smith Moffat initially lived in a tent that was replaced by a pole and dhaka hut. Captain Ferguson in 1890 described many of the huts as being “surrounded by ring fences of thorny mimosa bush.” However the majority of Europeans were there temporarily as hunters seeking permission to enter Mashonaland or the Zambesi Valley, prospectors and concessionaires who came requesting permission to look for gold and lived in their wagons. (See the article The Wood-Chapman-Francis syndicate of concession seekers under Bulawayo on the website www.zimfieldguide.com)

The largest camp belonged to the British South Africa Company housing Charles Rudd and his companions; nearby was the Bechuanaland Exploration Company under E. A. Maund with another belonging to Edward Renny-Tailyour.

NAZ: Dawson’s Camp sketch by Marie Lippert, 27 October 1891